Contents>> Vol. 8, No. 2

An Ethnography of Pantaron Manobo Tattooing (Pangotoeb): Towards a Heuristic Schema in Understanding Manobo Indigenous Tattoos

Andrea Malaya M. Ragragio* and Myfel D. Paluga*

* Department of Social Sciences, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of the Philippines-Mindanao, Barangay Mintal, Davao City, Philippines; Institute of Cultural Anthropology and Development Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Leiden University, Wassenaarseweg 52, 2333 AK Leiden, Netherlands

Corresponding author (Ragragio)’s e-mail: amragragio[at]up.edu.ph

DOI: 10.20495/seas.8.2_259

Pangotoeb refers to the traditional tattooing among the Pantaron Manobo of Mindanao, a practice that has not been given a systematic description and analysis before in Philippine or Mindanao studies. After giving a review of early historical and recent reports on this practice, this article provides an ethnographic description of Pantaron Manobo tattooing on the following aspects: (a) the tattoo practitioner (and her socio-symbolic contexts); (b) tools and techniques; (c) variations in body placements; (d) basic designs; and (e) the given reasons why present-day Manobo tattoo themselves. In terms of Philippine tattooing technique, this study highlights the importance of distinguishing three modal hand movements: hand-tapping, handpoking, and incising techniques; this last is unique to Mindanao relative to the rest of the Philippines and perhaps Southeast Asia. This paper also opens a comparative and exploratory cognitive approach in studying Manobo tattooing practice. Calling for a methodological declustering of the study of tattooing from its frequent association with male/warrior identity, this article concludes by selecting a limited set of figures that appears to be an enduring schema underlying Manobo tattooing practice: (a) the central role of the female gender; (b) the unique importance of the navel/abdomen as a tattooing region of the (female) body; and (c) the importance of the “ridge-pole” (and the “house” in general) in naming tattoo figures and attributing significances. These appear to be more resonant with many other aspects of Manobo culture to warrant giving this schema a heuristic value for future studies.

Keywords: tattoo, Manobo, Pantaron, Mindanao, Philippines, indigenous peoples, gender, cognitive schema

I Introduction

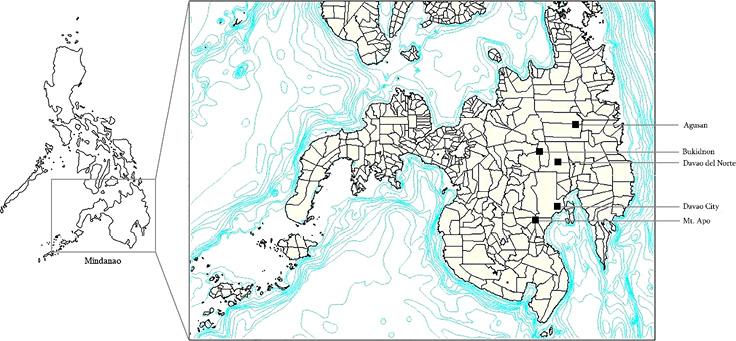

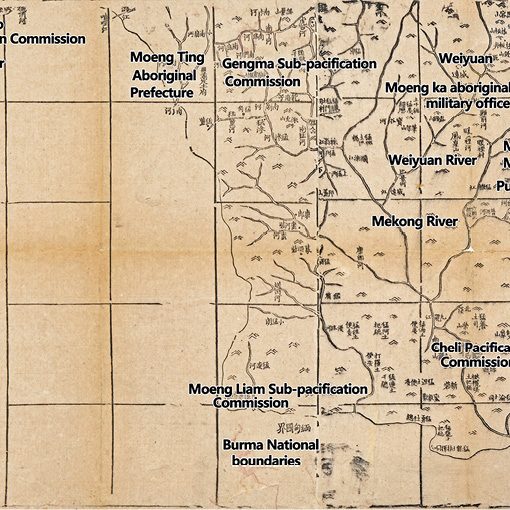

A systematic anthropological documentation of the pangotoeb, the indigenous tattoo practice of the Manobo from the Pantaron highlands (Fig. 1) of southern Mindanao, Philippines, is yet to be done. The present paper is a contribution towards this direction. It reviews the available historical accounts of the tattoo, from the earliest available records dating to the late nineteenth century, up to more recent documentation in ethnographies and visual media. The article will also present firsthand ethnographic data from interviews and observations regarding the present tattooing practice of the Manobo along the Talomo River and Simong River in Talaingod town, Davao del Norte Province, and the Salug River in San Fernando town, Bukidnon province. The data this article presents include what the designs of the tattoos are and their meanings, where they are placed on the body, and what reasons the Manobo give for their tattooing. Interviews with tattoo practitioners1) also reveal that the Pantaron Manobo tattooing technique of incising is unique from the other indigenous tattooing techniques in the Philippines, and perhaps Southeast Asia.

Fig. 1 The Pantaron Highlands

The initial aim of this research was to fill in a gap in the ethnographic description of indigenous tattooing practices in Mindanao. Unlike the tattooing practice of various groups in the Cordilleras of northern Luzon (e.g. Salvador-Amores 2013; 2002; Wilcken 2010), Mindanao tattooing has not yet been the focus of a systematic ethnographic study. In the course of developing this ethnographic description, the study evolved further interpretive directions. Meaningful connections between the tattoos and other daily objects that link them to other aspects of Manobo life began to emerge from the interviews and observations. It is this network of associations that the final section of this paper explores, forwarding them to be local “systems of representation” (Geirnaert-Martin 1992, xxviii), or “metaphors for living” (Fox 1980, 333) that may be used to describe or make sense of tattooing’s place in Pantaron Manobo society. This direction is similar to what Schildkrout (2004, 328) would describe as a “Levi-Straussian” perspective which saw body art as “a microcosm of society” that represented ideas of spirituality, social status, hierarchy and leadership, and gender and kinship relations.

Godelier (2018, 479–484), in his recent comprehensive assessment of Levi-Strauss’s structural approach still emphasized the value of analysis guided by the Levi-Straussian keywords of “structure” and “transformations,” and reiterated the continuing importance of pursuing inquiries about enduring “cognitive schemas” for the present twenty-first century social science agenda. Departing from classical structuralism, this research has been open to closely listening to local, subjective views, and paid attention to what focal images surfaced in discussions of Manobo tattooing, and how they resonate with other domains of activities. In presenting a heuristic model that may guide further studies, this paper also follows Mosko’s (2009 [1985], 1; cf., Salazar 1968) suggestion to continually explore the “analytical validity of indigenous categories” while remaining aware of the dynamism of the Pantaron Manobo as a group affected by current global economic and political forces.

I-1 Collecting Manobo Tattooing Information

The ethnographic data presented here was collected in the period between 2007 and 2015. Prior to 2013, only initial observations about the tattooing were done as these were field visits that were not centered on investigating tattooing. Data was more systematically collected from 2013 until 2015 through directed interviews with pangotoeb practitioners, recipients, and other knowledgeable persons in the community, such as elders, leaders, and epic chanters. The main field site of the study were the villages located along the Talomo River (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 for location maps), but visits and interviews were also conducted in villages on the Salug and Simong Rivers. During interviews, the same set of questions were asked in order to triangulate the replies of each interviewee. Interviews began with asking the interviewee for basic biographical details (age, if it is known, village of birth, village of residence, names and places of birth of lineal relatives including ascending generations, if they could still be remembered). Tattoo practitioners were asked to describe the process of tattooing, what items are used, and what behavioral or bodily observances must be done throughout the process. Tattoo practitioners and other tattooed persons were also asked to recall their own experiences of getting tattooed, or seeing others get tattooed.

Fig. 2 Mindanao Areas Mentioned in This Paper

Fig. 3 Talomo and Simong Rivers of Davao del Norte

Photographs of tattoos were also taken during these occasions, with the consent of, and utmost consideration for, the individuals involved. However, the actual process of tattooing was not witnessed by the researchers for no such opportunity presented itself during the intermittent field visits between 2013 and 2015, and the researchers deemed it improper to instigate a tattooing session at their behest. There was, however, two occasions in which the tattoo practitioners spontaneously offered to simulate the tattooing technique using the underside of a cassava peel. This allowed us to observe the hand movements of the practitioners and more closely examine the marks that the technique makes.

Photo elicitation was used in order to identify the names of the tattoo designs. The researchers showed the interviewees photos of tattooed persons and close-ups of his or her tattoos, and asked them if individual motifs or groups of motifs had names. This was an effective approach in identifying designs as many Pantaron Manobo are unused with using a pen and paper to draw designs. Additionally, during interviews it was not always the case that there were tattooed persons present whose tattoos may voluntarily be used as a reference when talking about designs and their names. The photos used were photos that were taken by the researchers during initial visits and interactions in the area beginning in 2007. The persons pictured were therefore those who were still living in the Pantaron area, and the interviewees were frequently acquainted with or related to the persons in the photo. This ensured that the photos used were as well-embedded in the social context of the study area as possible (Banks 2007, 60), since the objective of photo elicitation was primarily to identify the names of the designs, and not to elicit other comments (Rose 2012; Banks 2007).

These qualitative accounts are supplemented by quantitative data collected in 2014 when, in the month of April, Pantaron Manobo from Talaingod town evacuated to Davao City in the midst of counter-insurgency operations in their area. Working with the village leaders and the evacuation center secretariat committee, 90 families (or 15 families from each of the six villages located along the Talomo River) with a total of 2392) individuals were randomly selected and surveyed in order to glean a socio-demographic picture of the Manobo pangotoeb.

II Locating and Naming the Tattooing Groups: “Ata” or Pantaron Manobo?

In the formal literature (anthropological, historical, and linguistics), the Pantaron Manobo are broadly identified as “Ata Manobo” or simply “Ata.” Frank Lebar (1975, 63, as contributed by Aram Yengoyen) has given the most authoritative anthropological account (outside of linguistics) of the “Ata” in his three-volume summing-up work on the “ethnic groups” of Southeast Asia under the Human Relations Area Files. However, compared to other entries about other indigenous groups in Mindanao, the “Ata” is given the shortest space (half a page) and thus the briefest discussion in this work.

Up to this time, little progress has been made in the representation of this “Ata” group in both the scholarly literature and in popular view, even with additional research from Gloria and Magpayo (1997), Bajo (2004), and Tiu (2005). Tiu (2005) attempted to deepen this inquiry further by posing what he called the “Ata puzzle” to problematize this naming and classification of a group of people (Tiu 2005, 47–116).

The present use of the term “Ata” is complicated by its being interchangeably used with a separate category “Agta” that is more commonly understood to refer to Negrito groups on the separate island of Luzon. Such a usage has historical roots (beginning with Jesuit records in the latter half of the nineteenth century), and has been inherited by succeeding writers and documenters, and used with varying degrees of circumspection.

From the perspective of groups encompassed by this study (who are often included under the label “Ata Manobo” or “Ata”), “Manobo” simply means “human being.” “Ata” also has a derogatory connotation for Manobo leaders who were interviewed (note a similar observation from Bajo 2004, 26). When asked what they called themselves, they referred to the river closest to their settlements: thus, those who live near the Talomo are the “Matigtalomo,” those near the Salug are “Matigsalug,” those near Simong are “Matigsimong,” and so on. The crucial role of rivers in geographical orientation as well as self-ascription must be foregrounded to provide further clarity about what social science scholars mean when they refer to the Manobo living in the highlands of Pantaron.

Despite these distinct self-labels, the Matigtalomo and Matigsimong (on the Davao del Norte province side of the Pantaron mountain range), and the Matigsalug and Matigtigwa/Tigwanon (on the Bukidnon province side), consider each other as kin, and share a common language and material culture, so much so that it can warrant the ascription of a collective name for them. In keeping with their convention of referring to a major prominent feature of their homeland, the term “Pantaron” Manobo after the mountain range that is their ancestral domain is apt.

In the villages covered by this study, many remain un-Christianized and un-Islamized, and still practice subsistence agriculture (rotational or swidden farming; see discussion of “Ata”/“Talaingod” practices in Gloria and Magpayo 1997, 15–90), with land ownership based on usufruct. But today, planting cash crops like abaca and corn and tending small stores are becoming common, as some individuals are drawn into the practicality of procuring some basic needs from the lowlands. This is especially true for villages accessible to motorcycles.

As individuals and as communities, they retain a degree of traditional geographic mobility. Matigtalomo Manobo regularly cross the borders of Talaingod in Davao del Norte and San Fernando in Bukidnon to look for work (often as day workers for clearing fields for planting) and to visit kin. Villages may also move from one location to another, sometimes after the death of an important person in the village (such as a local leader called the datu), and at other times for economic purposes, such as taking advantage of subsistence agricultural lands that may still be more productive. Cultural expressions such as epic chanting, the singing of oranda (short, spontaneous sung verses for welcoming guests and for amusement) and, needless to say, tattooing, are also still practiced.

III Documenting Manobo Tattooing: Historical and Contemporary Accounts

This section presents an overview of the available historical and contemporary documentation of traditional tattooing in Mindanao. The geographical locations mentioned here encompass a wider area than just the Pantaron Mountain range. As far as the authors are aware, there is no such synthesis as yet of these works. It is done here to give other scholars a general view of what had been observed and recorded about traditional tattooing in Mindanao, how it was practiced and what its purposes were, as well as to provide the primary references that may be consulted about this topic.

The earliest mention of tattooing in Mindanao that the authors have encountered was in a letter written by the Jesuit missionary Saturnino Urios to his Mission Superior dated April 12, 1879. In it, Urios related how, while he was in Butuan in northeastern Mindanao, “a flotilla of 27 boats filled with men and women, known in these Mindanao regions as ‘Manobos’” arrived. He described the passengers thus: “They wore their pretty costumes, their hair long, their bodies tattooed like some of the European convicts,” and added that they belonged “to the ranches of lower Agusan” (Arcilla 2003, 46).

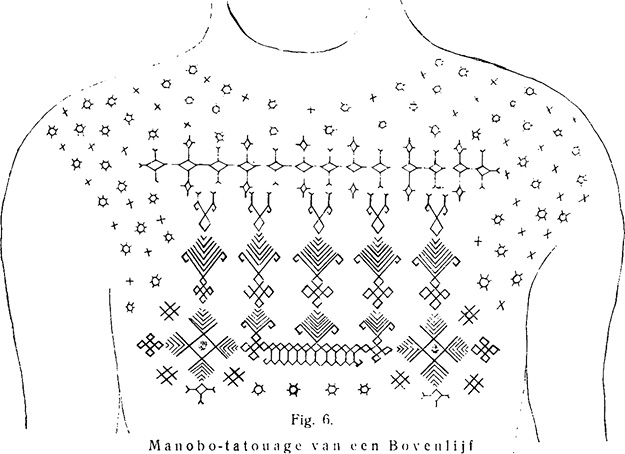

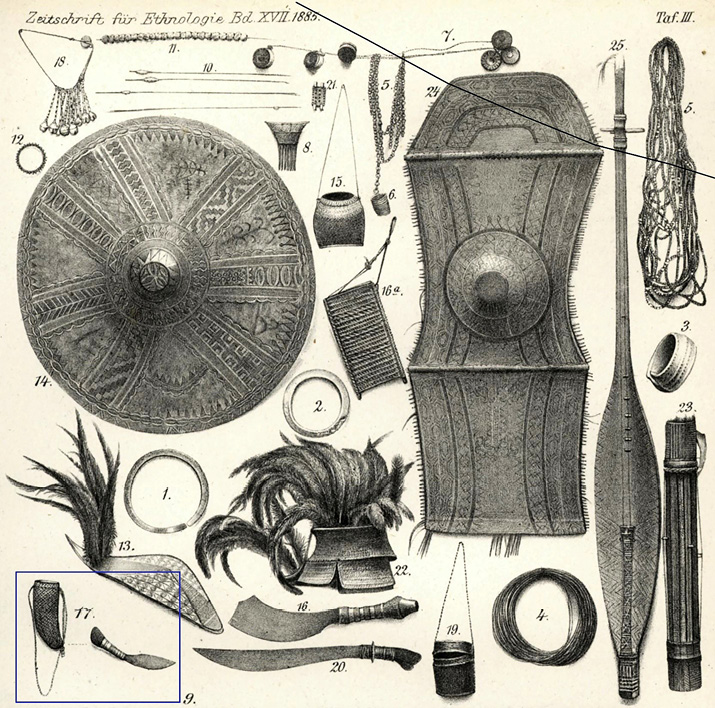

A few years later, from 1881 to 1882, the German explorer Alexander Schadenberg (1885) traveled round Southern Mindanao. He observed how “Bagobo”3) youth (both boys and girls) of the Mt. Apo area were, at the age of approximately 12, tattooed on the arms, hands, chest, and legs. Schadenberg claimed to have seen more than one tattooing session, which he emphasized was carried out not by the Bagobo themselves, but by an “Ata,” a distinct group from the Bagobo. The tattooing involved cutting the skin with a small knife called sagni and then rubbing in soot from burnt bamboo. His publication included an illustration of the tattooed upper arm of a Bagobo, as well as an illustration of the sagni knife used for tattooing. Later in the same decade, the Jesuit missionary Fr. Pablo Pastells briefly mentioned in a letter to his superior that the Manobo in the province of Agusan tattooed themselves by “means of a needle and powdered charcoal” (1906 [1887], 277).

At the turn of the twentieth century, Cole (1913) wrote that the groups of people he called “Tagakaolo” and “Ata” decorated their bodies with tattoos, but that he failed to see any among the “Bagobo.” Benedict (1916), on the other hand, noted that there were “a few cases” of tattooing among the Bagobo, which she wrote was done by an “Ubu (Ata) man, from a place in the far north . . .” (265, parenthesis in the text). Benedict herself was unable to travel to areas inhabited by the group she called Ubu/Ata, and was thus unable to see if and how the Ubu/Ata practiced this amongst themselves. However, her observation of a travelling tattoo practitioner is similar to that noted by Schadenburg three decades before.

The accounts mentioned so far are brief, but the following works of Garvan (1931) and van Odijk (1925) are comparatively more substantial. Both these accounts derive from observations among the Manobo of Agusan, a lowland province to the east of the Pantaron Mountain Range, and so share many details in common. This is generally the same area from which came the “Manobo” that Urios saw in 1879, and that Pastells wrote about in 1887.

According to Garvan and van Odijk, both men and women were tattooed upon the start of puberty. Tattoos were placed on the arms, chest, and torso, but only women were tattooed on the calves. Tattoos were placed by puncturing the skin, and then rubbing the punctured area with soot accumulated from burning tree resin (van Odijk said this resin comes from a tree commonly called dongon-dongon, while Garvan identified this resin as coming from Canarium villosum, with the common name saí-yung).

Van Odijk reported that the tattoo instrument consisted of three needles tied in a bundle. While Garvan did not mention what kind of instrument was used, he wrote about the specialists who were tasked with carrying out this operation. Garvan (1931, 56) stated that these specialists were “nearly always a woman” or persons he described as “hermaphrodites,” individuals who adapted feminine behaviors but did not engage in sexual intercourse.

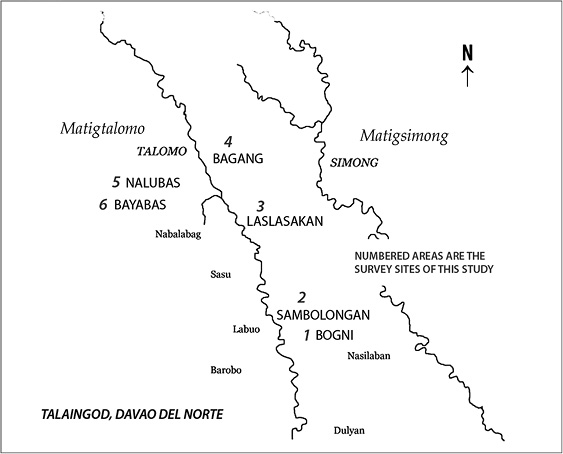

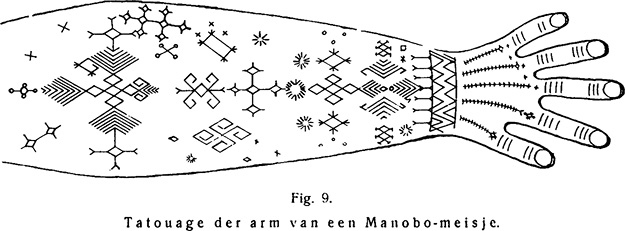

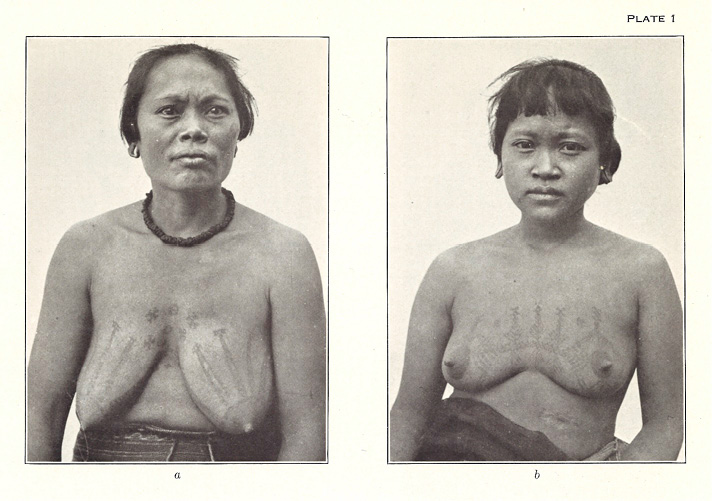

Both Garvan and van Odijk drew comparisons between tattooing and embroidery. Garvan noted that the “hermaphrodites” who were also tattoo practitioners were also skilled in embroidery, and that tattooed designs were similar to those stitched onto jackets. Van Odijk made the same observation, and added that the application of both (tattoos on the skin and stitching on cloth) were done freehand, with no pre-applied pattern to be followed (see Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b). It is following these observations that both authors surmised that the reason tattooing was done was to beautify the body. Van Odijk (1925, 990) called it a “lust for adornment” [lust voor opschik, in the original Dutch] and Garvan (1931, 56) simply said that “tattooing is merely for the purpose of ornamentation.” In relation to this, van Odijk definitely stated that “[t]o be tattooed or not does not indicate recognition of rank or status, of being free or being a slave” [Het niet of wel zich laten tatoueeren duidt niet op erkenning van rang of stand, van vrij-zijn of slaaf, in the original Dutch] (1925, 990), though Garvan wrote that he was told that under Spanish colonial rule, tattoos were also used to identify captives who were sold as slaves.

Fig. 4a Agusan Manobo Chest Tattoo, from Antonius van Odijk (1925)

Fig. 4b Agusan Manobo Arm Tattoo, from Antonius van Odijk (1925)

In the decades after the publication of Garvan’s and van Odijk’s works, no other studies were made of Mindanao tattooing until Manuel’s work among the Manuvu in the Marilog District in Davao City in the 1950s to 1960s (originally published in 1973, and re-published in 2000). Manuel discussed Manuvu tattooing as a rite of passage for adolescents and as a mechanism for fostering social cohesion. Tattooing was carried out on both males and females, and was associated with other bodily modifications such as teeth filing (for both sexes) and circumcision (for boys). Manuel added that both tattooing and teeth cutting were done by specialists who were given “gifts” (Manuel 2000 [1973], 95) (he did not specify what kinds of gifts) in exchange for their services, and that Manuvu parents made sure that their children underwent these processes.

For Manuel, Manuvu tattooing signified group identity, conformity, and inculcating “an integrative we-feeling” (ibid., 305) that subsumed individuals within the larger group. However, Manuel was unable to provide ethnographic cases to demonstrate, nor did he elaborate further on, how tattooing performed these social functions.

Other studies published since only cursorily mention tattooing. A publication by the non-government-institution Tri-People Consortium for Peace, Progress, and Development of Mindanao (TRICOM 1998) reiterated previous general observations of Manobo tattooing on the wrists, legs, waists, and breasts for ornamental purposes or for the identification of captives. Bajo’s (2004) study of Kapalong Manobo briefly mentioned the difference in designs between tattooing for women and men, and that these were meant to be decorative and symbolic of indigenous pride. A comment regarding pangotoeb by Western Bukidnon Manobo Francisco Polenda (2002) is brief enough to be quoted in full:

Another kind of arm ornamentation [zayandayan] is tattooing [pengeteb]. Anyone, men, women, or children may be tattooed [ebpengetevan]. It is done [Emun pengeteb] by making small incisions [penuris: cf. Bahasa Indonesia, menulis, ‘to write’]4) in the skin with a sharp knife [ebpenurisen kes lundis te megarang he kurta] and any design may be made [ibpengeteb is ed-iringen], a name [ngazan], a bird [tagbis], or a human [etew] figure. (Polenda 2002, 158, emphasis and insertion of terms in brackets added; see pp. 391–392 for the original Western Manobo categories used)

Traditional Mindanao tattooing has also been the subject of two television documentaries: “Ang Tipo Kong Babae” (My Type of Woman) by the program I-Witness, which aired on March 7, 2005 (Tima 2005), and the photo-documentary “Burdado” (Embroidered) by the program Reel-Time, which first aired on August 19, 2012 (Arumpac 2012). The former tackled tattooing in the context of notions of beauty among different Philippine indigenous groups, while the latter—which focused on the Manobo of Arakan Valley—attempted to situate tattooing within Arakan Manobo spirituality.

From this review, it is apparent that there is still much that can be done for a properly contextualized and in-depth cultural analysis of Manobo tattooing. Many of these works are limited only to noting that such a practice exists among some Manobo groups. Nevertheless, there are some observations in these accounts that may still help raise relevant questions about Manobo tattooing as it is practiced today and the changes that it has undergone. First, the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century accounts are consistent in pointing out that tattooing was closely associated with specific groups of people: the “Ata” of the Davao highlands (Schadenberg 1885; Cole 1913; Benedict 1916) and the “Manobo” of Agusan (Urios in Arcilla 2003; Pastells 1906 [1887]; van Odijk 1925; Garvan 1931). While the “Bagobo” are also tattooed, it is clear from Schadenberg’s (1885) and Benedict’s (1916) account that they are only able to do so via an “Ata” practitioner. These observations suggest that the native inhabitants of Mindanao recognized distinct groupings among themselves based upon cultural practices like the ability to tattoo. Moreover, these accounts also reflect that tattooing was a channel for mobility of “Ata” practitioners, as well as the interaction between distinct local groups—possibly a sustained practice until the American colonial era.

Though the “Ata” and the Manobo of Agusan are located in contiguous areas in the eastern half of Mindanao, these early accounts also point to different tattooing techniques. According to Garvan (1931, 15), in the Agusan area tattoos are applied with the “puncturing of the skin”; van Odijk (1925, 992) similarly says that with the tool composed of bundled needles, “the skin is punctured according to the figures to be drawn” [Met deze stift beprikt men de huid volgens de te teekenen figuren, in the original Dutch]. In contrast, the only account of tattooing among the Ata (that of Schadenberg’s) tells that they used a short knife that “cuts” or “incises” [ziemlich tiefe Einschnitte, i.e., “pretty deep cuts or incisions” (Schadenberg 1885, 10)] instead of punctures.

The first two techniques resemble that of the indigenous groups in the Cordilleras of Northern Luzon wherein pointed instruments (such as needles) are used, which are either tapped or poked on to the skin. Hand-tapping is also the documented practice among neighboring Austronesian-speaking groups such as the Atayal in Formosa (now Taiwan), the Kayan in Borneo, and in many islands in the Pacific (Krutak 2007; Gell 1993; Thomas 1995). The third technique (after “hand-tapping” and “hand-poking”) is the “cutting” or “incising” technique of the Manobo of Pantaron that is discussed in this article.

Another common observation is that tattooing was associated with puberty, though only Schadenberg and Manuel explicitly stated that tattooing was a rite of passage. Ornamentation was also a commonly cited reason for tattooing. Later sources such as Manuel (2000 [1973]), Bajo (2004), and TRICOM (1998) also include “indigenous pride” and “indigenous identity” as reasons for tattooing. A contribution of the two television documentaries cited above is that the voices and views of the people themselves who practice tattooing have been heard and placed on the record.

IV Manobo Tattoo Practices: Social Relations, Techniques, Body Placements, Designs, Reasons

The Manobo term for tattoo is pangotoeb, and this applies across Manobo groups such as the Agusan Manobo, Arakan Manobo, the Kulaman Manobo, the Matiglangilan, Matigtalomo, and the Matigsimong, the Matigsalug of Marilog and Kitaotao, the Tigwanon, and the Western Bukidnon. The term was first recorded by Garvan (1931), which he spelled, erroneously, as pang-o-túb; based upon the actual syllabication of the Manobo interviewed for this study, it should have been pa-ngo-túb. The following section will discuss five important aspects of Manobo tattooing: (a) social relations of tattoo practitioners and recipients; (b) comparative tools and techniques; (c) body placements and relation to the idea of self; (d) basic elements and designs; and (e) given reasons for having tattoos.

IV-1 Social and Symbolic Relations: Tattoo Practitioner and Tattoo Recipients

The tattoo practitioner, called a mangotoeb, can be either a male and a female. However, notably, all the tattoo practitioners the authors have been able to interview are female. Additionally, all the other practitioners to whom the authors have been referred but have been unable to interview are also female, except for one. Lastly, most of the deceased tattoo practitioners whose names are still remembered are also female. The explanation offered by the Pantaron Manobo was that women tattoo practitioners could tattoo both men and women, while men tattoo practitioners could only tattoo fellow males, because a man touching the body of a woman who was not kin is deemed inappropriate.

This gender pattern is different from the Cordillera peoples in Northern Luzon where male tattoo practitioners were more common (Salvador-Amores 2013, 68). But women being dominantly or exclusively given the role of tattoo practitioner and holder of knowledge related to tattoo meanings is recorded among the Kayans in the early twentieth century (Hose and McDougall 1912a, 252; Hose and Shelford 1906, 68), in southeastern Papua New Guinea (Barton 1918, 24), the Ainu of northern Japan (van Gulik 1982, 192), and the Atayal (Ho 1960, 46).

The skills of the mangotoeb are transmitted informally. Future tattoo practitioners began as children who observed older mangotoeb in practice. These mangotoeb are also often an elder relative such as their mother or aunt. Malin,5) a mangotoeb, recalled how she would spend the whole day with her aunt, who would allow her to observe: “Very early in the morning I would start, until the sun reaches there [points to the west].” Soon after, and without any prodding, these young girls would move on to practice cutting the underside of a cassava peel, which simulates human skin, while others would try tattooing their age-mates, such as close friends, sisters, or cousins.

There is the added element to Malin’s story of having dreamt that she should be a tattoo practitioner after she fell asleep while observing her aunt at work for the first time. She did not expressly read this, however, as a special “message” (as dreams may be interpreted to be)—as she said, it was “just a dream.”

There is no period of formal apprenticeship, but budding practitioners who show a talent for it are encouraged by their older relatives to continue. This informal form of guidance is made possible by the fact that young, would-be mangotoeb practice in open or public spaces (such as in front of their houses) where their work may be seen by others. There is no formal rite of recognition that one has already attained the status of mangotoeb. A mangotoeb begins to be recognized as such when word of her/his skill begins to spread and other fellow Manobo begin to seek out her/his services.

A skillful mangotoeb can be very busy. Malin recalls her aunt working as a mangotoeb: “So many people would come . . . sometimes as much as 10 [in a day]. And sometimes, she would do nothing else for two days straight but to tattoo.” Lunid, whose deceased mother was a famous mangotoeb, claimed that her mother would tattoo from 10 to 15 individuals a day.

What is common among the interviewed tattoo practitioners is the element of enjoyment. As youngsters, they already had an initial attraction to the tattoo practice, which is why they would observe their local mangotoeb at work. They persisted in this role because they “liked” it; in the words of Erinea, a Matigsalug practitioner, tattooing was “kaupiyahan,” or “a joy.”

Both men and women are tattooed. Many elder Pantaron Manobo cannot reckon their exact calendar age, and so their age at their first tattoos cannot be exactly determined. However, they all agree that for the women, their first tattoos were placed before menarche. Both elderly men and women recall that they were first tattooed before marriage. Another way to convey their estimation of their age when they were first tattooed is to point to one of the pre-pubescent children who would always be milling about during interviews and say that “I was that age” when he or she first got tattooed (the ages of these children fall between 8 to 10 years of age).

At present, children are still allowed and even encouraged by their parents to get tattoos. Jo and Min (who were both 15 years of age at the time of the interview in 2015) were 13 and 11 years old respectively when they were first tattooed along with eight other friends. Their parents had told them that a gigantic creature called the Ologasi would eat people who did not have tattoos. Jo added that the tattoo “is pleasing to see,” and that seeing the tattoos of others makes one also want to be tattooed. Their friend Niki, who was 14 years of age at the time of the interview and who was tattooed with her elder sister a few years before, said that they “were thankful” after getting tattooed because they would no longer be taken by the Ologasi. When asked if they were afraid at the time they were tattooed, all three teenagers answered that they were not.

When asked about what preparations they did beforehand, they said that they readied baliog (beads), tikos (leglets made of fiber), and some food that they must give to the mangotoeb. However, being a mangotoeb is not seen by the Pantaron Manobo to be a lucrative occupation or economically rewarding role. Sometimes, as Malin told us with a touch of humor, it was she who had to feed the tattoo recipient: “I would be the one to spend for the person to be tattooed . . . the stomach is soft if it is empty, so it needs to have something inside it so that it will be full and taut [so that the tattoo will be applied better].”

Nevertheless, it is required that the tattoo recipient give even just a small item to the mangotoeb in return. This is similar to Manuel’s observation that a “gift” (2000 [1973], 95) must be given to the specialist who carries out the tattooing. When asked what sort of items can be given, the immediate answers given by mangotoeb and other Manobo adults are the aforementioned beads, leglets, and food. The value of this item is not what is at stake here but rather, the giving of this item serves to “remove the blood from the practitioner’s eyes,” referring to the blood that is shed by the recipient that the tattoo practitioner sees during tattooing. If this blood is not “removed,” it is believed that this will result in the failure of the practitioner’s eyesight in the future.

A similar view was also recorded among the Kayan in the early twentieth century. A small gift generically called “lasat mata” (which may be beads or any small item) must be given to the female tattoo practitioner, and “if it were omitted the artist would go blind” (Hose and McDougall 1912a, 254). In Kayan language, lasat mata literally comes from the categories “eyes” (mata) and “to wipe clean” (lasat)6) (Southwell 1980, 114, 139). This denotes that the name of the gift for the Kayan practitioner follows a similar logic as that of the Pantaron Manobo practice of “removing the blood from the eyes” of the tattoo practitioner, also through gift-giving (although the Pantaron Manobo do not give a special name to the gift given to the mangotoeb).

During the tattoo process itself, the only prohibition, called liliyan or pamaleye, has to do with the recipient grabbing hold of someone as the tattoo is being applied. According to Malin, “If you get a tattoo, you cannot grab on to me even if it is very painful, because I can be victimized during a pangayaw [raid]. . . . If you grab [the mangotoeb], her life is placed in danger. If there is a raid, she will be the one taken, or killed.” For the Matigtalomo (the group to which Malin belongs), grabbing on to anyone while being tattooed will effectively doom that person in a future pangayaw. But for Erinea, a Matigsalug mangotoeb, this restriction applies only to the tattoo practitioner, and that the tattoo recipient may touch other people present as the tattoo is being applied. However, because the researchers have not yet observed first-hand the actual application of the tattoo, the question of whether this taboo is still actively observed is still open for direct verification.

Apart from the requirement of giving an item to the practitioner and the prohibition against grabbing someone whilst being tattooed, the Manobo today do not recount any other practices related to the supernatural in the process of tattooing. There are no prayers said before, during, or after the tattooing, and the recipient can immediately resume normal activities right after being tattooed.

As for post-tattoo care, the mangotoeb recommend that the tattooed portion of the body be covered with clothing for the next three days. Additionally, the portion of the body that was tattooed should not be washed with water in order to keep its dark color. An epiphyte called the kagopkop may also be applied at this stage (see below).

IV-2 Manobo Incising Technique as a Third Modal Technique in Southeast Asian Tattooing

In Northern Luzon, the general term for tattoo is batok (Salvador-Amores 2013). Among the Manobo, the term batok is also present as a verb that refers to a staccato cutting motion. This cutting motion approximates the application of the tattoo using a bladed tool. However, the process of being tattooed is simply called pagpapangotoeb, with the pangotoeb as root word and the prefix pagpa—denoting “the process of,” hence, the process of being tattooed.

The specialized bladed tool for tattoo application is called goppos, but without the goppos the ilab, or a short knife that is also used to prepare betel-chew, can also serve. The goppos or the ilab, held by the practitioner like a pen, is wielded with quick batok motions upon the skin to cut short dashes a few millimeters in length and in depth, producing the basic element of pangotoeb design.

This technique is distinguished from the hand-tapping and hand-poking processes that are both present in the northern Philippine Cordilleras (ibid.). The first important difference concerns the tool: both hand-tapping and hand-poking use a sharp point (such as needles or lemon thorns), either singly or bundled together, hafted onto a wooden stick (ibid., 91, 95). In hand-tapping the stick with the hafted needles or thorns is hit with a separate tool (often another stick) repeatedly. This percussive motion drives the pointed tool to strike the skin with the tip of the needles or thorns to prick the skin and allow the ink to seep in. In hand-poking, the pointed tool is pushed directly by hand by the practitioner to pierce the skin; this does not require a second implement.

“Pricking” the skin is also how early Spanish chroniclers described the tattooing process among the Visayans in the Central Philippines whom they first encountered (Alcina 2012, 143; Chirino 1904 [1604], 205; Bobadilla 1905 [1640], 287; Morga 1904 [1609], 72). Chirino (1904 [1604], 206) stated that pricking was done “with sharp, delicate points,” while Loarca (1903 [1582], 115, 117) claimed that “small pieces of iron dipped in ink” were used. According to Scott (1994), Loarca wrote this account in Iloilo in the island of Panay, and Jocano (2008 [1968], 23), in his very brief description of tattooing among the Sulod of Panay, wrote that tattoos called batæk “are pricked into the skin with a needle or any pointed iron instrument.”

Alcina (2012, 143) described “sharp instruments” or “little combs, made of brass,”7) that “pricked the flesh,” and according to Colin (1906 [1663], 63–64) tattooing was done “with instruments like brushes or small twigs, with very fine points of bamboo. The body was pricked and marked with them until blood was drawn.”

While hand-tapping and hand-poking with pointed tools result in points, cutting with a knife produces dashes. As mentioned above, applying the pangotoeb is similar to the process described by Schandenberg (1885). The ilab knife also resembles the sagni (in Plate III Fig. 17 of his manuscript; see Fig. 5a and Fig. 5b) knife Schadenberg said is used by the “Ata” tattoo practitioner. It is also apparent from the woodcut illustration of an example of tattooing in Schadenberg’s manuscript (in page 10; see Fig. 6) that the overall design is composed of small dashes. Aside from hand-tapping and hand-poking with pointed tools that prick or pierce, the Pantaron Manobo pangotoeb thus presents a third technique in indigenous tattooing in the Philippines that utilizes a bladed tool, and entails incising, or cutting, small dashes instead of puncturing the skin.

Fig. 5a Fig. 5a Bagobo Material Culture, from Alexander Schadenberg (1885); The Bagobo Sagni is in the Square

Fig. 5b Pantaron Manobo Ilab

Fig. 6 Bagobo Tattoo on the Upper Arm, from Alexander Schadenberg (1885)

Among Philippine groups that practice skin modifications, this technique of incising may be comparable instead to the scarification of various Negrito groups as reported by Garvan (1963) in the provinces of Tayabas (now Quezon), Bulacan, Rizal, Zambales, Camarines Norte, and Camarines Sur, all in Luzon. Various tools that were used to wound the skin are bladed implements like the bolo and betel-knife, as well as other tools made of bamboo and stone. However, Garvan did not clarify if certain tools were associated with particular groups or areas, or if different tools were used within the same group or area. Garvan’s illustrations of samples of scarification designs (Garvan 1963, 50) show that the resulting marks also consist of lines and dashes that are similar to the Manobo tattooing.

Outside of the Philippines, among the Ainu, van Gulik (1982, 188) wrote that “no use is made of needles” to tattoo. Instead, they use “a small knife with razor edge by means of which the flesh is incised.” In the survey of tattoo technologies Ambrose (2012) provided in his exploration of connections between tattooing and Lapita pottery, cutting with sharp-edged tools (like obsidian flakes) is present in Melanesia (particularly the Admiralty Islands, New Ireland, New Britain, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia), but is not noted elsewhere in Oceania or Island Southeast Asia. Drawing from historical documentation (from the nineteenth century) of the practice in Manus Island in the Admiralty Islands, Ambrose (Ambrose 2012, 13) described tattooing in the area as “made up of a series of short lines or cuts,” or of “repeated parallel cuts of about 5mm.”

The pigment used for the tattoo is the soot from a chunk of salumayag, or almasiga in Tagalog (Agathis philippinensis [Warb.]), a hardened tree resin that quickly ignites if placed near a flame. The burning salumayag is placed below a kaldero (metal pot), and the accumulated soot from the flame of the burning salumayag is carefully scraped off. This same method of collecting soot for ink is done among the Kalinga (Salvador-Amores 2013), the Kayan (Hose and Shelford 1906, 68), and the Ainu (van Gulik 1982). The mangotoeb then moistens his or her fingers with water, dips them in the collected soot, then rubs the soot on to the wounds that have already been made by the goppos. The pigment is simply allowed to stay onto the wounds without being washed off to ensure that it stays.

Another important plant source is the kagopkop, an epiphyte that has not yet been scientifically identified thus far. This is not used during the time of tattoo application, but when the wounds of the tattoo are healing, as indicated by the itching the recipient feels at the tattooed area. At this stage, heated nodules of kagopkop are rubbed onto the tattooed area not only to soothe the itching, but also to keep the black coloration darkly vibrant. Nowadays, with the reduction of forests from which these plant materials are normally gathered, soot from burned rubber tires is also considered to be suitable ink by some tattoo practitioners.

IV-3 Body Placements of the Tattoos

The mangotoeb say that the recipient’s preferences are followed with regard to what design, what part of the body is to be tattooed, and how extensive the tattoo will be. Currently, adult Manobo also claim that it is up to the individual Manobo whether to get tattooed or not. Thus there are individuals with the complete repertoire of tattoos, some with just a few lines, some with what appear to be unfinished tattoos, and some with no tattoos at all. Not being tattooed is not viewed negatively, and no terms exist which distinguish a tattooed person from a non-tattooed person.

Though there is some leeway for the preferences of the individual recipient, these preferences are limited by the recipient’s sex, prescribed locations, and the suite of designs. The Pantaron Manobo traditionally only tattoo specific portions of the body: the forearms from the wrists up to just below the elbow, around the abdomen and back, breasts, and the distal third of the leg ending at the ankles. Though both Garvan (1931) and Schadenberg (1885) had noted the presence of tattoos on the upper arms, the authors have not encountered members of the older generation of Pantaron Manobo with upper arm tattoos. They generally consider these to be “new” (in Bisaya lingua franca, bag-o) or derived from the modern tattooing of non-Manobo. This may suggest a difference in tattoo placement on the body between the Pantaron Manobo of today on the one hand, and the Agusan Manobo and the Bagobo (as observed by Garvan and Schadenberg respectively) on the other.

There are further regulations with tattoo placement in terms of sex. The forearm tattoos can be found on both men and women, as are those on the breast or chest area (see Fig. 7). But the tattoos on the abdomen and lower leg are said to be restricted to females. While they relate the former to their belief that tattoos can help “ease childbirth,” no reason is provided for the restriction of tattooing on the lower legs to females.

Fig. 7 Pantaron Manobo Male Chest Tattoo

IV-4 Basic Elements and Designs

If broken down to its most basic element, the pangotoeb is composed entirely of short dashes. This is a function of the bladed tool (either the goppos or the ilab) used in tattooing and the batok motion of cutting, rather than puncturing, to which it lends itself best—resulting in short, cut dashes instead of points. Even designs that appear curvilinear from afar are rendered as conjoined short segments of straight dashes.

The short dashes made by cutting are, by themselves, not named, but grouped combinations of dashes are. The identification of these named groups presented an interesting methodological challenge, especially in delineating their borders within, for example, the wider abdominal or forearm tattoo. This was compounded by the blurring of tattoos due to time on the body of our more elderly interlocutors. It was the interlocutors themselves who came up with the solution by simulating tattooing with a cassava peel and applying some soot to allow the patterns to be visible. As explained in the section above regarding the process of becoming a mangotoeb, this technique is one way by which a budding tattoo practitioner trained him or herself. The resulting lines on the cassava peel are neat and well-defined, making it easier to distinguish which dashes go together as group.

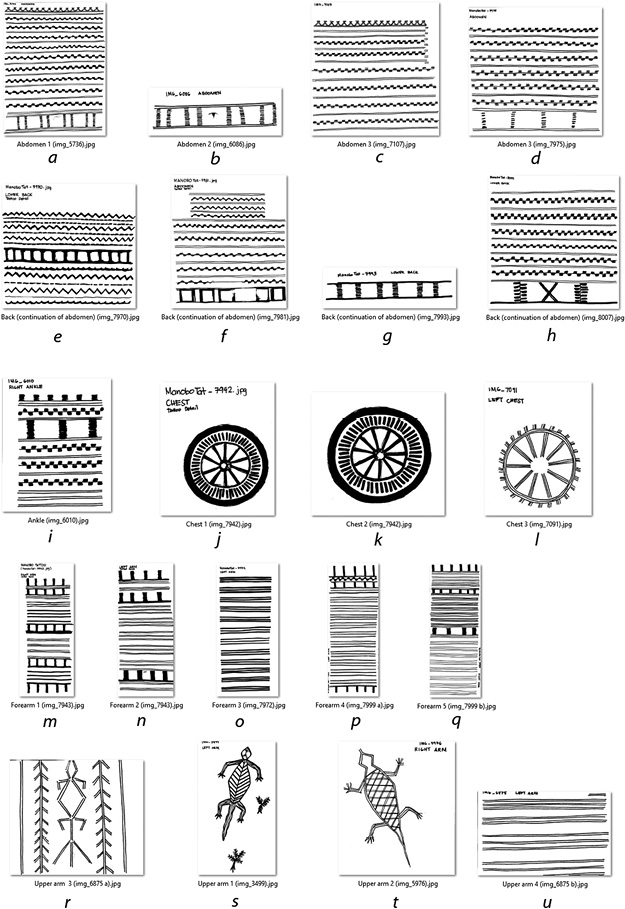

The dominant figural designs of the pangotoeb are simple geometrical shapes like circles, triangles, squares, and lines. Some figurative designs are derived from, or seen as, objects found in nature, such as the paloos (monitor lizard) (Fig. 8 r, s, t), and the salorom (fern) (outer borders of Fig. 8 r). Parallel diagonal lines are called linabud, from a medicinal grass called labud. Other designs are abstract, such as the ngipon-ngipon (teeth-like)—a pair of parallel dashes placed one after another. These segmented dashes sandwich an unbroken straight line called the pisol (the repeated bands in Fig. 8 a, c, d, f, h). The pisol is distinguished from a straight line occurring by itself, which is called a linayon. The linayon, in turn, may either be thin or thick (Fig. 8 n, o, p, q).

Fig. 8 Variation of Pantaron Manobo Tattoo Designs

The ngipon-ngipon and the pisol combination, if it appears on the ankle, is called by a different name: kinorow (Fig. 8 i). This comes from korow, a Manobo time-keeping instrument to remind one of a future event that aids in counting the days prior to that particular event. The korow consists of a strip of rattan knotted according to the number of days; the person holding on to that strip must cut one knot for each day that passes until the event that is waited for arrives.

The panalinsing and tirog are two other distinct named groups of tattoo designs. The panalinsing is commonly a border motif consisting of a central vertical line crossed by several shorter segments along its length which, blurring with age, appears as thick horizontal lines (top borders of Fig. 8 m, n, p, q).

Like the panalinsing, the tirog too can function as a border, but may be integrated within a thicker design band, for example on the forearm (Fig. 8 m, n, q). The tirog is a ladder-like image (Fig. 8 m, n, q). The tattoo practitioners and other Pantaron Manobo adults interviewed were explicit in saying that the tirog functions as the lower border of the abdominal tattoo (which, as a whole, is also referred to as pangotoeb). Indeed, it can be considered the foundation of the abdominal tattoo, for it is the first design band of the abdominal tattoo that is applied (Fig. 8 b, g). Further, practitioners and informed adults are likewise explicit in saying that the placement of this tirog band is based upon the navel. The navel is purposefully centrally placed between the “rungs” and “handles” of the ladder-like tirog (Fig. 8 a, b). The placing of the tirog corresponding with the navel serves as the caudal terminus of the entire abdominal pangotoeb. Once affixed, several succeeding bands of the ngipon-ngipon-pisol group are tattooed on. These are topped with the liliongan design, composed of an inverted “V” and a horizontal dash on top of its apex (topmost layer in Fig. 9). Liliongan is also the term for the ridge-pole of the Manobo house, a significant component of the house structure that will be further discussed below.

Fig. 9 Liliongan or “Ridge-Pole” Design

There is another set of abdominal tattoos that are less commonly placed. This short band, applied below the individual’s navel, is called bagakis (see Fig. 10 and Fig. 11, right), composed of tirog, ngipon-ngipon, and linayon. While the abdominal pangotoeb can occur by itself, the bagakis that the researchers have seen so far only occur with a complete abdominal set, suggesting that the bagakis is placed after the abdominal pangotoeb, possibly at a later stage in the life of the individual.

Fig. 10 Two of our Manobo Interlocutors Who Have Abdomen Tattoos

Fig. 11 Female Abdomen Tattoos; on the Right Picture, Note the Bagakis Design below the Navel

The forearm pangotoeb, present on both men and women, is more a loose combination of designs (some individuals have “mismatching” tattoos on the left and the right arms). The linayon is almost always present (Fig. 8 m, n, o, p, q); less frequently, the tirog, ngipon-ngipon, and figurative designs like the linabud. A forearm tattoo is finished off with the panalinsing border on both the proximal and distal ends of the forearm group (Fig. 8 m and p).

Men and women have breast tattoos, but the designs are different for each sex. The design group (which does not have a properly articulated group name) for men are placed around the nipple; for women it is above it.

The breast tattoo for women consists of linayon, ngipon-ngipon, tirog, and a short band at the top called papinuan. On applying the tattoo, the first mark to be made is a line right above the areola, which, like the tirog corresponding to the navel, demarcates the caudal extent of this tattoo group. This line is called the binunsuran; this term’s root word is bunsud, which primarily means “beginning,” and secondarily as “the foot of the ladder into the house” (SIL 2016, entry on “bunsud”). Binunsuran is also the term for the bottom edge of a shield (banwaloy), which is likewise struck to the ground by a Manobo bagani (warrior) during warrior display. The women’s breast and chest tattoos depicted in Garvan (1931, see Plate 1a and 1b; see Fig. 12) do not resemble the breast tattoos for Pantaron Manobo women. At this point, it can be underlined that these important, and rare, early twentieth-century images from Garvan (1931) (Fig. 12) and van Odijk (1925) (Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b) give some indications of the difference between the tattoo designs of the Manobo of the Agusan plains, and the highland Pantaron Manobo.

Fig. 12 Agusan Manobo Designs, from John Garvan (1931)

The breast tattoo for men is a circular design consisting of several straight lines called dalan extruding radially from the areola, ringed by repetitive panalinsing demarcating the circular pattern (Fig. 8 j, k, l).

IV-5 Why the Manobo Tattoo Themselves

The reason most often spontaneously given for getting a tattoo from both old and young Manobo alike is that it protects the bearer of the tattoo from the creature called the Ologasi. The Ologasi is a giant that is said to eat untattooed persons when the baton (an event similar to the notion of “the end of days”) occurs. The Ologasi appears as a villain in the story of Manobo folk-hero Banlak and his kin as they traveled on a boat to “the other world” where “there was no more death.” According to the tale the authors recorded in 2014, and another version from Bajo (2004, 157–165), the Ologasi blocked Banlak’s company at the portal to “the other world” and demanded that Banlak give the giant his sister in exchange for passage. Banlak agreed, and left his sister behind as the rest of the group made their way to “the world with no death.” That tattoos protect against the Ologasi is also a reason that is present among the Matigsalug Manobo of Marilog.8)

Another common reason for getting a pangotoeb is that the tattoos would serve as a “light” to guide the soul to the afterlife after one dies. Among the Pantaron Manobo, the realm into which the departed enter after death is called the Somolow. This belief appears to be more widely recorded across Mindanao, as this is recorded to be present across these other Manobo groups: the Matigsalug of both Marilog and Kitaotao (Tima 2005), the Kulaman (TRICOM 1998), Kapalong (Bajo 2014), and Arakan Manobo (Arumpac 2012).

The link between tattoos and the afterlife is one that is also widespread among various groups in Southeast and East Asia. Tattoos for the Kalinga served to make one recognizable to and “worthy to live with the deceased ancestors” in the jugkao or afterlife (Salvador-Amores 2013, 133). The same function—of tattoos allowing one entry into the afterlife—was briefly mentioned by an unnamed Spanish chronicler in the sixteenth century for the Ibanags of northeast Luzon (Scott 1994, 264). The Kayan in the early twentieth century believed that after death, tattoos “act as torches in the next world” (Hose and Shelford 1906, 67), without which their souls would be left in total darkness. Also for the Kayan, tattoos on the hands of a successful headhunter was said to allow him to be able to easily cross the single log that served as the bridge into the afterlife. This log was said to be guarded by, and incessantly disturbed by a supernatural being called Maligang, and so being tattooed facilitated a soul’s crossing of it (Hose and McDougall 1912b, 41).

Among the Bugotu of the Solomon Islands in the nineteenth century, the “mark” of an outline of the frigate-bird had to be “cut” on their hands before they were accepted in the hereafter (Codrington 1957 [1891], 180, 257), and a tattooed Ainu woman is “assured of life after death in the realm of her deceased ancestors” (van Gulik 1982, 214). For the Atayal, an ancestral spirit stood guard at the end of a long bridge leading into the spirit world. If the dead person could “pass the test of adulthood”—i.e., tattoos associated with headhunting for men, and exceptional weaving for women—then that person could cross quickly to the other side; if not, souls had to take a longer route to reach their final destination (Ho 1960, 9).

Other cited reasons are more physical than metaphysical. For some Pantaron Manobo, the thick tattoo band that encircles women’s stomachs is believed to ease childbirth. This is echoed by the Arakan Manobo who say that tattoos signify strength for women, and allow them to work in the fields (Arumpac 2012). This association with childbearing and birthing is the only physically therapeutic purpose ascribed to Manobo tattoos, unlike among the Kayan (Hose and Shelford 1906; Hose and McDougall 1912a, 248) and Dayaks (Lumholtz 1920, 347) in Borneo, where tattoos helped cure other illnesses.

Finally, in interviews with some Pantaron Manobo, they also say that the tattoo functions as a marker of their identity, that is, “to be recognized as Manobo” (in Bisaya lingua franca: para mailhan na Manobo). At present, the Pantaron Manobo do not associate tattooing with ascribed or achieved status. Neither do they explicitly consider tattooing as a rite of passage; the recollection of elders that they were tattooed before menstruation and marriage may be suggestive in this regard, but they also do not say that tattooing is today a requirement to become marriageable or to become an established member of Pantaron Manobo society.

V Declustering the Study of Tattooing from Male, Warrior Identity

The preceding discussion of the reasons for tattooing given by the Pantaron Manobo may raise the question of the common association of tattooing with “male” gender roles and “warrior” attributes and activity. This association is reflected in both popularized presentations (e.g. Wilcken 2010; Krutak 2012 [2005]) and academic literature. For example, historian William Henry Scott (1994, 20) plainly states that tattoos among sixteenth-century Visayans “were symbols of male valor: they were applied only after a man had performed in battle with fitting courage and, like modern military decorations, they accumulated with additional feats.” In his typology of groups that remained “unhispanized” until the end of the Spanish colonial period, Scott (1982, 132) underlined that in “warrior societies” (such as the Agusan Manobo, Mandaya, Bagobo, Tagakaolo, Blaan, Isneg, Tingguian, and Kalinga), a “distinct warrior class . . . are recognizable by distinctive costume or tattoos.”

Following this line, Junker (2000, 348) categorizes tattoos as “warrior insignia” that signified success in warfare and the prestige that comes with it. More recently, in arguing that the body (lawas) is instrumentalized by the community’s inner self (kaloobang bayan), Villan (2013, 69) asserts that it is the “duty of the tattooed (Visayan) warriors” (or nabatukang hangaway)9) to “maintain the life, breathing (ginhawa), and pride (dangal)” of their community (bayan) through “raiding (pangangayaw) and waging of battles [against the enemies] (pangungubat).”

In the case of sixteenth-century Visayas, a close rereading of the primary sources will show that tattooing as such was not the exclusive domain of “warriors.” Women, who presumably did not fulfill “warrior” roles, were nevertheless tattooed as well, albeit to a lesser degree (Chirino 1904 [1604]; Alcina 2012; also see The Boxer Codex [Souza and Turley 2016]).10) Amongst the men, Alcina’s (2012) reliable account is informative in this regard:

. . . one thing is certain: all the Bisayan men usually tattooed themselves, except those who were called asug. . . . Not all, however, practiced it in the same way nor did they execute it all at one time.

They began tattooing themselves at about the age of twenty years and up; although some, overcome by fear, deferred it until they were filled with shame when a little older they agreed to allow themselves to be tattooed.

. . . Among them it was a sign of cowardice not to tattoo oneself, for they said that if such an individual lacked the courage to suffer the pricking of friendly needles, how could he ever bear the pain of the spears of the enemy?

For this reason, the bravest among them would add more tattoos, aside from the customary ones. (Alcina 2012, 141, 143, emphasis added)

Alcina then proceeded to describe a set of designs that he described to be “the ordinary type of tattooing used by all of them” (ibid., 143). His observations imply that tattooing was an ordinary practice that can be present among men and women of whatever status and social-heroic expectations. Further, the distinction of those who were recognized as “bravest” lay not in the presence of tattoos per se, but the amount or degree of their application. As Esteban Rodriguez (Anonymous 1903 [1559–68], 126) of the Legazpi expedition observed in 1565, “these Indians wear gold earrings, and the chief wears two clasps about the feet. . . . All the body, legs, and arms are painted; and he who is bravest is painted most” (ellipse in original published text).

The close association between tattooing and warrior identity was reinforced in American colonial scholarship on the “headhunters” of the northern Cordilleras, and this frame has persisted even in recent studies, as Salvador-Amores (2002, 110) noted. In response to this, she endeavored to uncover other meanings, symbols, and functional roles of Kalinga tattooing apart from, or beyond, this familiar frame (Salvador-Amores 2002). Nevertheless this remains to be the point of departure of her study on ritual, identity, and tattoo decline in Ilubo, Kalinga (ibid.), and she continued to grapple with this question in her more extensive treatment of Butbut tattooing (Salvador-Amores 2013), where she wrote:

A number of sources suggest that Butbut tattooing is best understood within the context of headhunting and of the maingor (warriors). I have long argued that for the Kalinga, tattooing is not only associated with headhunting, but that it has a deeper cultural meaning. Tattooed elders told me that in the past, whiing (chest tattoos) men denoted bravery exhibited in defending the village against enemy attacks. The tattoos also determined which hierarchical social roles the men would occupy (ibid., 115–116, emphasis added).

The present article believes that this common and popular axiom of closely associating “tattooing” with “warriorship” (and “headhunting” or “social hierarchy”)—almost elevated as the paradigm when approaching Philippine indigenous tattooing—needs to be fully reassessed. The possible appropriation of tattooing by a “warrior group” within a broader (tattooed) community, like the colonial-period Kalinga, (maingor, Salvador-Amores 2013) must explicitly be addressed as a separate inquiry in itself. Scott (1982, 144), approaching from a different direction, had already placed a finger on the issue when he wrote that the “class of warrior elite” was “not a warrior class among nonwarriors, but a class of superior warriors in a society where all males are expected to be warriors”—probably a fitting description of sixteenth-century Visayan society. Philippine tattooing as an object of study thus needs to be declustered from this spontaneous “warriorship” paradigm. It is not a historical nor ethnographic given that our understanding of indigenous tattooing be confined to “raiding” and “warriorship” (or as indicative of “courage” and “heroism”). As the current study shows, tattooing among the Pantaron Manobo assumes a totally different baseline configuration. The next section details the social domains in which Pantaron Manobo tattooing is located.

VI Towards a Heuristic Schema Underlying Pantaron Manobo Tattooing

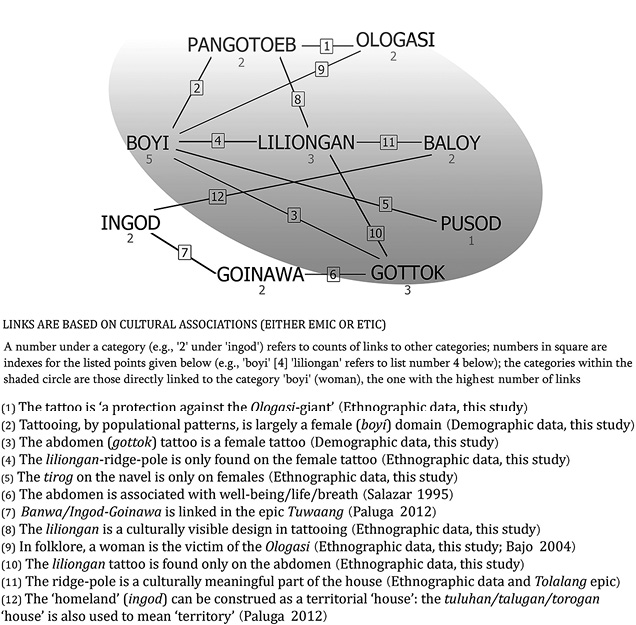

The ethnographic, geographic, and demographic data, even at this preliminary phase, surfaces important elements which, when taken together, form lines of association or concordance. The most important element in Pantaron Manobo tattooing is the central role of the “female” gender, both in the socio-demographic and the symbolic realms. Two other objects are associated with this female figure in Pantaron Manobo tattooing practice: (a) the unique importance of the navel/abdomen as a tattooing region of the (female) body; and (b) the significance of the “ridge-pole” (and other parts of the house) as a named tattoo motif. These appear to be more resonant with many other aspects of Pantaron Manobo culture to warrant giving this schema (this female—navel/abdomen—ridge-pole/house links) a heuristic value that will be expanded below.

That tattooing can be said to be predominantly “a female domain” is consistently shown in the ethnographic and demographic data (see Fig. 13). Overall, more females tend to be tattooed than males: 82% of females aged 10 years and above11) are tattooed, as opposed to only 46% of males above 10 years of age. This pattern is also true across each village surveyed. Females also appear to receive tattoos earlier: all three individuals who were younger than 10 years of age and who had tattoos were girls. With regard to the sex of the tattoo practitioner, a significant majority (89%) of the tattooed individuals reported that they were tattooed by a female practitioner. At present, although the Pantaron Manobo do not say that it is forbidden for males to become a tattoo practitioner, the tattoo practitioners identified in the course of this research were all females except for one. It is relevant to note here again that women tattoo practitioners enjoy more flexibility in their practice in terms of touching the bodies of both female and male recipients.

Fig. 13 Highlights of the Tattooing Survey Results

There are body locations of tattoos that they say are exclusively female, namely, the abdomen and the lower leg. As given above, there are only four traditional body areas that are preferentially tattooed: the abdomen, the forearm, the breast, and the lower leg. Across the six villages, the abdomen is the body part most frequently tattooed, consisting of more than half of the recorded tattoos (54%). While the leg tattoos are too rare to impact the demographic figures, the assertion that this is a “female” tattoo is made by the Pantaron Manobo, and Garvan (1931) and van Odijk (1925) make the same observation among the Agusan Manobo.

The “ridge-pole” of the “house,” as mentioned earlier, is a prominent figure in abdomen tattoo images. As an architectural element, this object is also rife with symbolic meaning. In the epic narratives of the Pantaron Manobo and in their ordinary conversation, the forging of relations between families through marriage is expressed as “linking the liliongan of two houses.” For Austronesian homes, the ridge-pole is what Fox (2006, 13–14) calls a common “ritual attractor” that may be specially decorated and where ancestor spirits and supernatural forces dwelt or converged. And with the overall visual prominence of the roof in traditional houses in Southeast Asia, the roof is often taken to be a synecdoche for the house structure as a whole and the social relations contained within it (Waterson 2009).

From another line of associational link, the navel, which marks the beginning of the abdominal tattoo, is an important symbolic link to pregnancy, childbearing, and, again, the house. In some groups in the Philippines and Southeast Asia, the keeping or burying of the umbilical cord and placenta of children born in a particular house within its environs is a practice that is said to ensure their safety, and to forge a connection between them (these children may leave their home and family of orientation as they grow older) and hearth and home (Cannell 1999; Ng 2006). The abdominal tattoo’s image, the whole complex layers of figures taken as one, is in fact also read by one of our interlocutors as denoting a “house” in general.

The protective function of the tattoo also has a gendered dimension, as the victim of the Ologasi creature is the female sibling of Banlak. That tattoos protect a person physically (for example, in childbirth) and spiritually (against malevolent creatures) could be related to the abdomen (and its internal organs) as the seat of well-being across various Filipino ethnolinguistic groups (Salazar 1995 [1977]; Paz 2008), as captured by the pan-Philippine category ginhawa. Ginhawa and its cognates, such as goinawa in Manobo, are related to physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being, as manifested in being able to “breathe well” and take in nourishment (Paluga 2012; Salazar 1995 [1977]). Lastly, the belief that tattooing eases childbirth relates it further to females.

In sum, there is a heuristic case to be potentially pursued in future Manobo tattooing studies that should trace these entities, figures, and metaphors linked to what the authors want to point as a “female—abdomen/navel—house/ridge-pole” schema. This schema can be seen as linking “tattooing” (pangotoeb) to at least eight other local Manobo categories: the “ridge-pole” (liliongan) of the “house” (baloy); the “abdomen” (gottok); the “navel” (pusod); the “female” (boyi) gender role; the “giant of the portal to the other-world” (Ologasi); the concept of “breathing and well-being” (goinawa); and the idea of “‘homeland” (ingod) (see Fig. 14).

Fig. 14 Pangotoeb and Other Linked Categories

Because the idea of an “ancestral domain” is, needless to say, a sustained view among Philippine indigenous peoples, the figure of the Pantaron Manobo “homeland” (ingod) cannot be overemphasized, especially in the context of tattooing. Two villages along the Talomo appear to be geographic “way-points” that play an important role in tattooing. The villages of Laslasakan and Bagang are most often reported to be the village of origin of tattoo practitioners: 19% of respondents say that their practitioner had been born in Laslasakan, while 16% say that theirs had come from Bagang. This result suggests two possible interpretations: either many tattoo practitioners were born in these villages, or the most prolific tattoo practitioners (even if they are in actuality few in number), were born in these villages. These two villages are also the most frequently reported location where respondents say they got tattooed (19% in Laslasakan and 15% in Bagang).

That Laslasakan and Bagang are the two most prominent villages for tattooing fits their being culturally meaningful to the Pantaron Manobo who live along the Talomo River. Based upon the authors’ earlier ethnographic work, Bagang appears to be a spiritual center where Manobo baylan or spiritual practitioners (shamans and healers) periodically converge during times of crisis. This meeting, called pahahano, is signaled when baylan from different villages have the same dream. They thus come together to discuss the possible portents of such an event, to chant the epic entitled Tolalang, and to listen to the admonitions of their bujag (elders).

On the other hand, if Bagang is more of a spiritual center, Laslasakan is historically linked to more “secular” but specialized pursuits like metalworking. Laslasakan is also recognized even among the Manobo themselves as the village famous for the oranda, their spontaneously sung verse substantially shorter and more variable than a fixed, full-length epic. The authors infer that tattooing straddled the “sacred” and “profane” spheres of Manobo life, an inference that is also supported by the direct ethnographic data and data from the literature of the spiritual and “practical” correlates of the practice.

To conclude, this article posits as a heuristic guide that entities linked by our proposed schema fall into place as longue durée category-nets with several lines of association in social, symbolic, and demographic levels. Seeing them as a network of notions (or cognitive and linguistic categories) with degrees of cultural valence gives us a glimpse of what it is like to “think about and do tattooing” in the world of the highland Manobo. What this evokes is a limited but meaningful cluster of terms or objects featuring “irresistible analogies” (Bourdieu 1990), operative as a durable schema among the Pantaron Manobo.

Accepted: March 15, 2019

Acknowledgments

Initial seed funding for this study was provided by the University of the Philippines-Mindanao Office of Research in 2013–14. More substantial support in 2015 was provided by the University of the Philippines-System Enhanced Creative Work and Research Grant (Grant Number ECWRG-2015-1-004). AM Ragragio’s Early Career Grant (Grant Number EC-KOR-45049R-18) from the National Geographic Society allowed more intensive fieldwork for this research. Our BA Anthropology students, Petal C. Cagape, Geallaika O. Delideli, Karen Joyanne B. Chua, and Rose Marry Tranquilan, collected the survey data, and conducted interviews, transcriptions, and translations during the 2014 evacuation of the Pantaron Manobo to Davao City. An earlier version of this article was read and commented upon by Ramon Guillermo and Zeus Salazar. The comments from the anonymous reviewers have greatly refined and sharpened the arguments of this article and are very much appreciated.

All photos made as basis for the figures were taken by AM Ragragio and Anthony Montecillo, which were rendered into figures by Sherwin Puntas. Fig. 1 composite photo was taken by M. Paluga. All maps were processed by M. Paluga using georeferenced data from NAMRIA topographic maps and the PRISMA software of PBCP (Philippine Biodiversity Conservation Priorities).

References

Alcina, Ignacio Francisco. 2012. History of the Bisayan People of the Philippine Islands. Part One, Book 1, Volume 1. Translated, edited, and annotated by Cantius Kobak and Lucio Gutierrez. Manila: UST Publishing House.

Ambrose, Wal. 2012. Oceanic Tattooing and the Implied Lapita Ceramic Connection. Journal of Pacific Archaeology 3(1): 1–21.

Anonymous. 1903 [1559–68]. Resume of Contemporaneous Documents. In The Philippine Islands 1493–1898, edited by Emma H. Blair and James A. Robertson, Vol. 2, pp. 77–160. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company.

Arcilla, Jose S., ed. 2003. Jesuit Missionary Letters from Mindanao, Vol. 6. Manila: University of the Philippines-Center for Integrative and Development Studies, and the National Historical Institute.

Arumpac, Alyx Ayn. 2012. Pang-o-tub: The Tattooing Tradition of the Manobo. GMA News Online. http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/271561/newstv/reeltime/pang-o-tub-the-tattooing-tradition-of-the-manobo, accessed May 11, 2015.

Bajo, Rolando O. 2004. The Ata-Manobo: At the Crossroads of Tradition and Modernization. Kapalong City: CARD-Davao.

Banks, Marcus. 2007. Using Visual Data in Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications.

Barton, F. R. 1918. Tattooing in South Eastern New Guinea. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 48 (Jan.–Jun.): 22–79.

Benedict, Laura Watson. 1916. A Study of Bagobo Ceremonial, Magic and Myth. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 25(May): 1–308.

Bobadilla, Diego de. 1905 [1640]. Relation of the Filipinas Islands. In The Philippine Islands 1493–1898, edited by Emma H. Blair and James A. Robertson, Vol. 29, pp. 277–311. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Cannell, Fenella. 1999. Power and Intimacy in the Christian Philippines. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chirino, Pedro. 1904 [1604]. Relacion de las Islas Filipinas. In The Philippine Islands 1493–1898, edited by Emma H. Blair and James A. Robertson, Vol. 12, pp. 169–321. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co.

Codrington, R. H. 1957 [1891]. The Melanesians: Studies in their Anthropology and Folk-lore. New Haven: HRAF Press.

Cole, Fay-Cooper. 1913. The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Colin, Francisco. 1906 [1663]. Native Races and Their Customs. In The Philippine Islands 1493–1898, edited by Emma H. Blair and James A. Robertson, Vol. 40, pp. 37–98. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company.

Fox, James J. 2006. Comparative Perspectives of Austronesian Houses: An Introductory Essay. In Inside Austronesian Houses: Perspectives on Domestic Designs for Living, edited by James J. Fox, pp. 1–30. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

―. 1980. Models and Metaphors: Comparative Research in Eastern Indonesia. In The Flow of Life: Essays on Eastern Indonesia, edited by James J. Fox, pp. 327–333. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Garvan, John M. 1963. The Negritos of the Philippines. Horn-Wein: Verlag Ferdinand Berger.

―. 1931. The Manobos of Mindanao. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Geirnaert-Martin, Danielle C. 1992. The Woven Land of Laboya: Socio-cosmic Ideas and Values in West Sumba, Eastern Indonesia. Leiden: Centre of Non-Western Studies, Leiden University.

Gell, Alfred. 1993. Wrapping in Images: Tattooing in Polynesia. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Gloria, Heidi K.; and Magpayo, F. R. 1997. Kaingin: Ethnoecological Practices of Upland Communities in Mindanao (Ata, Dulangan Manobo, Higaonon). Davao City: Ateneo de Davao University.

Godelier, Maurice. 2018. Claude Levi-Strauss: A Critical Study of His Thought. Translated by Nora Scott. New York: Verso.

Guillermo, Ramon; Paluga, Myfel Joseph; Soriano, Maricor; and Totanes, Vernon R. 2017. 3 Baybayin Studies. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

(van) Gulik, Willem R. 1982. Irezumi: The Pattern of Demography in Japan. Leiden: EJ Brill.

Ho Ting-Jui. 1960. A Study on Tattooing Customs Among the Formosan Aborigines. Bulletin of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology 15–16(Nov.): 1–48.

Hose, Charles; and McDougall, William. 1912a. The Pagan Tribes of Borneo, Vol. 1. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited.

―. 1912b. The Pagan Tribes of Borneo, Vol. 2. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited.

Hose, Charles; and Shelford, R. 1906. Materials for a Study of Tatu in Borneo. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 36(Jan.–Jun.): ix, 60–91.

Jocano, F. Landa. 2008 [1968]. Sulod Society: A Study in the Kinship System and Social Organization of a Mountain People of Central Panay. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Junker, Laura Lee. 2000. Raiding, Trading and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdom. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Krutak, Lars. 2012 [2005]. Return of the Headhunters: The Philippine Tattoo Revival. Lars Krutak Tattoo Anthropologist. https://www.larskrutak.com/return-of-the-headhunters-the-philippine-tattoo-revival/, accessed January 10, 2019.

―. 2007. The Tattooing Arts of Tribal Women. London: Bennet & Bloom.

Lebar, Frank M. 1975. Ethnic Groups of Insular Southeast Asia, Vol. 2: Philippines and Formosa. New Haven: Human Relations Area Files Press.

Loarca, Miguel de. 1903 [1582]. Relacion de las Islas Filipinas [Narrative of the Philippine Islands]. In The Philippine Islands 1493–1898, edited by Emma H. Blair and James A. Robertson, Vol. 5, pp. 34–187. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company.

Lumholtz, Carl. 1920. Through Central Borneo, Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Manuel, E. Arsenio. 2000 [1973]. Manuvu Social Organization. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Morga, Antonio de. 1904 [1609]. Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas [Events in the Philippine Islands]. In The Philippine Islands 1493–1898, edited by Emma H. Blair and James A. Robertson, Vol. 16, pp. 25–209. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company.

Mosko, Mark S. 2009 [1985]. Quadripartite Structures: Categories, Relations and Homologies in Bush Mekeo Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ng, Cecilia. 2006. Raising the House Post and Feeding the Husband-Givers: The Spatial Categories of Social Reproduction Among the Minangkabau. In Inside Austronesian Houses: Perspectives on Domestic Designs for Living, edited by James J. Fox, pp. 121–144. Canberra: Australian National University Press.