Contents>> Vol. 7, No. 3

Getting More Women into Politics under One-Party Dominance: Collaboration, Clientelism, and Coalition Building in the Determination of Women’s Representation in Malaysia

Maznah Mohamad*

*Department of Malay Studies and Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National University of Singapore, Block AS8, #06-03, 10 Kent Ridge Crescent, Singapore 119260

e-mail: mlsmm[at]nus.edu.sg

DOI: 10.20495/seas.7.3_415

Malaysia’s representation of women as parliamentarians remains one of the lowest in comparison to other Southeast Asian and global parliamentary democracies. However, when contextualized against Malaysia’s politics of divides and dissent starting from 1999 onward, there are some newer characteristics of women’s involvement in formal politics. This paper explores the specificities of women’s experience in formal politics under the one-party dominant rule of the National Front before it was defeated in the May 2018 general election. The paper questions various incidents of political transitioning from an old to a newer political regime. Processes such as the collaboration between women’s civil society and formal state political actors, the cultivation of clientelist and patronage relations, and the maintenance of a cohesive multiparty coalition as a strategy for electoral advantage have all had fruitful bearings on the way the formalization of women in politics has developed. However, given the insufficiency of these developments for increasing women’s representation, this paper proposes the more reliable gender quota or reserved seats mechanism as one of the considerations for gender electoral reform.

Keywords: Malaysian women, politics, election, representation, gender quota, electoral reform

Introduction

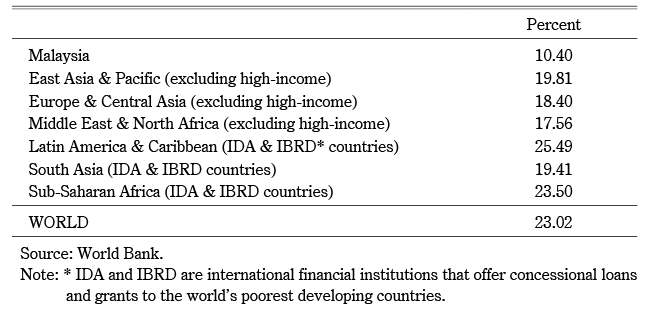

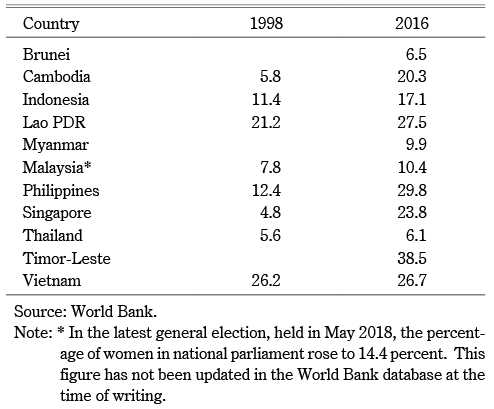

Despite the best efforts of both the government and civil society, Malaysia’s proportion of women parliamentarians remains one of the lowest in the world (Joshi and Kingma 2013, 361). As of March 2017, Malaysia ranked 156th out of 190 in the global list compiled by the Inter-Parliamentary Union (Women in National Parliaments). Female political representatives in its national parliament are fewer than those in other regions and continents (see Table 1). Within ASEAN Malaysia ranks fourth from the bottom, above Brunei, Thailand, and Myanmar (see Table 2). However, of these four, Malaysia has been the longest stable democracy with regular parliamentary elections.1) This record of low female participation in elected and political office should thus be of concern to scholars, social activists, and policy makers alike. The question of maximizing women’s representation is not least a human rights issue, as women make up slightly more than half of all voters in Malaysia. In the general election of 2013 (GE13), female voters comprised 50.23 percent of all voters (Kartini 2014, 107). In the 14th and latest general election (GE14) the proportion had risen, with 7.3 million women making up 50.44 percent of total registered voters (Star Online 2017). As early as 1976 women had already formed half the membership of Malaysia’s largest political party, UMNO (United Malays National Organisation) (Noraini 1984, 249).

Table 1 Proportion (percent) of Seats Held by Women in National Parliaments: Malaysia in Comparison to Other Regions, 2016

Table 2 Proportion (percent) of Seats Held by Women in National Parliaments in ASEAN Countries, 1998 and 2016

Increasing women’s representation in politics recognizes the value of women as an important political group deserving of a say in decision-making processes. It is believed that the formal political sphere will benefit from certain attributes that women can bring, and that not involving women at this level would be nothing less than an “affront to the ideals of democracy and justice” (Lister 1997, quoted in Tan and Ng 2003, 109). Having a critical mass of women in decision-making positions would increase the odds of improving the effectiveness of female politicians and of evoking real change for women (Tan and Ng 2003, 111–113). Another reason why it is important to increase women’s participation in politics is due to the policy commitment that Malaysia has made as a signatory to the United Nations treaty on women’s equality, or CEDAW (Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women). Having endorsed CEDAW, Malaysia is obliged to ensure equality for women in political and public life by implementing policy measures to ensure their equal participation.2) Undoubtedly there has been no overt, explicit, or legal discrimination against the participation of Malaysian women in the public and political sectors. Nevertheless, there have been no vigorous or sustained measures to ensure that women are as visible as men in political office.

This article largely limits the research observation to the period before Malaysia’s 14th and latest general election held in May 2018 (GE14). The study is focused on looking at the dynamics of gender reforms under a one-party dominant state. It documents some of the efforts of the state, civil society, and political parties to navigate their way through Malaysia’s sociopolitical context to increase women’s participation in political office. Since 2008 there has been an atmosphere of a political transitioning, with the incumbent ruling party being challenged through the loss of its two-thirds parliamentary majority and the control of two key states—Penang and Selangor—by opposition parties since the last two consecutive GEs. The ruling coalition, BN (Barisan Nasional, National Front), had never lost an election from the country’s independence in 1957 until the 2018 general election. Three conditions are examined as outcomes of this political transitioning, as they relate to women’s role in politics: (1) the collaboration between women’s civil society interest groups and formal state political actors in building institutions for change, (2) the cultivation of clientelist and patronage politics among women politicians in retaining and expanding the constituent support base, and (3) the maintenance of a cohesive multiparty coalition in strategizing for electoral advantage as it relates to women’s changing roles in politics. The three factors have some bearing on how the formalization of women in politics has developed in Malaysia, or the country’s path toward the “feminisation” of politics (Rai 2017). This article assesses the extent to which these three outcomes have affected the way women participate in formal politics, and whether newer forms of participation arising from these outcomes can lead to an increase in women’s representation in formal politics.

Reviewing Malaysian Women’s History of Political Underrepresentation

For at least three decades previous studies on women’s political role and participation in politics have consistently recorded their underrepresentation in political office and their secondary roles within their political parties (see Manderson 1980; Noraini 1984; Dancz 1987; Jamilah 1992; 1994; Karim 1993; Rashila and Saliha 1998; 2009; Tan and Ng 2003; Tan 2011; Sharifah 2013; Kartini 2014). Exclusionary cultural and social norms, unequal gender division of labor leading to a productive/reproductive divide and gender asymmetry within the labor market, as well as structures of centralized or decentralized governance can make a difference in the way women participate in formal politics (Rashila and Saliha 1998, 99–101; Tan 2011). The other general factors identified as impediments are the “glass ceiling,” “double burden,” and “invisible woman” syndrome (Ng and Lai 2016).

Cultural and ideological factors have been blamed as major contributors, with women themselves not wanting to be in the forefront of political activism and leadership due to prevailing gender norms about the suitability of roles for men and women (Manderson 1980; Rashila and Saliha 1998; Kartini 2014). For example, the precursor to Wanita UMNO, the Kaum Ibu, whilst very active during election time was only partially successful as a special interest group (Manderson 1980, 167–192). The Kaum Ibu, although impressive in its organizational capacity and visibility, remained subordinate to UMNO and its male leaders, as women were expected to “have a role outside the home provided it is supportive of the role of men” (ibid., 202). Furthermore, the division of roles within UMNO allowed for “traditional values and attitudes” to be carried into and “accommodated within quite non-traditional settings, structures, and activities” (ibid., 207). A survey in the 1990s on women politicians and voters indicated that qualities such as “friendly disposition,” “extrovert personality,” “interest in extra-curricular activity,” and “confidence in intersexual mixing” would be needed to provide for a successful political socialization of women (Karim 1993, 112). However, women did not necessarily prefer women candidates over men, although they were gender-neutral when it came to voting for the right candidates (ibid., 126). As a whole, women do not view politics as an important strategy for status elevation. This view is reinforced by conventional views of “dirty politics” and a preference for stable, high-status professions that are less taxing on the self and family (Mulakala 2013). Hence, while professional achievement is an important goal, political achievement is not.

However, structural factors—primarily political party structures—are equally to be blamed for creating barriers to women’s progression in leadership roles within and outside the party. Reasons for a low numerical or descriptive representation of women include the way political parties select candidates, especially in relation to the status of women’s wings as an appendage of the party (Tan 2011, 102). With regard to the latter, a recurrent feature of all Malaysian political parties is their auxiliary branches, or wings (which include those for women, young women, and youths). One study of women in politics focused on their roles within party auxiliaries and found them to be strategically significant and essential though secondary when it came to decision making and leadership of their parties (Dancz 1987). The existence of party auxiliaries inherently limits women’s autonomy in decision making within party structures: one needs to be the head of a party division in order to be selected for candidacy or ministership in the cabinet (Maznah 2002; Derichs 2013). But very few women have ever been the heads of party divisions or branches. Only the head or deputy head of a women’s wing has conventionally been appointed as cabinet minister (Jamilah 1994, 112). It is difficult for women to be nominated or elected to executive positions at the local level of party leadership, such as the party branch or division level (Noraini 1984, 249). As women’s wings occupy a subordinate status within their parties, women’s nomination to stand as elected leaders is prioritized lower than those from the main, central party wing. Subsequently, when women are nominated and then elected, it is not unexpected for them to be beholden to their male patrons within the party. In this atmosphere of quid pro quo deals, women politicians tread carefully between toeing dominant party lines and appeasing women’s rights lobbyists, usually to the detriment of the latter. Such a compromising and wavering posture typically ends up with women politicians contributing very little toward the democratization of gender politics, within as well as outside their party structure (Maznah 2002).

Highlighting the role of party structures, Claudia Derichs lists at least three reasons that impede Malaysian women politicians from having fair competition with their male counterparts. First, there is no encouragement from men for women to rise to the highest ranks within the party. A second reason for the poor record of women being fielded and elected is the first-past-the-post system in which the winner takes all, thereby reducing the chances of women being selected as candidates. The third reason is ethnic politics, which trumps gender as the distributive goal in Malaysian politics (Derichs 2013, 304–305). Derichs particularly emphasizes the inhibiting role of the women’s wing structure of almost all political parties in Malaysia:

Entering politics through the women’s wings is a dead end street, so to speak, unless one becomes the leader of the wing . . . but women are locked within the channel of the women’s wing. Those who seek a high position (minister, deputy minister etc.) would rather enter the party from a different angle and secure support for themselves from various divisions of the party. (ibid., 304)

However, even in the early years women showed their frustration with male leaders not acknowledging their capability as leaders. In 1954 women threatened to boycott the elections if they were not allowed to stand as candidates but were expected to play their roles as voters and vote canvassers (Manderson 1980, 149–150).

Factors such as the rural-urban divide, ethnic relations, and class differences have not been shown to affect women’s participation in politics. In Malaysia, like elsewhere, gender cuts across party affiliations, but with ideological, religious, or ethnic identities prevailing as dominant features (Htun 2004). In Malaysia mono-ethnic parties are legally allowed to exist and in fact predominate, with UMNO and Islamic Party of Malaysia (PAS) being open only to Malay-Islamic members. Members of the Malaysian Chinese Association and Malaysian Indian Congress are likewise from their respective ethnic groups. In all of these cases gender identity is overshadowed by the ethnic interests of the party. Gender equality has thus been sidelined as a concern in these political parties. For example, political activity of women in UMNO was driven more by a need to achieve “communal nationalism” than by a need to realize women’s interests. Women’s active participation in party politics was ultimately recognized as crucial for the party’s survival (Noraini 1984, 222–240, 390). A study of ethnicity-based non-Bumiputera (non-indigenous) political parties showed an equally difficult path for women of all ethnicities to achieve high positions within their parties (Mahfudzah 1999). As for class or clan influence, it has been found that among some Malay women their early entry into formal politics was determined largely by male patronage or through a dynastic male line (Rogers 1986; Shamsul 1986). Among the current prominent female leaders, particularly Wan Azizah Wan Ismail—who heads the opposition political party Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR, People’s Justice Party) and is Malaysia’s deputy prime minister—there is clearly an element of the male-dynastic connection (Derichs 2013).

While studies on women and party politics have explained persuasively how and why women have underperformed in formal politics, new attention on women’s politicization through social activism has shown that besides party politics women can also assert their public roles autonomously through civil society movements, thus eschewing the male-dominated structure that has characterized political parties (Lai 2003). We can thus see women political actors as existing within—or between—two political spheres: electoral politics and civil society. Hence, while there were capable and outstanding women leaders in civil society, ranging from those advocating religious causes such as Zainah Anwar of Sisters in Islam (Perlez 2006) to those calling for electoral reform such as Maria Chin of BERSIH (Coalition for Free and Fair Elections) (Kwok 2016), these women leaders did not gain their legitimacy through electoral contests.3)

Women in civil society movements began to engage in formal or electoral politics only after 1999, when a manifesto named the Women’s Agenda for Change (WAC) was issued (Lai 2003; Martinez 2003; Tan and Ng 2003). Perhaps directly or indirectly, this strategy of considering the importance of electoral politics as the basis for women’s empowerment succeeded in raising the numerical representation of women in national and sub-national parliaments. In the 1999 GE, women for the first time comprised more than 10 percent of elected representatives in national parliament (Tan and Ng 2003, 118). Besides the WAC, another development in 1999 was the establishment of the Women’s Candidacy Initiative (WCI), in which this organization (as opposed to a political party) endorsed and fielded its own woman candidate to run on the platform of women’s issues. Although an NGO-endorsed candidate, this candidate ran under the ticket of a “friendly” political party. In this instance, the WCI saw itself as bridging women’s political participation in party politics and social activism (NGOs) (Lai 2003, 69). Tan Beng Hui and Cecilia Ng see this as a turning point in women’s social activism, a “shift from rights to representation, from the arena of informal to formal politics” (Tan and Ng 2003, 124). Others have referred to this new turn of women’s activism from civil society to electoral politics as a “definitive development” (Martinez 2003, 75). During a period of transition to a new order, such as that provided by the Reformasi movement in 1999, a broad-based coalition of women’s movements (ranging from those involved in violence against women to rights of migrant women) was able to divert some of their attention from their core purposes to an engagement with the formal political process (Stivens 2003). At this stage of “political transitioning,” gender politics was used to challenge the state but at the same time appropriated by the ruling government to act as a bulwark against its own possible defeat in the coming elections (Maznah 2002, 217). The endorsement of the WAC was said to have led to the setting up of the Ministry of Women and Family Development in 1999 and considered to be one of the most direct responses to women’s civil society activism (Saliha 2004, 151).

As to whether the post-2008 democratization climate promised more for women’s advancement, a study by Cecilia Ng (2010) on newly elected and appointed women representatives showed that there were many teething problems when women social activists crossed directly into formal politics or when they assumed their positions as elected representatives. Women had greater problems adjusting to their new roles than male activists who became politicians. Politics and political institutions today are still embedded within a gender regime characterized by a culture of masculinity that holds back new politicians, especially new young women politicians. Women state assemblypersons and local city councillors face additional discrimination due to their age and ethnic identity, in addition to intra-party competition, as they make their foray into party politics (Ng 2010, 333).

How essential, then, is it for women to enter formal politics in order for their interests to be represented? How can women’s interests or gains be maximized through formal representation? One of the bigger problems of women’s rights advocates today is trying to convince the public that both women and men stand to benefit from more equal gender relations in society. Tan and Ng emphasized early on that it would be not only fitting but necessary for women to make a direct foray into public office:

. . . in the long run, women will still need to enter the formal realm to evoke more widespread change. They cannot use their involvement in informal politics to excuse their absence in the formal sphere. Women’s groups have been involved in the amendments to and development of new laws and policies to safeguard the interests of women. (Tan and Ng 2003, 111)

An Overview of Malaysian Women’s “Descriptive” Underrepresentation in Formal Politics

The concept of descriptive representation is used here to differentiate from substantive and symbolic representations. Feminist scholarship on women in politics uses this framework of differentiated representation to acknowledge the complexity of the leadership question (Krook 2010). While descriptive representation measures how many women are elected to political office in terms of numbers, substantive representation measures how women have successfully promoted women’s issues in terms of policies and impacts. Symbolic representation, on the other hand, refers to the significance of women’s presence (or absence) in political office in influencing public (or constituents’) perceptions and opinions about women’s status in society. Essentially, it is only when all three forms of representation are fulfilled that women’s authentic political leadership can be attained.

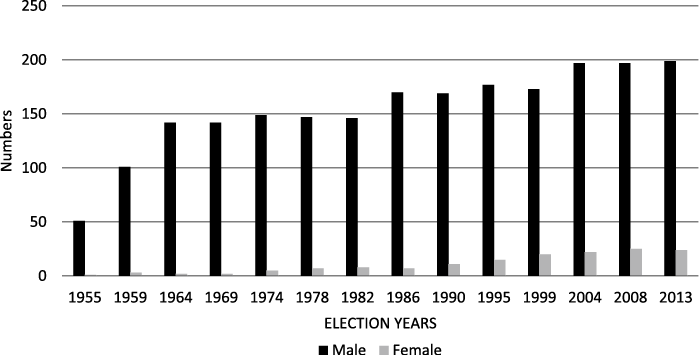

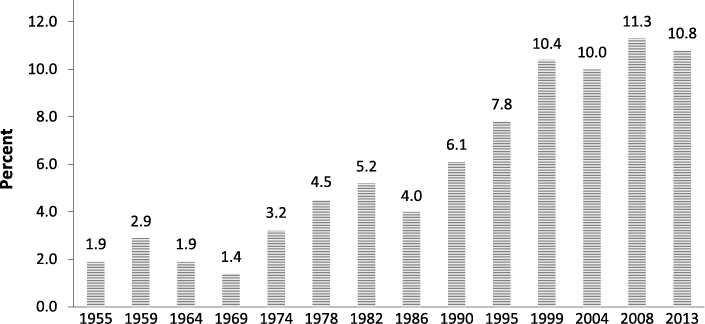

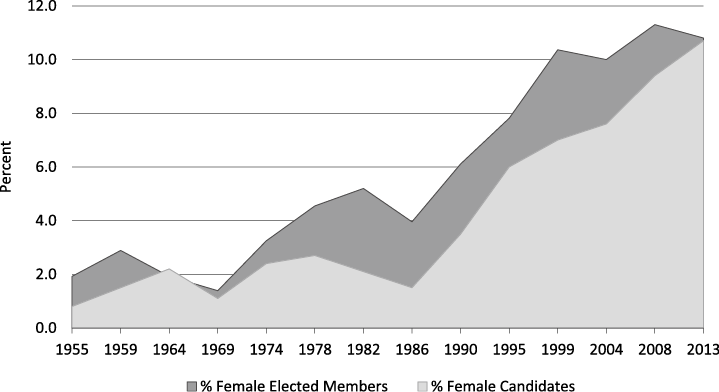

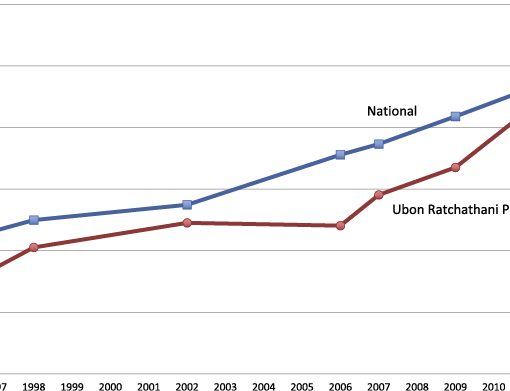

In Malaysia, the advent of women’s descriptive representation in politics improved only marginally from 1986 to 2013 (see Fig. 1). The number of women elected to parliament ranged from 1.9 percent in 1955 to 5.2 percent in 1982 (Fig. 2). It was only in the 1999 election that this figure rose above 10 percent. The highest was after the 2008 election, when the representation of female parliamentarians went up to 11.3 percent. Before the GE14, when the proportion of women’s representation rose to 14.4 percent, the highest proportion of women candidates nominated was 10.7 percent at the 2013 GE (Fig. 3). As Fig. 3shows, the percentages of women eventually elected in successive GE years were actually higher than their percentages at nomination. Hence, increasing the number of women candidates may result in an increase in the numbers elected.

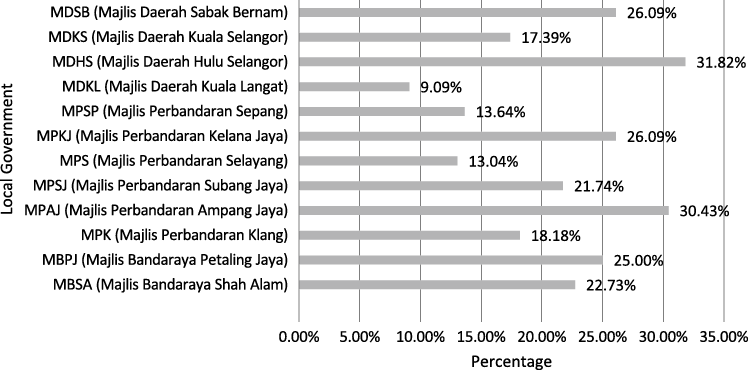

Even at the level of local government, in which women are nominated rather than elected, ruling political parties do not attempt to increase the number of women’s representation. Selangor, though ruled by the PR (Pakatan Rakyat—People’s Coalition) government with the highest number of women parliamentarians, managed to have only one local council almost reaching the one-third representation mark (32 percent) for women (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1 Members of Parliament by Sex, Malaysia 1955–2013

Sources: 1955 to 2008 figures from Tan (2011, 89); 2013 figures from Sharifah (2013, 5).

Fig. 2 Percentage of Female Elected Members of Parliament

Sources: 1955 to 2008 figures from Tan (2011, 89); 2013 figure from Sharifah (2013, 5).

Fig. 3 Percentage of Female Candidates and Female Elected Members of Parliament, by Election Years, 1955–2013

Sources: 1955 to 2008 figures from Tan (2011, 89); 2013 figures from Sharifah (2013, 5).

Fig. 4 Percentage of Females in Local Governments of Selangor, 2015

Source: Information provided by Selangor local government offices.

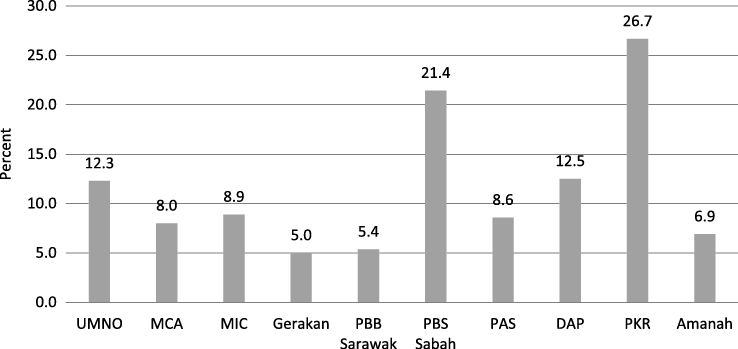

The representation of women leaders in each party’s central committee or its highest governing body (Fig. 5) is also evidence of the gender political gap. In 2017 women’s representation at the highest leadership position was highest within PKR, at 26.7 percent, while the lowest was in Gerakan, with only 5 percent of women in its highest governing committee. It appears that no concerted effort is being made to increase women’s representation within internal party structures.

Fig. 5 Percentage of Women Representatives in Highest Governing Committee within Major Political Parties* in Malaysia, 2017

Source: Data compiled from information found on the official website of each political party.

Notes: * Acronyms and names of Political Parties:

UMNO: United Malays National Organisation, MCA: Malaysian Chinese Association, MIC: Malaysian Indian Congress, PBB Sarawak: Indigenous Party of Sarawak, PBS Sabah: United Party Sabah, PAS: Islamic Party of Malaysia, DAP: Democratic Action Party, PKR: People’s Justice Party

Collaboration, Clientelism, and Coalition Building as a New Nexus of Women’s Political Participation

Given the persistence of women’s underrepresentation in Malaysia’s parliaments, the more tangible ground-level specificities of women’s restricted entry into formal politics need to be better understood. The collaboration of interest groups with political parties, the practice of clientelism, and the demands and constraints of coalition building as inhibitors or supporters of women’s political participation are some of the factors that are explored in this article.

The notion of collaboration between political parties and interest groups or NGOs involves the relationship between actors in formal and non-formal political spheres. It is particularly important as a site of study during periods of political transition (Otjes and Rasmussen 2017). Ever since the advent of the opposition coalition or the PR, with its capture of five state governments in the 2008 GE,4) more civil society actors and interest groups have collaborated with the PR governments in formulating policies and building institutions. In fact, among women PR candidates who were elected into office, many were previously members of civil society and social movements, hence making a cross-collaboration between parties and interest groups almost inevitable (Ng 2012).

Coalition building refers to multiparty governance and is another variable used to gauge women’s formalization in politics. In Malaysia, what has existed since 2008 is the formation of a dual-coalition involving the coalition of the ruling BN and the opposition coalition PR. The latter denied BN of its two-thirds majority in parliament and captured five state governments during the 2008 GE. In Malaysia UMNO has remained resilient, through various means, as the single largest dominant party in the system in terms of membership, seats contested and won, as well as magnitude of mobilization resources (Gomez 2016). In the GE14 the BN coalition contested against the former PR coalition, which assumed a new name for this election, Pakatan Harapan (PH). The GE14 was a historic election as PH successfully ended the 61-year rule of a government under BN that had not lost a single election since Malaysia’s independence from British colonialism.

Cobbling together multiparty coalitions is inherently tenuous and fragile, as each party within the coalition has different goals, identities, and founding principles, which occasionally clash. To remain together, coalitions try to converge along some centrist lines. Observing these dynamics before the onset of the GE14, this article examines whether centrist policies favoring an increase in women’s candidacy were adopted at all.

Another central idea brought into this study is the concept of clientelism, which will be applied in the understanding of women’s marginalization or visibilization in formal politics. The concept of clientelism is derived from the original notion of patron-client relations in politics, in which an asymetrical, though mutually beneficial, relationship is built between political patrons and their clients. In exchange for protection and benefits from the patron, the client provides support or services. Elements of this relationship include reciprocity, affectivity, and personalization (Lemarchand and Legg 1972, 151; Scott 1972, 92; Kaufman 1974, 285). A more wide-ranging concept of clientelism as applied to politics and political networks could also include bonds between people, which can be long-lasting (Tomsa and Ufen 2013, 5). Clientelism is underscored by elements of iteration, status inequality, and reciprocity (ibid., 6). There is evidence that Southeast Asian political culture is based largely on clientelism, in which service orientation and pesonalization are key to winning the support of voters (Bjarnegard 2013; Teehankee 2013).

Features of personalized politics based on patron-client relations include “a contingent relationship between politicians and voters, sometimes mediated by brokers, in which concrete benefits are exchanged for votes” (Bustikova and Corduneanu-Huci 2017, 278). This article examines the extent to which women’s entry and resilience in politics depend on the exchange of support between patrons giving incentives and clients returning their votes.

The postulation of this study is that as electoral competition in Malaysia becomes more extensively charted by the collaboration between formal and non-formal political actors, the entrenchment of clientelist politics for voter support, and the strengthening of coalition building, women’s prospects of getting into political office will face two possible outcomes, both positive and negative for their increased representation in formal politics. The political transition brought about by a more competitive dual-coalition electoral contest may provide a wide window of opportunity for interest groups to push and advocate for more innovative measures and policies for women’s formal political participation and representation. On the other hand, the tenuous and contentious nature of coalition and clientelist politics may continue to obstruct women’s entry into formal politics.

A Newer Dawn of Collaboration: Institution Building

It is said that the collaboration between political parties and interest groups can be a cornerstone of democracy (Otjes and Rasmussen 2017, 96). As noted earlier, events around the 1999 GE propelled women’s issues and the gender card in politics to take on a greater significance than at any time before. There was an increase in women’s candidacy from 25 in the 1995 GE to 30 in the 1999 GE. The eruption of Reformasi politics played a major role in upsetting BN’s hitherto unassailable political dominance (Loh and Saravanamuttu 2003).

In relation to women’s prominence in formal politics, there were several reasons why the 1999 GE provided new grounds for this change. The first had to do with the entry of Wan Azizah, the wife of Anwar Ibrahim, as an icon of the opposition forces. She became the leader of the newly formed opposition party, PKR, and quickly became a popular figure in the Reformasi movement triggered by the crisis over Anwar’s sacking as deputy prime minister.

The 1999 GE, held soon after Reformasi, was historic in that it was the first time in the nation’s history that women comprised more than 10 percent of elected Members of Parliament. The four women opposition leaders made up 9 percent of the 45 opposition seats, while women government representatives won 11 percent of the 148 seats held by BN.

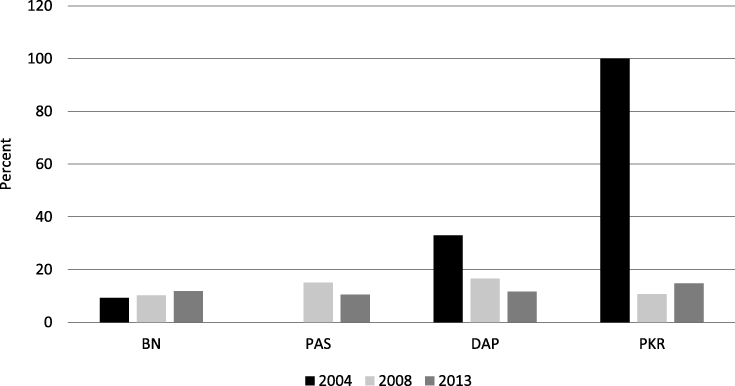

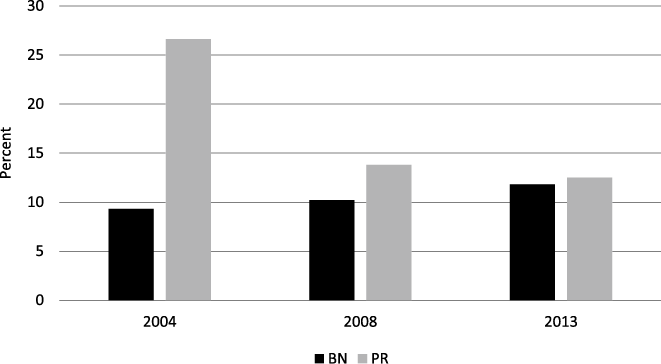

Fig. 6 notes the shifting party dynamics in the 2004, 2008, and 2013 GEs. In 2004 PAS did not field any women candidates at the parliamentary level. However, by 2008 it had three of its women candidates elected to parliament. The DAP (Democratic Action Party) had its best record of women candidates elected in 2004, although the party as a whole did badly that year. PKR’s sole seat in 2004 was won by its president, Wan Azizah. It was only in 2008 that the PR coalition showed its best performance, but this was not necessarily reflected in the proportion of seats won by women candidates. In 2013 PKR women candidates who were elected comprised 14.8 percent of party seats, DAP women 11.7 percent, and PAS women 10.5 percent. There was actually an overall drop in women’s representation in the PR coalition in the 2013 GE as compared to the 2008 GE (Fig. 7). On the other hand, the proportion of women’s representation from BN seemed to be somewhat consistent in the three GEs. Comparing the two GEs of 2008 and 2013, women’s election success rate was higher in the former, when 52.5 percent of women candidates were elected as opposed to 48.7 percent in 2013 (Malay Mail Online 2014a).

Fig. 6 ercentage of Women Elected out of Total Elected within Each Political Party, 2004 to 2013 GEs

Sources: Various secondary sources.

Fig. 7 Percentage of Women Representatives Elected, BN versus PR Coalitions, 2004 to 2013 Malaysian GEs

Sources: Various secondary sources.

Some gains had undoubtedly been achieved for women as soon as the PR coalition successfully captured the two urban states of Penang and Selangor. The DAP-led state government in Penang quickly approved the setting up of the Penang Women’s Development Corporation (PWDC) as a statutory body directly under the state government. The PWDC was formed on January 2, 2012. Its board of directors has 11 members, 5 of whom are elected representatives from political parties within the PR. The setting up of this institution was the result of some four years of collaboration between the state, NGOs, and a university research center after the PR-led government took over from the incumbent BN in 2008. In the 2012 budget the chief minister tripled the previous year’s allocation for women’s development. One of the first projects that the interim group started was the Gender Responsive Budgeting (GRB) project for Penang. Universiti Sains Malaysia’s Women’s Development Research Centre, KANITA, worked with the state and local governments—the Penang Island Municipal Council (MPPP) and the Seberang Perai Municipal Council (MPSP)—to initiate and pilot the GRB program. The state government committed RM200,000 annually, with the MPSP matching this funding with an additional RM200,000 annually for a three-year pilot scheme, while the MPPP provided RM63,000 annually to this project. The GRB three-year pilot involving partnerships with MPSP, MPPP, and the community eventually became PWDC’s flagship program, making this one of the first successful collaborations between women’s interest groups, political parties, and local governments (Ng 2012).

By 2016 the GRB was referred to as the Gender Responsive and Participatory Budgeting program, with the addition of the “participatory” component. This was due to the active involvement of the local town councils in the program. The PWDC website lists the setting up of 14 projects involving 6,775 people. Another project, the Women’s Brigade, involved clients at the sub-local level, with the participation of 2,757 women. In 2016 the PWDC initiated a new project on electoral reform to increase women’s participation in formal politics. One proposal was to seek measures to raise the participation of women to at least 30 percent of electoral seats, an initiative that will be discussed in greater detail later in this article.

In the case of the Selangor state government, the Institut Wanita Berdaya (IWB, Women’s Empowerment Institute) was formally launched in October 2017. Before this, in 2014, the state had set up a program that fulfilled both the goals of women’s empowerment as well as building a base of grassroots women in exchange for their political support. It established 56 Women’s Empowerment Centres or Pusat Wanita Berdaya (PWB), one in each parliamentary constituency. For each of the centers, a coordinator was hired and paid a monthly salary to run activities within their designated area. An annual allocation of RM30,000 was given for each constituency to run programs that would involve women’s participation. In January 2017 the Selangor government went a step further in allocating RM1 million toward the setting up of a think tank for women’s advancement. An additional RM9 million was allocated in the 2017 budget for running women’s programs in the state. When the IWB was launched in 2017, the Selangor Women’s Policy and Plan of Action was also concurrently launched.5)

In the Penang and Selangor cases, the collaboration successfully culminated in the building of social institutions for advancing women’s rights and interests. The other area of collaboration was policy reform. In 2016 the PWDC spearheaded a project on Gender in Electoral Reform. A successful conference was held in August 2016 to deliberate on how variations on electoral systems could make a difference in women’s descriptive and substantive participation in formal politics (PWDC 2016). Speakers from New Zealand, Indonesia, and Germany (countries that had reformed their electoral systems for more inclusive representation) were invited to share their experiences. The main electoral systems being compared were the first-past-the-post (FPTP) and mixed member proportional (MMP) systems. The former is practiced in Malaysia, while the latter is used in New Zealand and Germany. What emerged from this meeting was that the most viable option to fast-track women’s representation would be to institute a form of gender quota in tandem with the MMP system (ibid., 17–18). According to Dr. Wong Chin Huat, one of the speakers at the conference, if Malaysia’s electoral system was changed to the MMP the 222 seats the Malaysian Parliament had could be split between parliamentarians representing geographical constituencies and those representing the party list, the latter being representatives that would take up interests and issues-based concerns. This was where the party list may make an allowance for a gender quota. The MMP system would also safeguard against manipulation by the incumbent through gerrymandering, malapportionment, and voter-transfer exercises. Removing these obstacles would help to get more women into politics (ibid.).

This advocacy project of increasing the representation of women in politics through electoral reform by way of a gender-quota system is one of the most concrete proposals to have emerged on this issue. Some aspects of it are feasible, while others are not. For example, it would be infeasible for Penang state to implement it, as this change would require constitutional and legislative changes. Articles 116 and 117 of the constitution would have to be amended. Legislative changes would also include amending the Election Act 1959. But the momentum for seeing through the reforms toward increasing women’s political representation is picking up. In March 2017 a public forum was held by the Penang Institute titled “Women and Inclusive Politics Forum: State Assemblies and Additional Seats for Women.” Wong presented several detailed and refined options to get more women into political office. A significant suggestion that came out from this forum was that it would be possible to get more nominated women parliamentarians through a quota system that would require one of the following: (1) voluntary quota list implemented at the party level for internal and external elections, (2) retention of Malaysia’s FPTP system with 30 percent women’s quota at the candidacy level, (3) amendment to the national constitution to adopt the MMP system with both constituency seats and party list seats, (4) amendments to state constitutions to allow individual states to include a set proportion of women-only additional seats in the state assembly (Wong 2017).

The momentum and campaign for pushing increased women’s representation in formal politics through the quota or reserved seats system were covered by the media (Alyaa 2017; Maznah 2017) and have formed the basis of the pledge by the opposition coalition PH to ensure 30 percent women’s representation in public and political office (Malaysian Insight 2017).

Clientelist Politics and Incentivizing Women’s Support

In my recent study of Penang and Selangor, the two states with opposition or PR governments, elected women leaders exuded more confidence than during their earlier years described by Ng (2010). What changed? My observation was that women leaders were by then able to use the advantage of state office to sustain and build their constituent base due to their political legitimacy and access to resources, all of which are necessary to cultivate some form of patronage in exchange for clientelist support.

Women’s entry and sustained involvement in formal politics can be related to their adoption of a form of women-centric clientelistic politics. Previously this involved the simple though asymmetrical exchange of money-for-votes type of practice, with politicians benefiting more in terms of electoral gains than voters gaining short-term tangible rewards. Newer forms of clientelist politics are, however, seen as a two-sided mutually beneficial relationship involving protection in exchange for support, or jobs in exchange for votes, or more power (to the giver) in exchange for allegiance (by the taker) (Kopecky and Spirova 2011). Elements of affect and intimacy are also built in, giving politics its personal touch (Rivoal 2014). For a long time the opposition parties in Malaysia did not have the opportunity to carry out politics in this way. Support for “opposition” causes would have to depend on mass organizations and the degree to which particular ideological stances could resonate with particular interest groups. On the other hand, ruling parties, notably BN, have always had access to state power and its resources in the form of funds, jobs, committees, boards, and other benefits in exchange for support.

Essentially it is still the tried and tested ability to have a clientelist base that assures one of political support and loyalty. Clientelism that works in women’s favor will allow them to break the monopoly of male gatekeeping within political parties. Since male gatekeeping is usually exercised when it comes to choice for candidacy, it is necessary to have more women leaders who can displace this male monopoly:

. . . gatekeepers are more likely to directly recruit and promote people like themselves. Studies have associated the presence of female party elites with more female candidates because women are more likely to encourage other women to become active in politics by favoring candidates with female traits or by supporting policies to increase female candidates. (Cheng and Tavits 2011, 461)

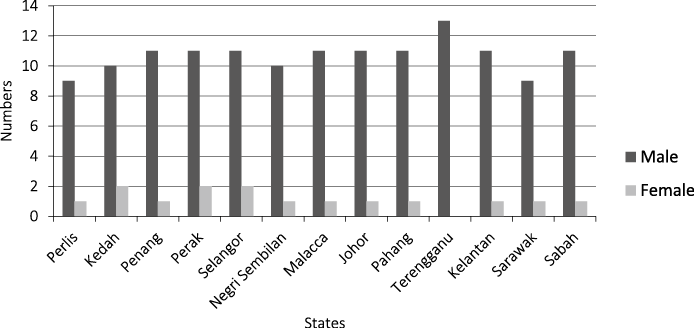

But to what extent can clientelism overcome male gatekeeping and barriers such as the containerization of women within the “women’s wings” (as described by Derichs 2013, 304)? So far the capacity for women to overcome the twin obstacles of gatekeeping and containerization has been limited, and this situation will remain unless more women are in office and have access to measures that can enable the clientelist exchange. It is a chicken-and-egg situation where more women will beget more women. At the moment, the smaller numbers of women in federal and state cabinets mean that fewer women will have the capacity to utilize the clientelistic approach. For example, at the national level few women get elected as parliamentary representatives. This leads to a small number of women being appointed as cabinet ministers. Elections at state levels have also turned out fewer women representatives in state assemblies, with most states having only one woman state cabinet minister (state executive member); it is only in the states of Kedah, Perak, and Selangor that there are two women state ministers (Fig. 8). There are no local councils (city government) with more than a third (33 percent) of women on their boards, with the overall national percentage of women on local council boards being 13.6 percent (Wong 2017).

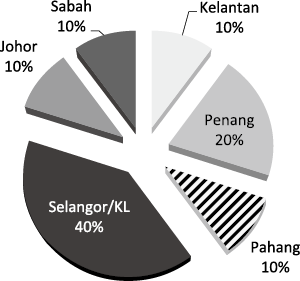

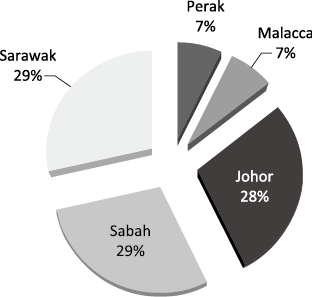

One way to estimate how clientelism can work in the current situation of political alignment in Malaysia is to examine the breakdown of women representatives by state (Figs. 9 and Fig. 10). There is apparently a positive correlation between the number of seats that coalitions in each state are able to win and the number of women representatives that these states have. The two opposition states of Selangor and Penang have the highest proportion of women Members of Parliament—40 percent and 20 percent respectively. Similarly, the strongest wins for the BN coalition in 2017 were the three states of Johor, Sarawak, and Sabah with about 28 percent to 29 percent women Members of Parliament in all three states. It is not clear how this happened, with the “women-friendly” states of Penang and Selangor for the PR coalition and Sabah, Sarawak, and Johore for the BN coalition. But the circumstances of their electoral wins may provide some advantage when it comes to more women being elected to the state cabinets. The more that women have access to government resources the more they will be able to cultivate their patron-client relationships in these states. The key would be for women to use these resources to cultivate more potential women candidates, as it has been demonstrated elsewhere that the presence of more women leaders leads to more potential women leaders. A study in Canada found that constituencies with a history of women candidates in a particular district are considered women-friendly and have paved the way for the nomination of more women candidates in subsequent elections (Cheng and Tavits 2011, 467). The mechanics of why this occurs has not been extensively explored. This paper suggests that clientelism may play a role, particularly through the use of incentives such as the targeting of specific women constituents for direct benefits and cash transfers.

Fig. 9 Opposition Women MPs, by State, 13th Parliament, 2017

Source: Portal Rasmi Parlimen Malaysia.

Fig. 10 Government Women MPs, by State, 13th Parliament, 2017

Source: Portal Rasmi Parlimen Malaysia.

Accentuating and increasing benefits and incentives for women at the everyday, palpable level can become one of the key strategies for winning women voters in Malaysia today. Before the culmination of the GE14, various programs were implemented by national and state governments to achieve the goal of uplifting the livelihoods of women. Women have now become a strategic target for benefits in the form of purposeful or conditional cash transfers by the state. The Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development (MWFCD) has various programs for the very poor. One poverty program coordinated by the MWFCD is called 1Azam.6) There were at least 3,737 programs listed on the e-portal set up in various states, covering issues from income generation to wheelchair gifts, from hemodialysis treatment to motivational courses.7)

In the GE13 “single mothers” as a segment of targeted beneficiaries allegedly numbered 831,860. They were promised direct cash payment, legal insurance schemes, and housing allocation by the incumbent ruling party and were referred to as a “fixed deposit” or vote bank by the prime minister (Rozanna Latiff 2013). It seemed that this campaign promise had been made good. By 2016 the MWFCD had set up One-Stop Centres on a nationwide scale to cater to the needs of single mothers. In conjunction with this, a cabinet-approved National Single Mothers Empowerment Plan was launched in early 2016. The plan included providing government aid to single mothers by equipping them with income-generating skills (Halim 2016).

The Selangor state government identified 12 groups of women as targets for empowerment: housewives, working women and women in the informal sector, single mothers, disabled women, elderly women, young women, teenage girls, Orang Asli, migrants, industrial workers, women in poverty, and women in the rural and plantation sectors.8) Women were the beneficiaries of at least eight women-targeted programs: the setting up of constituency-based Women’s Empowerment Centres (PWB, Pusat Wanita Berdaya), free mammograms, enhanced One-Stop Crisis Centres, benefits for single mothers, Hijrah microcredit scheme, childcare subsidy scheme, free training courses for those intending to set up childcare centers, and additional parental leave provisions for employees of Selangor public services.9) A special section in the 2017 Budget speech delivered by the chief minister emphasized the state’s initiatives as being “gender inclusive.” As for Selangor’s microcredit program, Hijrah, the chief minister mentioned that 63.6 percent of its 25,466 participants were women. Sixty-five percent of the Selangor Scholarship Scheme recipients were also female. The chief minister emphasized that state agencies under his charge were focusing on appointing women in senior leadership positions. The budget speech made a special mention of women’s achievement in decision-making positions:

Selangor has a woman for the position of District Officer and two as heads of Local Authorities. Meanwhile, five State agencies are led by women. In the latest development, the newly appointed General Manager and Deputy General Manager of PKNS (Perbadanan Kemajuan Negeri Selangor—Selangor State Development Corporation—) are women who are highly competent and have a wealth of experience in the property industry. (Selangor State Assembly 2016, 55)

The Penang state government also identified its main vulnerable constituencies as falling under the social welfare category.10) There were six of them, with women falling under two categories: “single mothers” and “golden mothers.” Eligible beneficiaries were required to register with the government online through an app called AppsSejahtera. The common requirement for cash benefits was that candidates must be resident and registered voters in the state of Penang. The definition of single mothers under the Penang program is more general than the one adopted by the Malaysian cabinet, the requirement being that the beneficiary must have at least one child and not have remarried. In order to qualify under the golden mother category, a woman must be below 60 years old, married, and without a fixed income. It is difficult to say whether reaching out to the most vulnerable women will make women voters more inclined to vote for women leaders. It is not clear what the delivery mechanism is like, but a personal touch in the handing out of benefits is to be expected. Women representatives apparently have to make their presence and visibility felt among voters on social occasions such as government-organized get-togethers, weddings, ceremonial feasts (kenduri), and even funerals. If more women leaders had such resources, there would be a higher chance of their being involved in welfare delivery programs that deal directly with women, children, and families and hence of being eventually fielded as credible candidates in elections.

Incentivizing women’s support for women’s agenda in electoral politics was institutionalized through the setting up of state-funded women’s development and empowerment institutions. As detailed in the preceding section, the setting up of the PWDC in 2012 and the IWB in 2017 in Penang and Selangor respectively provided an important avenue for women politicians to cultivate their clientelist base of women in support of women’s issues and rights.

Coalition Politics: Not Always a Middle Ground Advantage for Women

The necessity for coalition politics to increase the chances of victory in Malaysia’s last three general elections (2008, 2013, and 2018) played a direct role in determining women’s recent entry and participation in formal politics. In any coalition a diversity of political parties inevitably steers toward a middle ground for consensus, which has been observed to have some advantages for women candidates. For the opposition parties, the first successful coalition building occurred during the 2008 GE. But in 2004, PAS, being in an informal opposition coalition, had started to relax its women’s candidacy policy. In the 2004 GE the party allowed women to contest, 35 years after it had last fielded its first woman candidate, who won in the 1969 election. It was the politics of Reformasi and its opposition of UMNO that created an opening for PAS’s party women at this time. In 2004, 10 women were fielded and two won in the Kelantan state election. Public attention and pressure eventually led to one of the women being appointed to the state cabinet and as vice-chairperson of the Women, Youth and Sports portfolio (Ng et al. 2007, 97). In the 2008 and 2013 GEs PAS also sidelined its “Islamic state” agenda in place of the “welfare state” (Negara Kebajikan) agenda. At the same time, the DAP became more inclusive of Malays by restraining any criticism against PAS’s other more thorny agenda of wanting to institute the Hudud or Islamic Religious Punishment law. The DAP also embraced gender reforms and fielded many women candidates in the 2004, 2008, and 2013 GEs. In fact, the proportion of its women candidates elected in the 2004 GE was much higher than in the 2008 or 2013 GE. PKR would always have to profile itself as more moderate, or taking a more centrist line, than the two older parties (DAP and PAS). Being the newest party in the coalition, it could not be seen to be inheriting the past baggage of an ethnic or religious agenda. Hence, it went along with its moderate Islamist stance and multiculturalist identity. PKR also had an advantage in having Anwar’s wife as its first female president. Anwar’s daughter, Nurul Izzah, also assumed a leadership role within the party and became an icon for young Malays, especially young women, at the onset of Reformasi in 1999.

In the early stages, the opposition coalition concentrated on finding a middle ground for inter-party solidarity. The professed policies of the opposition parties were all centrist and moderate in nature. Political leaders were not afraid to propound novel policy reforms, including gender reforms. This was what was known as the moderation policy on gender, which would be part of an ideological renewal strategy by political parties keen to join forces with other parties in order to have an advantage in elections. Elsewhere, the case of the British Conservative Party teaming up with the Liberal Party in the UK had illustrated this tendency (Bryson and Heppell 2010; Campbell and Childs 2015). At the level of rhetoric and political campaigning, gender equality would still be an abstract ideal, yet to be subjected to any action plan and hence easy to promote (Kokkonen and Wängnerud 2016).

In Malaysia, the PR coalition progressively rose in political stature and governance capability. This began with its denial of the two-thirds majority to BN in the 2008 GE, then progressed to its winning the popular vote in the 2013 GE. Finally, under its renewed name and configured coalition partners, PH won the election in 2018.

Before the GE14, the most important issue that led to the split in the PR coalition was the disagreement over the passage of an Islamic law, or the Hudud Bill (Islamic Punishment Bill). The other issue of contention was the question of women’s leadership.

The contention over women’s leadership was precipitated by the stepping down of Selangor Chief Minister Khalid Ibrahim due to party pressure in 2014. The PR coalition put up Wan Azizah, the party president of PKR, as its preferred choice to replace Khalid. However, one faction of the PR—PAS—favored the party’s male deputy president, Azmin Ali. The ultimate power to approve the nomination was with the monarch of the state, the Sultan of Selangor, who eventually chose Azmin Ali to head the state government.

In the above circumstance, the women’s wings of the three parties within the coalition tried to stand together in supporting the appointment of the first female state chief minister of the country. However, only the women leaders of PKR and the DAP stuck to this stance while the women’s wing of PAS withdrew its endorsement. The head of PAS’s women’s wing claimed that the statement was purportedly “circulated before I had time to go through and signed it . . . our loyalty is only to the decision of the federal PAS” (Malay Mail Online 2014b). Later, a formal statement was issued by the deputy chief of the Federal Territory branch of PAS’s women’s wing, claiming that Wan Azizah’s poor leadership was the reason behind their rejection of her nomination. This was apparently in reaction to the DAP women’s chief’s criticism of the PAS president for breaking up the PR, as a male, by accusing Wan Azizah of being unsuitable for the job (Malay Mail Online 2014c). This disagreement over Wan Azizah as the choice for heading the Selangor state government was only one of a series of issues that widened the rift between the political parties, but it did blemish the coalition’s vision of promoting gender equality and empowerment in politics.

The other, and ultimately main, issue that led to the breakup of opposition coalition politics was the passage of the Hudud Bill, a law that could enable the enforcement of the sharia provisions of capital punishment at the state level. In 2015 the Syariah Criminal Code was passed at the Kelantan state assembly, followed by the tabling of a private member’s bill in parliament to remove legal obstacles for the Hudud to be enforced (Palansamy 2015). The fallout of all this was the formation of a splinter party from PAS, the Parti Amanah Negara (Amanah), and the formation of a new coalition named Pakatan Harapan (PH). The latter, set up in September 2015, was designed to exclude PAS from the coalition (Shazwan 2015). In the case of PAS leaving the PR coalition, it seemed that the former would rather sacrifice the coalition’s common policy goals than risk losing the support of its own predominantly Islamic electorate, comprising mainly those who supported the Islamization agenda for the nation (central to which was the passage of the divisive Hudud Bill). Like coalitions elsewhere, this was a case of diverse parties unable to operate together, with some not wanting to compromise on either their narrow campaign promises or their controversial policy goals (Fortunato 2017, 18).

Before the election of the new government in the GE14 under the PH coalition, PAS and the DAP controlled the state governments of Kelantan and Penang respectively. It seemed that they would be the most unlikely to become coalition partners, one party being predominantly Malay Muslim and the other predominantly Chinese, PAS being more established on the rural eastern side of the peninsula and the DAP on its urbanized western side. Perhaps their relative comfort and autonomy of having equal state powers led to disruptions in their earlier professed policies of moderation. PAS left the coalition ostensibly to pursue its more hardline or “authentic” Islamist stance. The DAP, on the other hand, decided to focus on keeping and strengthening its Chinese support base while tempering the fallout with PAS by placating its more moderate Malay constituents. Where would all this leave reforms for gender equality in political representation?

Interestingly, in 2015 a study by the social media research firm Politweet on Malaysia’s 18 million Facebook users found that women had lost interest in the DAP. The overwhelming interest in the DAP (74.4 percent) came from males, which was much higher than the interest shown by males in other political parties (58 percent). Interest in the DAP among female Facebook users dropped from 1.5 million users in April to 1 million in July (Malay Mail Online 2015). It would be speculative to assert that this could have been because the DAP had yet to have an effective message or brand that could appeal to young women. Nevertheless, the DAP achieved success with its women candidates in the GE14 with a 100 percent success rate—all the women who were fielded were voted in. However, it cannot be said that the success of DAP’s women candidates was largely due to the support of women voters, as there was a general “tsunami” of a majority of voters exerting their swing vote for a new government regardless of ethnicity or gender (Malaysiakini Team 2018).

As to the question of more long-term reform, such as ensuring the 30 percent quota for women’s representation in decision-making positions, it is not clear whether the DAP was fully committed to pushing this through to the end. The party gave the impression that it would be giving women a “New Deal.” However, it is difficult to interpret what was meant by this phrase in a 2016 speech by the party’s secretary general: “a 30% gender quota for Central Executive Committee (CEC) elections” (Lim 2016). Did this mean that 30 percent of seats within the CEC would be contested only by women? Or could it be that 30 percent of nominations in the contest for CEC seats had to be set aside for women? So far, this New Deal has not been tested as there have been no CEC elections since 2013. As for PKR, it also claimed rather widely and generally that its crucial leadership positions would be reserved for women: the 30 percent requirement supposedly mandated by the party’s constitution. In fact, this stipulation is only contained as a resolution made at the party’s 2014 convention and now listed as the party’s “principles of struggles” aiming to empower women to achieve equality in leadership and decision making, with at least 30 percent involvement as a way of guaranteeing their rights and interests.11) The ambivalent overture made by both parties on their commitment to women’s 30 percent representation seemed to have provided a safeguard against giving in too much to the gender equality agenda lest this override the parties’ other distributive concerns around ethnicity, religion, and regionalism.

The question now is whether the coalitions on both sides, BN and PH, are still open to reforms on gender representation. Now that the 14th GE has put PH in power, more attention will be focused on its gender representativeness pledge. During the campaign period for the GE14, PH did actually proffer a platform of electoral reform for increased women’s representation. The ruling government then (BN) also did not overlook women as an important constituency. Early in 2017 the deputy prime minister announced that his government would see through the 30 percent quota for women: “I will find a way so that this 30 percent request is achieved. Enough of talking rhetorically” (Malaysiakini 2017). Even before this, during the campaign period of the 13th GE, the prime minister recognized the significance of women’s votes, particularly among vulnerable women. The category of women grouped under “single mothers” was viewed as a “fixed deposit” by Prime Minister Najib Razak, given their loyalty to the coalition. He said, “I want to do more for single mothers but we have to cross a small bridge first . . . a bridge that ends on May 5 (polling day)” (Rozanna 2013).

In September 2015 then Prime Minister Najib Razak announced the launch of the national action plan to empower single mothers at a global leaders meeting on gender equality and women’s empowerment at the UN headquarters, New York. Najib said Malaysia had set a target of increasing its female labor participation rate from 54 percent the previous year to 59 percent by 2020. The government also launched a Career Comeback Programme to provide opportunities for women to return to work after leaving the workforce (Malay Mail Online 2015). Other initiatives to brand BN as family- and women-friendly included the passage of the Sexual Offences against Children Bill in early April 2017. This bill was initiated by Azalina Othman Said, minister in the Prime Minister’s Department in charge of law, who once headed the Young Women’s wing of UMNO (Puteri UMNO). However, the issue of child marriage was not covered under this bill, which has led opposition women politicians to charge that the bill was inadequate. When the bill was proposed, MP Teo Nie Ching wanted an age limit for marriage as there was—and still is—a contradiction in the legal system: under civil law the minimum age for marriage is 16, while the proposed bill defined children as below 18 years old (Kumar 2017). All these initiatives and debates among women MPs was a demonstration of substantive representation, or women’s representation going beyond numbers, as what was needed was quality and substantive engagement by women lawmakers when it came to issues such as the above. Whenever issues affecting women, family, and children came up in parliament, experience had shown that it was largely women politicians who would—or could—competently participate in the parliamentary debates. Bringing these examples to the fore could sway voters’ consciousness about the need for more women’s representation in parliament. Both the numbers and the quality of women representatives will be the necessary factor that could lead to a greater scrutiny of issues and principles around gender rights and justice.

Conclusion

In examining some of the more direct processes hampering women’s entry and participation in formal politics, this article has identified newer dynamics in determining women’s visible representation. Three factors have converged to affect women’s political involvement: (1) collaboration and exchange between women’s civil society interest groups and formal state political actors in building institutions for change for women; (2) the opportunities among women politicians, once given more strategic governing positions, to cultivate clientelist and patronage politics in order to retain and expand their constituent support base; and (3) the need to maintain a cohesive multiparty coalition by advocating centrist and middle-ground policies that are inclusive of women’s greater political participation and ultimately strategic as an electoral advantage. These three factors seem to have facilitated opportunities for women to gain a foothold in political leadership.

Tied to all of the above have also been long-term plans to institute and advocate for gender representation through electoral reform. This initiative, of reforming the electoral process to the advantage of women’s representation, had been made possible before the start of the GE14 by the control of resources by governments from the PR coalition. The state governments of Penang and Selangor were particularly active in collaborating with women’s interest groups to support advocacy and the setting up of institutions that provided material and social incentives to women. Women’s induction into clientelist politics had thus allowed for a slight chipping away of a male monopoly in gatekeeping functions within political parties. Newer strategies to reform electoral laws through reserved seats and quotas allowing for gender representativeness can also be seen as one of the dividends in the political party–civil society collaborative enterprise.

The competitive mobilization for voter support by the BN and PR coalitions resulted in women becoming an important target of patronage. However, as discussed earlier, the ability of political coalitions to remain within a course of centrist, moderate, inclusive, and women-friendly agendas and policies was a constant challenge. Whenever this ability to stay centrist was strained, women’s cause for equality and representation became one of the first casualties. The practice of clientelist and coalition politics tended to be played out within an ethnicized landscape, resulting in gender rights having to compete with regional and religious causes among the general electorate. Priorities for electoral reform in women’s favor thus oscillated between being at the margins or at the center of political strategizing, bargaining, and negotiation. The experience of the GE14 showed that despite the groundwork done to increase women’s candidacy in the election, women made up only 10.75 percent of candidates fielded for the state seats, while for parliamentary seats only 75 of 719 contestants—or 10.43 percent—were women.

The best option is still for women to lobby for gender-quota legislation while not losing sight of complementary efforts, such as building women’s leadership capacity so that meritocracy is also applied as a principle in the selection of women candidates. It is necessary to continually institute internal party reforms and improve the quality of women’s substantive representation, as has been done by other successful democracies. In these more advanced democracies, the gender-quota route was adopted to ensure that women would not have to wait a few more decades before occupying the spaces of politics and governance (Yoon and Shin 2015; O’Brien and Rickne 2016).

Accepted: June 29, 2018

References

Allen, Nathan W. 2015. Clientelism and the Personal Vote in Indonesia. Electoral Studies 37: 73–85.

Alyaa Azhar. 2017. Women-Only Electoral Seats: A Solution to Gender Gap in Policy Making? Malaysiakini. July 26. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/389822, accessed October 17, 2017.

Bjarnegard, Elin. 2013. Who’s the Perfect Politician? Clientelism as a Determining Feature of Thai Politics. In Party Politics in Southeast Asia: Clientelism and Electoral Competition in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines, edited by Dirk Tomsa and Andreas Ufen, pp. 142–162. London: Routledge.

Bryson, Valerie; and Heppell, Timothy. 2010. Conservatism and Feminism: The Case of the British Conservative Party. Journal of Political Ideologies 15(1): 31–50.

Bustikova, Lenka; and Corduneanu-Huci, Cristina. 2017. Patronage, Trust and State Capacity: The Historical Trajectories of Clientelism. World Politics 69(2): 277–326.

Campbell, Rosie; and Childs, Sarah. 2015. Conservatism, Feminisation and the Representation of Women in UK Politics. British Politics 10(2): 148–168.

Cheng, Christine; and Tavits, Margit. 2011. Informal Influences in Selecting Female Political Candidates. Political Research Quarterly 64(2): 460–471.

Chooi, Clara. 2012. Sharizat Says Ready to Face NFC Allegations. Malaysian Insider. February 4.

http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/sharizat-says-ready-to-face-nfc-allegations/, accessed January 1, 2013.

Cinar, Kursat. 2016. A Comparative Analysis of Clientelism in Greece, Spain, and Turkey: The Rural–Urban Divide. Contemporary Politics 22(1): 77–94.

Dancz, Virginia. 1987. Women and Party Politics in Peninsular Malaysia. East Asian Social Science Monographs. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Derichs, Claudia. 2013. Reformasi and Repression: Wan Azizah Wan Ismail. In Dynasties and Female Political Leaders in Asia: Gender, Power and Pedigree, edited by Claudia Derichs and Mark R. Thompson, pp. 291–320. Zurich and Berlin: Lit Verlag.

Eradication of Poverty by MWFCD (Pembasmian Kemiskinan). https://ekasih.icu.gov.my/ekasih/Semakan/Pages/CarianProfailBantuan.aspx, accessed March 1, 2017.

Fortunato, David. 2017. The Electoral Implications of Coalition Policy Making. British Journal of Political Science. https://doi-org.libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/10.1017/S0007123416000430, accessed August 22, 2018.

Gomez, Edmund Terence. 2016. Resisting the Fall: The Single Dominant Party, Policies and Elections in Malaysia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 46(4): 570–590.

Halim Said. 2016. A Helping Hand for Single Mums. New Straits Times. March 13.

Htun, Mala. 2004. Is Gender Like Ethnicity? The Political Representation of Identity Groups. Perspectives on Politics 2(3): 439–458.

Institut Wanita Berdaya Selangor. https://www.facebook.com/Institut-Wanita-Berdaya-Selangor-123910564936763/, accessed October 17, 2017.

Jacoby, Wade. 2017. Grand Coalitions and Democratic Dysfunction: Two Warnings from Central Europe. Government and Opposition 52(2): 329–355.

Jamilah Ariffin. 1994. Reviewing Malaysian Women’s Status: Country Report in Preparation for the Fourth UN World Conference on Women. Kuala Lumpur: Population Studies Unit, University of Malaya.

―. 1992. Women and Development in Malaysia. Petaling Jaya: Pelanduk Publications.

Joshi, Devin K.; and Kingma, Kara. 2013. The Uneven Representation of Women in Asian Parliaments: Explaining Variations across the Region. African and Asian Studies 12: 352–372.

Karim, Wazir Jahan. 1993. Women in Politics in Malaysia. In Women in Politics: Australia, India, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, edited by Latika Padgaonkar, pp. 84–131. Bangkok: UNESCO Principal Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific.

Kartini Aboo Talib Khalid. 2014. Women and Politics: Social Construction and a Policy of Deconstruction. Journal of Social Sciences 10(3): 104–113.

Kaufman, Robert R. 1974. The Patron-Client Concept and Macro-Politics: Prospects and Problems. Comparative Studies in Society and History 16(3): 284–308.

Kokkonen, Andrej; and Wängnerud, Lena. 2016. Women’s Presence in Politics and Male Politicians Commitment to Gender Equality in Politics: Evidence from 290 Swedish Local Councils. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 38(2): 199–220.

Kopecky, Petr; and Spirova, Maria. 2011. “Jobs for the Boys”? Patterns of Party Patronage in Post-Communist Europe. West European Politics 34(5): 897–921.

Krook, Mona Lena. 2010. Studying Political Representation: A Comparative-Gendered Approach. Perspectives on Politics 8(1): 232–240.

Kumar, Kamles. 2017. MP Wants Government to Set Minimum Age Limit for Marriages. Malay Mail Online. April 3. http://www.themalaymailonline.com/print/malaysia/mp-wants-government-to-set-minimum-age-limit-for-marriages, accessed October 17, 2017.

Kwok, Yenni. 2016. Who Is the Woman at the Heart of Malaysia’s Anti-Corruption Protests? Time Magazine. November 23. http://time.com/4579854/malaysia-bersih-protests-leader-maria-chin-abdullah/, accessed October 17, 2017.

Lai Suat Yan. 2003. The Women’s Movement in Peninsular Malaysia, 1900–99: A Historical Analysis. In Social Movements in Malaysia: From Moral Communities to NGOs, edited by Meredith Weiss and Saliha Hassan, pp. 45–74. London: Routledge.

Lawson, Chappell; and Greene, Kenneth F. 2014. Making Clientelism Work: How Norms of Reciprocity Increase Voter Compliance. Comparative Politics 47(1) (October): 61–77.

Lee, Julian C. H. 2012. Shopping for a Real Candidate: Aunty Bedah and the Women’s Candidacy Initiative in the 2008 Malaysian General Elections. In Women and Politics in Asia: A Springboard for Democracy, edited by Andrea Fleschenberg and Claudia Derichs, pp. 19–39. Singapore: ISEAS.

Lemarchand, Rene; and Legg, Keith. 1972. Political Clientelism and Development: A Preliminary Analysis. Comparative Politics 4(2): 149–178.

Lim Guan Eng. A New Deal for Malaysians. Speech at the DAP National Conference, Shah Alam, December 4, 2016. https://dapmalaysia.org/statements/2016/12/04/24127/, accessed April 14, 2017.

Lim, Ida. 2013. No Votes Lost over Raja Ropiaah Issue, Wanita Umno Leaders Say. Malaysian Insider. January 6. http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/no-votes-lost-over-raja-ropiaah-issue-wanita-umno-leaders-say/, accessed January 7, 2013.

Loh, Francis; and Saravanamuttu, Johan, eds. 2003. New Politics in Malaysia. Singapore: ISEAS.

Mahfudzah binti Mustafa. 1999. Women’s Political Participation in Malaysia: The Non-Bumiputra’s Perspective. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 5(2): 9–46.

Malay Mail Online. 2015. DAP Supporters Overwhelmingly Male-Centric as Women Shy Away, Facebook Survey Shows. September 13. http://www.themalaymailonline.com/print/malaysia/dap-supporters-overwhelmingly-male-centric-as-women-shy-away-facebook-survey, accessed April 14, 2017.

―. 2014a. PAS Women’s Chief Denies Endorsing Dr Wan Azizah. September 2. http://www.themalaymailonline.com/print/malaysia/pas-womens-chief-denies-endorsing-dr-wan-azizah, accessed April 14, 2017.

―. 2014b. Political Parties Should Set 30pc Female Quota during Elections, Says Azizah. December 8.

http://www.themalaymailonline.com/print/malaysia/political-parties-should-set-30pc-female-quota-during-elections-says-azizah, accessed April 14, 2017.

―. 2014c. Dr Wan Azizah Lost Credibility When She Quit Opposition Leader Post, PAS Wing Says. September 8. http://www.themalaymailonline.com/print/malaysia/dr-wan-azizah-lost-credibility-when-she-quit-opposition-leader-post-pas-win, accessed April 14, 2017.

Malaysiakini. 2017. DPM: It’s Too Soon to Decide on Snap Polls for Sabah. February 11.

https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/372111#ixzz4YuRFu5xy, accessed April 1, 2017.

Malaysiakini Team. 2018. After Six Decades in Power, BN Falls to “Malaysian Tsunami.” May 10.

https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/423990, accessed August 22, 2018.

Malaysian Insight. 2017. Wanita Pakatan Pledges to Raise Women in Politics, Economy, Social Welfare. October 11. https://www.themalaysianinsight.com/s/18126/, accessed October 17, 2017.

Manderson, Leonore. 1980. Women, Politics and Change: The Kaum Ibu UMNO, Malaysia, 1945–1972. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Martinez, Patricia. 2003. Complex Configurations: The Women’s Agenda for Change and the Women’s Candidacy Initiative. In Social Movements in Malaysia: From Moral Communities to NGOs, edited by Meredith Weiss and Saliha Hassan, pp. 75–96. London: Routledge.

Maznah Mohamad. 2017. Increasing Women’s Representation in Malaysian Politics. Malaysiakini. June 9. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/385114, accessed October 17, 2017.

―. 2003. Women in the UMNO/PAS Labyrinth. In Risking Malaysia: Culture, Politics and Identity, edited by Maznah Mohamad and Wong Soak Koon, pp. 112–138. Bangi: Penerbit UKM.

―. 2002. At the Centre and Periphery: The Contribution of Women’s Movements to Democratization. In Democracy in Malaysia: Discourses and Practices, edited by Francis Loh Kok Wah and Khoo Boo Teik, pp. 216–240. Richmond: Curzon.

Molyneux, Maxine. 1998. Analysing Women’s Movements. In Feminist Visions of Development: Gender Analysis and Policy, edited by Cecile Jackson and Ruth Pearson, pp. 65–88. London and New York: Routledge.

Mulakala, Anthea. 2013. Where Are Malaysia’s Women Politicians? Asia Foundation. March 13.

http://asiafoundation.org/2013/03/13/where-are-malaysias-women-politicians/, accessed February 16, 2017.

Ng, Cecilia. 2012. Right Time, Right Place and with Some Luck: PWDC in the Making. Penang Monthly (April): 18–20.

―. 2010. The Hazy New Dawn: Democracy, Women and Politics in Malaysia. Gender, Technology and Development 14(3): 313–338.

Ng, Cecilia; and Lai, Karen. 2016. Debating Women’s Representation & Electoral Politics. Presentation at the national conference on Gender and Electoral Reform: Making a Difference, Penang, August 26–27.

Ng, Cecilia; Maznah Mohamad; and Tan Beng Hui. 2007. Feminism and the Women’s Movement in Malaysia: An Unsung (R)evolution. London: Routledge.

Noraini Abdullah. 1984. Gender Ideology and the Public Lives of Malay Women in Peninsular Malaysia. PhD dissertation, University of Washington.

O’Brien, Diana Z.; and Rickne, Johanna. 2016. Gender Quotas and Women’s Political Leadership. American Political Science Review 110(1): 112–126.

Otjes, Simon; and Rasmussen, Anne. 2017. The Collaboration between Interest Groups and Political Parties in Multi-party Democracies: Party System Dynamics and the Effect of Power and Ideology. Party Politics 23(2): 96–109.

Palansamy, Yiswaree. 2015. Hadi Tells Muslims to Be Angry with DAP over Hudud. Malay Mail Online. May 19. http://www.themalaymailonline.com/print/malaysia/hadi-tells-muslims-to-be-angry-with-dap-over-hudud, accessed April 14, 2017.

Pathmawathy, S. 2011. Sex Book Author Allows Peep into Bedroom. Malaysiakini. October 22. http://www.malaysiakini.com/news/179362, accessed October 22, 2011.

Perlez, Jane. 2006. Within Islam’s Embrace: A Voice for Malaysia’s Women. New York Times. February 16. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/19/world/asia/within-islams-embrace-a-voice-for-malaysias-women.html, accessed October 17, 2017.

Portal Rasmi Kementerian Pembangunan Wanita, Keluarga dan Masyarakat [Official portal of Ministry of Women, Family and Community Development]. http://www.kpwkm.gov.my/kpwkm/index.php?r=portal/about&id=Vzh2VVk4OURnWWtSNExlUkRGb2xpUT09, accessed March 1, 2017.