Contents>> Vol. 9, No. 1

Theatrical Governmentality and Memories in Champasak, Southern Laos

Odajima Rie*

* 小田島理絵, Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences, Waseda University, Toyama 1-24-1, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8644, Japan

e-mail: lectoda[at]aoni.waseda.jp

DOI: 10.20495/seas.9.1_99

In this article, I discuss cultural governmentality, its growth—as highlighted by multiple views in the past—and accretionary beliefs and religiosity that have emerged from the domestication of traditions in Southern Laos. In Champasak, visible ancient remains have long been indicators of the existence of guardian spirits, as well as religious beliefs, legends, and practices. The rites of worshipping the spirits have been demonstrated through staged ceremonial and ritual grandeur. This form of political art has been used to convey spiritual messages to the citizenry; however, such theatrical governmentality has not escaped the influence of scientific modernity. Thus, two phases of heritagization have occurred: French colonialization and the present periods of imposed scientific knowledge and politics that have created heritage sites and objects in the region. When modern knowledge dislocates spiritual worship and ambiguous memories of the past, the natives remember and craft legends and beliefs, or “unofficial” memories, in their pursuit of identity. By closely scrutinizing and recontextualizing these two encounters, this article elucidates how religious beliefs, legends, and memories redevelop as complex religious and political expressions of native selves.

Keywords: Laos (Lao PDR), Champasak, Wat Phu (Vat Phou), governmentality, religion, memory, archaeology, heritage

I Introduction

I-1 Wat Phu in the Past

Photos in the booklet by Henri Marchal (1959) show Champasak in the old days, with its emblematic site Wat Phu (Wat Phū; “Vat Phou” in French)1) (Fig. 1). Wat Phu is a well-known monument site in southern Laos. Presently, it is a tourist site; the large area surrounding it was inscribed on the World Heritage list in 2001.2) However, Wat Phu has drawn a great deal of attention for a very long time. Since the beginning of French colonization in the late nineteenth century, Wat Phu has attracted not only local residents but also explorers, scholars, politicians, and tourists.

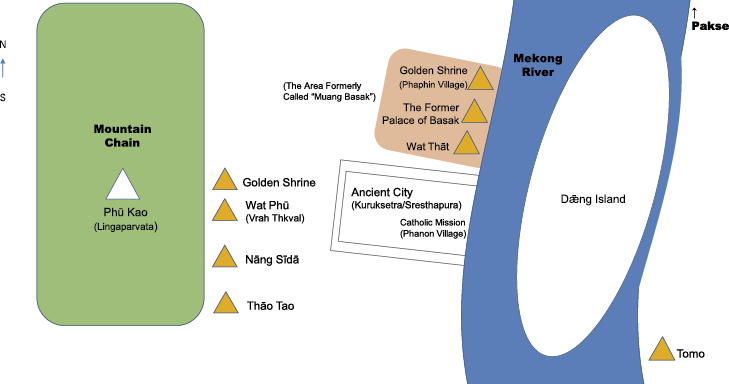

Fig. 1 Sketch Map of Champasak District (map created by author)

Three photos in the aforementioned booklet, which was originally published in French by Henri Marchal in 1957, were added when the text was translated into Lao by a dignitary and a member of the former Southern Lao royal court. They depict scenes of the Wat Phu Festival, one of the South’s most magnificent ceremonial festivities. Two of the three photos show that Savang Vatthana, Prince of Laos from the town of Luang Prabang, officially visited Wat Phu with his ministers in 1959, and that the ministers greeted Boun Oum (Bun Ūm), the late prince and last heir of the Southern Lao monarchy. The photos infuse the celebration taking place at Wat Phu with diplomatic tactics. Their insertion into the booklet reflects the translators’ intention to show that the Lao chiefs, particularly Boun Oum, were the governors of the Southern region. A semi-autobiography of Boun Oum (Archaimbault 1971) conveys the late prince’s feelings of grief, resignation, and powerlessness over the decline of the South in Northern-centered Laos. The translators, who were close to him, would have shared those feelings and added the three special photos as evidence of the closeness of the Southern monarchy to Champasak.

Modestly portrayed in both the French and Lao versions were the native Lao inhabitants who lived near Wat Phu and their feelings of friendship, respect, and awe toward the site. This closeness with Wat Phu still exists today, albeit in a less focused way.

I-2 Cultural Governmentality and Memories

In this article, my first aim is to elucidate the invention of certain political arts in Champasak, which employed fine arts on the political stage. I explore what Michel Foucault (1979) called “governmentality”—techniques, tactics, and discourses that embody forms of governing and polities under certain environmental and temporal conditions in the West—as a cultural product that emerged and was nurtured in Southern Laos, home to groups of ancient artifacts. I analyze the cultural uniqueness of Southern Lao governmentality based on documents written by French explorers, archaeologists, and ethnohistorians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly the ethnological documentation of Charles Archaimbault, who conducted extensive fieldwork in Champasak with a special focus on ceremonial and ritual features during the royal regime. I also use data collected and photos taken during my own on-site research in the early 2000s3) to examine how people lived with the archaeological sites and objects in Champasak, which had just become a World Heritage site. During this field research, I met elderly villagers who lived near archaeological objects or were involved in rituals conducted around the sites. I was not allowed to be alone in the village, however, due to the regulations of the current socialist government. When using these data, primarily in the later sections of the article, I take account of such particular present-day contexts.

These data sources illustrate what I call “theatrical governmentality.” The politico-societies of Tai groups have fitted themselves within different environments and realized culturally variable governmentality. Their religiosity takes a hybrid form, reflecting the ongoing lives and beliefs of living peoples, animating their own religious lives and sustaining the cultural governmentality of each group (Comaroff 1994; Hayashi 2003; Hayami 2004; Pattana 2005; Holt 2009; Endres and Lauser 2012; McDaniel 2014). This has given a unique shape to governmentality in Southern Laos.

These features are mirrored in the paramount tenet of political art in Champasak, or theatrical governmentality. In Champasak, as in other places in Southeast Asia where people live with ancient buildings and artifacts constantly in view, hybrid religiosity is sustained. Unique to Champasak, however, is that both native political actors and commoners reference beliefs that demonstrate “accretion” (McDaniel 2014) or “participation” (Lévi-Bruhl 1984 [1926]); these are conveyed by the ancient but still living artifacts, the messages of spiritual entities delivered through mediums, and various ritual spectacles and festivities invented or reinvented in the cultural public sphere.

To elucidate cultural governmentality and the religious specificity on which it is based, the materials present an image of French governmentality based in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century French modernity. The colonizers’ technological, scientific, mechanical, numerical, chronological, and typological knowledge, devices, and discourses on objects, time, and human and nonhuman entities were embodied in archaeological and political exploration and exploitation. Modern development of rationales relied on deduction, evolution, or diffusion rather than accretion or participation. The contrast between these tenets led their early contact to take the shape of an encounter. Thus, my second aim in this article is to closely scrutinize the development of otherness when the two sides—colonizing and colonized, one using modern science and the other using locally developed knowledge—encountered one another. This extends to an investigation of what Mary Pratt (1992) calls the “contact zone”: the temporal and spatial phase in which the others meet without the preexisting equilibrium of power. This can also be called a phase of “heritagization” (Smith and Akagawa 2009; De Cesari 2017) or a politicized phase of heritage, as, for example in Champasak, ancient objects become materials by which different groups contest their own views of the truth.

However, my analysis is not limited to the phase that developed during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; it also encompasses the present phase, which developed through the union of the sciences with local theatrical arts in response to the rise of the scientific World Heritage program. In both phases, scientific and ritual governmentality clashed over their perspectives of the past, objects, and religions. Ultimately, ritual governmentality and the aspect of the place as a home for villagers and their spirits were hidden behind scientific governmentality.

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, public crises and fears emerging from social struggles and dilemmas were often subsumed into religious phenomena, including millennialism. Such phenomena were either locally invented tactics to manage crises and insecurity or expressions (intentional or unintentional) of protest against the colonial or capitalistic other, and they were used against the modernity subsumed by that other (Worsley 1981 [1957]4); Ong 1987; Tanabe and Keyes 2002; Hayami 2004; Pattana 2005; Endres and Lauser 2012). Likewise, in Champasak, natives’ worship of spiritual entities expressed their feelings of insecurity regarding oncoming crises. Whereas orthodox religious teachings are reference points to embody governmentality and religious practices (Kanya 2017), the religious phenomena they re-realize do not equate to the old traditions; their beliefs and practices can be understood only as modern phenomena (Comaroff 1994; Hayami et al. 2003; Hayashi 2003; Hayami 2004; Holt 2009; Endres and Lauser 2012). This is particularly evident in the second phase of heritagization. In post-1975 Laos, where theatrical governmentality is unofficial despite its potency, a sharp demarcation is drawn between the past and the present, or between tradition and modernity, respectively (Rehbein 2007). As the industrious and realistic orientation and scientific education affect religious institutions and monks, the legitimacy of canonical Buddhism is apt to be overemphasized, and hybrid popular beliefs and practices may be denied (Ladwig 2012). In this strict atmosphere, understanding of heritage or religious monuments is standardized, and their spiritual potentiality is underestimated. Because of this trend, local beliefs in spiritual heroes in Champasak, which are closely tied to the existence of ancient monuments, have begun to reawaken and participate in living society as the local residents’ pursuit of identity.

Such local beliefs tend to be treated as historical anecdotes or memories shared within native circles only. However, if a memory is a continually reproduced representation of a living social group, as Maurice Halbwachs (1992) suggests, then so-called history can be regarded as a representation of scientific engagement. The “facts” are, therefore, multilayered, and we should take a multifaceted view when examining them.

When considering a multiplicity of facts, we must note how vulnerably, emotionally, and discursively the past and “truth” are produced in highly politicized and traumatic situations in the present. Halbwachs’s discussion of memory does not mention this (Rappaport 1998; Cole 2008; Shaw 2008). Multiple facts have been produced in phases of dispute in Champasak as an expression of various people’s struggles to define the past. Thus, by relocating the scientific position (and myself) as reflexively as possible, and by resituating histories/memories already unearthed in the excavation of the past, I aim to examine how different views have been produced and performed.

II Situating Champasak: Marginalization under French Rule

To begin the study, I first examine how Southern Lao experienced otherness and marginalization by the other. The marginalized position of the South was reinforced in two historical phases: first, the formation of French Laos by the unification of Lao principalities, the muang (mū’ang, ເມືອງ)5) of the three kingdoms (ānāchak, ອານາຈັກ) of Luang Prabang, Vientiane, and Champasak at the end of the nineteenth century; and second, the installment of the king of Luang Prabang as the monarch of the Kingdom of Laos (ānāchak lāo, ອານາຈັກລາວ) after decolonization. This occurred alongside the Siamese colonization of the three Lao kingdoms in the eighteenth century. However, these phases, especially French colonization, were dramatic for the Southern Lao population as they introduced a coercive encounter with the powers of modernity, technology, and science that remained until the end of the royal court. French colonization began to affect Southern Lao even before the territorial treaty was forged in October 18936) by way of explorers dispatched to investigate the geography and resources of the South, including ancient monuments. The treaty, signed by the Siamese and French administrations, effected a change in the Southern kingdom: Muang Basak7) (Fig. 1), the capital principality of the Champasak Kingdom located on the western bank of the Mekong, was excluded from eastern bank-centered French Laos. Although the western bank was included in French Laos in the second treaty, concluded in 1904, the French administration then established its headquarters on the eastern bank. The new central city of the South, Pakse (Fig. 1), was occupied by Vietnamese and Chinese settlers. Unlike the new settlers, who engaged in commercial, administrative, and other promoted activities, the residents of Basak were wet-rice cultivators, marginalized both economically and geographically. Under such circumstances, how could, and how did, the Lao population view, interpret, and remember the present and past?

II-1 Constructing a Memory: How the Prince Remembered the Past

It is evident in Archaimbault’s account The New Year Ceremony at Basăk (1971) that for Champasak, the past was a production of remembering and forgetting the specific historical and political moments in which it was situated. Archaimbault wrote his account through a lengthy communication with Boun Oum in the 1950s and 1960s.8) He included statements written by Boun Oum himself, who experienced the loss of his position as a prince within the Kingdom of Laos by ceding the throne to the Luang Prabang court in 1946.

The account vividly notes how Boun Oum remembered the past in this situation. Archaimbault, serving as a storyteller, begins with the prince’s discussion of his grandfather Kham Souk. Kham Souk established the royal court of Basak (Fig. 1) and encountered French expeditions in the late nineteenth century. Boun Oum told Archaimbault that his grandfather’s encounter with French explorers was the start of a nightmarish experience: Auguste Pavie, the main player in the French colonization of Laos, treated Kham Souk as nothing more than “a phantom king” (Archaimbault 1971, 18), being skeptical of his close ties to the Siamese. The account notes that Kham Souk died in anger and distress, degraded to chief of one district. The nightmare was then passed on to his son, Rāsadānai—Boun Oum’s father—who had to swear “allegiance to the French” (Archaimbault 1971, 18). After 1941, Basak once again became a point of territorial battle between France and Siam (Thailand). It became part of Siam and remained so until it was returned to Laos in 1946. The account records Champasak’s past through the filter of Boun Oum, who sketched out the deterioration of both the fame and pride of the Southern Lao monarchy. This distress did not belong specifically to Kham Souk or Rāsadānai, but to Boun Oum himself. Boun Oum felt toward Archaimbault what his father and grandfather had felt toward French colonization. Sensing this, Archaimbault states that Boun Oum’s narratives appeared like bǭk bān chai (ບອກ ບານ ໃຈ)—the rite of expulsion of sins, literally meaning “to tell (bǭk) is to open or to bloom (bān) a heart (chai),” in which sins are confessed as self-punishment. Archaimbault decided that the former prince lamented the decline of his grandfather, father, and country due to his incapacity. Boun Oum, however, stated that the Southern country’s decline was its fate: in Buddhist thought, karma was attached to the South, and caused by an “original sin” by an ancestor of the royal court in the remote past (Archaimbault 1971, 45–49). This ancestor was a sinful queen named Nāng Pao. Another of Archaimbault’s accounts, “L’histoire de Čămpasăk” (1961), regarded Nāng Pao as the key cause of the country’s misfortune. In “L’histoire,” however, the queen was a mythical figure with few concrete details: she was the only daughter and heir of a multiethnic kingdom consisting of Khmer, Indians, Cham, Lao, and Suei, called Năk’ônkalăčămpanak’ăbŭrisi. The kingdom was believed to have been situated around the villages of Katup, Muang Kang, Sang O, and Phanon before 1638 and to have had a good relationship with the Khmer monarchy (Archaimbault 1961, 523). The queen, whose ethnicity was unknown, passed her reign to the two Lao founders of the monarchy, the Buddhist monk Prakru Ponmesak and the prince Soi Sisamut, who came from Vientiane and established the order of the Southern region following Buddhism (Archaimbault 1961, 534–557).

Both Boun Oum and Archaimbault state in The New Year Ceremony at Basăk (1971, 14) and “L’histoire” (1961, 531) that the Southern kingdom fell into chaos during the reign of Nāng Pao because of the birth of her illegitimate daughter, Nāng Peng. Nāng Pao’s illegitimate pregnancy was considered to be the cause of all the bad luck that befell future generations. Boun Oum’s account raises a crucial theme in the governance of the Southern monarchy: gender and sexuality. He notes the importance of this theme in his own afterword in The New Year Ceremony at Basăk, in which he recalls how carefully his ancestors addressed gender and sexuality (Archaimbault 1971, 48).

Boun Oum’s narratives cannot prove the existence of Nāng Pao and other ancestral heroes. Historians can closely scrutinize his statements, but firsthand materials are rare, and if written materials or objects could be found, it would be difficult to determine their accuracy. It would be impossible to pursue such a positivist approach in its entirety because, although Archaimbault stated his written history was based on several sources—those authorized by Kham Souk, his dignitaries, a Lao monk, and Siamese dignitaries working for their royal court9)—the agency of the writers in shaping the facts remains uncertain. In the case of Boun Oum’s narratives, which are full of grief and sorrow, what is more certain is his view and way of interpreting the past and reconstructing a memory. We must consider what agency shaped Boun Oum’s own memory. As a man who experienced modernity and its marginalization of his country, Boun Oum was a postcolonial subject in a hybrid position between the colonizing and colonized cultures (Said 1993), and he could only feel powerless.10)

II-2 Muang and the People

During the period of the Southern country’s marginalization, the rite of purifying sins was important. Feelings of grief were not exclusively felt by the prince but shared by the people who participated in the rite. Furthermore, the prince’s reconstruction of the past was not solely an individual memory. Thus, ritualistic acts of purification served as important ceremonies. With respect to the New Year ceremony, Archaimbault notes that the sharing of symbolic acts established the harmonious relations of people with Muang Basak (Archaimbault 1971, 3–5).

Symbolic acts united the people, the royal house, and the authorities as an organic and lively community. Citizens who participated in the ceremony played the roles of both performer and observer. They were performers when they cleansed their bodies and purified the outer environment by accompanying the sacred procession with the prince as it circled the ritually central monasteries, and also when they sprinkled water on the prince and images of Buddha—the most powerful bodies symbolizing their principality and representing how and by whom the polity was managed and protected (Archaimbault 1971, 3–5). Subsequently, they completed the ceremony as observers. They observed that the rite was conducted promptly and smoothly, promising them safety and prosperity in the coming year (Archaimbault 1971, 3–5). This was the only way to officially end the ceremony, and the prince’s exhibition of the entire procedure to residents was thus a crucial task.

The significance of the people’s presence cannot be underestimated. The ceremony provided both the prince and the people with the opportunity to reconfirm their social and cosmological norms, as well as the political organization and protection, through enjoyment. Thus, the ceremonial settings of Southern Lao muang could be analogous to Clifford Geertz’s definition of the classical Balinese polity, the negara, as a “metaphysical theater state” (Geertz 1980), which was “designed to express a view of the ultimate nature of reality and, at the same time, to shape the existing conditions of life to be consonant with that reality” (Geertz 1980, 104). Southern Lao muang conducted the New Year ceremony at the turning point of the calendar, bringing governors and commoners together onto the stage of a grand “drama” in which they reconfirmed the ontological significance of their cosmos. As in the negara, in which governance operated via symbolic actions, in muang, politics was not a simple conduit of power but rather an art to help realize its grand function, inciting commoners to cooperate with the governing body and its associates.

III Theatrical Governmentality: How to Govern Muang

Although the features of Lao muang are analogous to the Balinese negara, muang were not exactly the same as negara. Each developed its own distinctiveness through unique cultural processes and the capacity to adapt to natural and social environments. We must thus more closely scrutinize each muang’s development of “theatricality,” or uniqueness in the art of conducting ceremonies for the political sake of each polity.

III-1 The Uniqueness of Lao Theater: The Cultural Public Sphere

The uniqueness of the Southern Lao art of governing muang can be seen most prominently in the popular way they relate themselves to the ceremonies and politics. We must first keep in mind that ceremonies are called bun (ບຸນ), a term with a double meaning: virtue or merit making, and participatory ceremonial occasions. Both meanings imply that individuals accumulate virtue or merit to achieve nirvana or eternal happiness (Nginn 1967), following the teachings of Theravada Buddhism. Thus, achievement of a state of happiness depends primarily upon individual practices, but individuals also engage in merit making and ceremonial occasions to gift their virtues to those around them. Thus, their virtues and happiness are to be shared by the collective. Lao ceremonial occasions, or theatricality, imply both individual and common good.

To scrutinize Archaimbault’s portrayal of the New Year ceremony, Bun Pī Mai (ບຸນປີໃໝ່), in terms of this theatricality, we can consider the ceremony to be an occasion for both individual and collective pursuit of happiness. The occasion was meaningless if not conducted in a space that was both open and accessible to individuals living together in the muang. Some rites were conducted within the palace, but the ultimate aim of such rites was to lead the muang and its people to happiness. Thus, the New Year ceremony and other ceremonial occasions were culturally designed to occur in the public sphere. The people were enthusiastic to join in this sphere because, being mostly agrarian farmers, they earnestly wished to secure a good rice harvest. This is illustrated by Archaimbault: “The prince goes downstairs and takes his seat under the veranda, where everyone . . . now sprinkles him in order to assure an abundant rainfall” (Archaimbault 1971, 13). This aspect—people participating in ceremonial occasions in hopes of gaining life security and religious happiness—may also be a distinctive feature of Southern Lao’s theatricality, running in contrast to the negara. Geertz portrayed the negara as composed of subjects who faithfully performed given hierarchical roles. Each actor was invariably obedient to the social and political scenario. Anthropologists skeptical of the image of individuals as anonymous members of culture or society may insist that Geertz, in accordance with his early theories, customarily interpreted people as socially embedded objects, and thus he depicted the negara as a hierarchical, well-organized theater. Such critiques alert us that facts are filtered through writers’ eyes.

All we can draw with certainty from Archaimbault’s portrait of the New Year ceremony is that diagnostically, the muang’s residents were highly sensitive to socially expected roles and codes, which were conveyed through ceremonies. However, they were not merely recipients of these codes but creative performers who interwove their own will into the drama. Archaimbault’s portrayal suggests that if the theatrical public space did not allow individuals to live on their initiative, the theater would have been empty. In this respect, the Southern Lao public sphere was unlike the Balinese theatrical sphere.

In Southern Lao muang, ceremonies were important arts that connected the people to their lords. Indigenous politics were successful if they could stimulate people’s enthusiasm for living. An interview with villagers who participated in ceremonies during the old regime revealed that the festivities conveyed religious excitement and feelings of pleasure for their lives. The most impressive ceremonial event was bun sūang hū’a (ບຸນຊ່ວງເຮືອ), the boat racing ceremony. It was exciting because it had multiple meanings: human, ethnic, economic, and political. Such scenes can be observed again in Archaimbault’s research (1972). Racers came from all the lower regions of both banks of the Mekong, the farthest coming from the border area of present-day Cambodia, to the main stage in Muang Basak. In the area of the palace was a miniature Mount Meru (according to local belief, a physical representation of the peak of the world), located in the center of the Southern kingdom. The spatial range of the capital city Basak was marked and protected by two important shrines: the Golden Shrine (hǭ kham, ຫໍຄຳ) in Phaphin Village, which enshrined the great guardian spirit of the capital of the kingdom (phī mū’ang, ຜີເມືອງ), Chao Thǣn Kham (ເຈົ້າແຖນຄຳ); and Wat Thāt (ວັດທາດ), the monastery that enshrined the royal Lao founder and guardian of the capital, Soi Sisamut (Fig. 1).

The people who performed the boat racing ceremony expressed appreciation and homage toward the divine dragon, Nāga, which controlled rainfall and was thus the farmers’ subsequent lifeline. At the same time, the ceremony provided a multitude of entertainment, offering people the opportunity to dance and sing with others from different villages and districts. Finally, the ceremony afforded the opportunity to purchase rare products brought by traders from all over the lower Mekong region (Archaimbault 1972, 62).11)

By hosting the ceremonies and integrating the rituals with trading and entertainment, the former Lao monarchy could control the public. By gathering racers and dignitaries from villages and small muang in the lower Mekong region, they also could recognize those in their mandala (Stuart-Fox 1997, 7) or galactic world (Tambiah 1976, 109). The ceremonies demarcated the border of the universe, not by drawing a borderline of the kingdom but by inspiring the imagination and performance of the ceremony’s participants.

III-2 What Is Shown in Lao Theater? Controlling Sexuality and Regulating Society

If ceremonies were indigenous arts for governing muang, we should carefully examine what participants were shown. As noted previously, in Champasak Boun Oum considered it important to regulate female sexuality. The theme of the sinful queen was staged repeatedly in important ceremonies and rites, including the sacrifice of buffaloes.12) This sacrifice was carried out at the Golden Shrine, which was built in the precinct of Wat Phu (Fig. 1). Based on his participant observation in the 1950s, Archaimbault (1959) described the procedures of the rite, unlike early explorers, who concerned themselves only with the architectural and archaeological features of Wat Phu. His research suggests how Nāng Pao’s original sin was related to regulating female sexuality by highlighting the villagers’ belief that Nāng Pao had cursed them:

If any young girl follows my example and lets some young lad make love to her to the extent of becoming a mother, then let her offer up a buffalo to the guardian spirits. . . . If not, then may the rice in the rays perish when the ears are forming, may the rice in the rice-fields dry up and die! (Archaimbault 1959, 160)

According to Archaimbault, following this curse, villagers searched for unmarried mothers in the greater area around Wat Phu and asked those women to offer buffaloes to the guardian spirits worshipped during the rite. He suggests that the main reason Lao communities sacrificed buffaloes was their adherence to local Lao oral tradition, which said that the founder of Wat Phu, Kammathā (ກຳມະທາ), offered human sacrifices to the guardian spirits (Archaimbault 1959, 156). At some point in the past, the rite transformed into a sacrifice of buffaloes because “the blood of a buffalo is of equal value with the blood of a man” (Archaimbault 1959, 156). Archaimbault does not indicate why Nāng Pao was drawn into the scenario; however, he obviously believed that the Lao attached their legend of Nāng Pao to a pre-existing rite of sacrifice. He followed the hypothesis of his fellow scholar George Cœdès, who translated the late-fifth-century Sanskrit inscription K365 discovered in Champasak (the details of this inscription will be discussed later). Cœdès suggested that in the remote past, a rite of human sacrifice was practiced by a king with a name other than Kammathā. Archaimbault, accordingly, believed the original rite to have begun in the remote past with someone other than Kammathā (Archaimbault 1961, 519–523). In Archaimbault’s perspective, the Lao attached their legend of Kammathā to the scenario of the sacrifice. Likewise, Archaimbault thought that the Lao legend of Nāng Pao was incorporated into the previously existing rite of sacrifice.

Archaimbault’s proposition suggests that, by reinterpreting and incorporating pre-existing religious practices into their own traditions, Southern Lao people reproduced their theatrical governmentality. This domestication of various beliefs and practices for their own use, with special attention to female sexuality, is also suggested by the Southern Lao recreation of other myths. First is the genesis myth of the Southern world, which stated that their world began with an accident caused by a female divinity who had an illegitimate child with her servant (Archaimbault 1964, 61–63); second is the oral tradition of a Lao woman named Nāng Malong, telling of her illegitimate love with a young non-Lao prince and ending in her suicide (Archaimbault 1961, 525–526). The main themes of such myths were female sexuality and misfortune, including interethnic marriage, caused by women’s misconduct. As Archaimbault mentioned (1961, 525–531), however, those stories share a resemblance to myths of Northern Lao principalities. Although female sexuality was a common theme in the region, the myths were not simply disseminated to the South; the Southern Lao found it necessary to transform them into theatrical governmentality.

Why was female sexuality an important theme? There is no critical answer. However, considering that important messages were transmitted during ceremonial performances, and that voluntary participation in ceremonial/political occasions was respected, it is possible that female sexuality was a difficult problem for the “liberal” government to solve.

It is unclear why interethnic marriage was narrated and performed as misconduct in myths and ceremonial occasions. Most likely, it was to maintain a hierarchical relationship between Lao and minorities,13) as in the case of royal ceremonies held in Luang Prabang (Lukas 2012). In Champasak non-Lao minorities played a significant role in ceremonies, but the Lao imposed a hierarchical relationship between the minorities and themselves. This relationship is well illustrated in the procedure of the boat racing ceremony (Archaimbault 1972). Some minorities, who were considered “original inhabitants” and thus legitimate conductors of rituals to call upon ancestral spirits, came to this ceremony to initiate the sacrifice of the buffalo to the guardian spirits. Others struck gongs, danced, and sang to call up the tutelary spirits of the land. One such song included both Lao and non-Lao lyrics, preaching the miserable end of interethnic marriage. By including non-Lao people in ceremonies, the Lao monarchy could ostensibly exhibit the Lao people’s superiority. Thus, minorities took part in the Lao theatrical governmentality not as the principal actors, but in supporting roles.

IV The Making of History: Gazing upon Antiquity

In Lao theatrical governmentality, festive occasions, myths, and legends were vehicles to convey symbolic messages to the people, particularly those concerning moral codes connected to female sexuality. In this governmentality, myths and legends were not fantasy but socially authorized historiography, or “correct history.” This “history” was, however, vastly different from the “history” created by French explorers and scholars in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. French history was produced by scientific specialism, objectivity, and the measurability and traceability of materials. In contrast, Lao traditional governments’ history was crafted by providing people with opportunities for performance and celebration as social welfare.

IV-1 The French Version of History and Its Methodology

French scholars created a chronological history and gave the names of non-Lao founders and monarchs to the old artifacts and buildings scattered around Champasak. They developed this history in the form of texts to understand the past, writing about the causes and effects of events, piecing together fragments of evidence. This practice was initiated by nineteenth-century explorers. In the early twentieth century, the “amateur” work of French scholars was integrated into the work of a scholarly organization known as the French Archaeological Mission, which ultimately became L’École Française d’Extrême-Orient (French School of the Far East).

Considering that the early explorers “discovered” and documented a dense distribution of ancient objects around Basak (Aymonier 1901; Lunet de Lajonquière 1907; Garnier 1996; Harmand 2010), the dwelling area of the Southern Lao monarchy became of interest to the organization. These ancient remains, particularly Wat Phu and other standing stone buildings, suited the French administration’s hopes of finding evidence of past and present affluence, as well as testing their knowledge. Particular political attention was paid to Wat Phu because it resembled Angkorian architecture, exhibited as a symbol of French Indochina in museums and expositions.

Epigraphists and conservators of the French School, such as Auguste Barth (1902), Louis Finot (1902), and Henri Parmentier (1914), published studies of the archaeological features and translations of the Sanskrit and Khmer inscriptions based on rubbings. Champasak was, however, too remote for extensive investigations on-site. The scholars’ offices were located in major cities within Indochina, and the greatest concern of the French School, following administrative policy, was the restoration of gigantic buildings. Given these restrictions, surveys in Champasak were limited, and the regional culture—particularly Lao culture in Southern Laos—was of far less interest until Archaimbault began his fieldwork in the 1950s.

Investigation and collection of ancient objects was allocated to French administrators or treasury researchers stationed in the French office. Those engaged in the Mission Conservatrice (Conservation Mission) were most interested in the statues with old Sanskrit and Khmer engravings.14) The inscriptions were prized as evidence the researchers could use for absolute dating. If the inscribed statues and other artifacts were small enough to carry, they were sent to museums established by the French administration in Indochina, or to museums in France.15)

The most active agents of the Conservation Mission, however, were members of the French Catholic Mission (hereafter “French mission”)16) who settled in Champasak in the late nineteenth century. With the aim to “[e]vangelize the people of Laos” (Tournier 1900, 130), the mission established a settlement and built a cathedral in the area around Phanon Village, located within several kilometers of both Wat Phu and Basak (Fig. 1).

When the mission arrived in Phanon, the area appears to have been sparsely populated. The early explorer Étienne Lunet de Lajonquière said, on his visit to Champasak in 1905, that locals preferred not to dwell in the Phanon area, which was scattered with bricks from collapsed structures, because they believed it was once a city created by the Cham and that the area was haunted by their spiritual entities (phī) (Lunet de Lajonquière 1907, 76). It is difficult to confirm the truth of the existence of the Cham spirits in the oral tradition. Considering that the area was the arrival point of the heroic Lao ancestors Prakru Ponmesak and Soi Sisamut, it is unclear whether the Lao would have abandoned it. Considering that the present villagers frequently moved settlements due to maladies caused by the spirits, it is unsurprising that the Lao refrained from living around a spiritual area. Despite this ambiguity, according to Lunet de Lajonquière’s information, the French mission chose to settle in the area because the Lao did not reside in it for fear of the spirits.

This decision led the French mission to form close connections with the ancient remains. Phanon Village was located in the area of Champasak most thickly scattered with archaeological remains, meaning that members of the mission could begin to conserve ancient artifacts immediately. One such object was a two-meter statue discovered along the bank of Hūai Sa Hūa (Sa Hua River), a branch of the Mekong. After the statue was discovered, the mission placed it in Phanon. It is uncertain why they did not transfer the statue to a French museum. Considering the difficulty of carrying a huge stone object all the way to a central city, it could be that preserving it on-site was merely a method of conservation, or that the mission may have been afraid of damaging the statue. In any case, the mission kept the statue for decades after its discovery (Lunet de Lajonquière 1907, 88–89; Cœdès 1953, 9; 1956, 210).

The stone statue was shaped like a lingam, a symbol of Shiva, and had Sanskrit inscriptions on its four surfaces. It became the focus of French investigation. Around the early 1930s, a French administrator took a rubbing of the inscriptions at Vat Luang Kao village, which neighbored Phanon. The rubbing was of poor quality, however (Cœdès 1953, 9), and the geographic remoteness prevented epigraphists from reading the inscriptions. It was not until the early 1950s that Cœdès (1953; 1956) studied and fully translated the statue’s inscriptions.17)

The inscription was numbered K365 in the French inventory. Some began to call it the inscription of Devānīka (Mahārājādhirāja Çrīmāñ Chrī Devānīka), after the king named in the inscription. K365 became renowned as significant evidence of “pre-Angkorian” history; Cœdès incorporated Angkorian inscriptions, Khmer oral tradition, Chinese texts, and K365 in his examination and created a grand history of the region. To French scholars who were concerned about how and why the Khmer formed the Angkorian Empire, and who were interested in the history of the lower Mekong region, his hypothesis was very insightful.18)

Cœdès portrayed Champasak, where the Lao were already the dominant residents at the time of his study, as the historical stage, related to Cham, Chenla, and Khmer. Studies of K365 and other inscriptions from Champasak also showed that Wat Phu was called Vrah Thkval (Aymonier 1901, 163–164; Lunet de Lajonquière 1907, 75) and the venerated god was Bhadresvara (Cœdès 1956, 213; 1968, 66). None of these names, however, appear in Archaimbault’s studies of Southern Lao traditions. Paradoxically, Cœdès left some keywords appearing in K365 unexamined, including the rite of sacrifice, Kuruksetra (the name of the place, according to Cœdès [1956]), and tīrtha (a domain of sacredness, according to Diana Eck [1981; 2012]), although those are important for understanding the ancient governmentality of Champasak.

K365 stated that Devānīka, a great conqueror, came to and invented “tīrtha,” named “Kuruksetra,” and conducted the “rite of sacrifice” toward “fire.” Given that Devānīka led the sacrifice as a rite of purification, he acquired merit, conferred it on Kuruksetra (as created by Devānīka), and prayed that both the dead and the living would share it (Cœdès 1956, 217–219). Cœdès (1968, 75) concluded that Devānīka sacrificed humans to powerful spirits, following the texts of the Sui Dynasty as they relate to Chenla.19) To be precise, no critical statements in K365 state that the sacrifice was of humans; however, this hypothesis was accepted as an absolute truth. As noted in the previous section, by accepting Cœdès’s interpretation as an absolute fact, Archaimbault regarded human sacrifice as the origin of the buffalo sacrifice, despite the lack of any supporting evidence aside from the Chinese document.

Cœdès’s interpretation had an influence on many scholarly discussions; however, it had its limitations. For instance, epigraphic studies (Cœdès 1956, 212; Jacques 1962, 250) did include the important keywords “Kuruksetra” and “tīrtha,” but they were scrutinized only modestly. These studies noted that K365 reflected the lyrics and cosmology of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and thus suggested that ancient Champasak was a theatrical country, like the existing Indian city of Kurukshetra.20) Thus, they treated the cosmological lyrics and the name of Kurukshetra inscribed in K365 as evidence of “Indianization.” However, because they failed to closely scrutinize the meaning of tīrtha, they interpreted Indianization superficially. According to Eck (1981; 2012), a tīrtha classically indicated a sacred spot or place, such as a crossing, river, temple, or mountain. A tīrtha was not sacred in its own right; the sacredness of tīrtha, like Kurukshetra, was dependent on sacred acts, including purification, performed by visiting pilgrims. The sacredness of tīrtha and Kurukshetra were never guaranteed without the practices of living people.

Epigraphists were not indifferent to the two keywords of “Kurukshetra” and “tīrtha.” Nevertheless, because they could not witness the fragile and ambiguous actions of pilgrims, which were rarely reflected in written testimonies, they concluded only that the ancient governmentality described in the inscriptions was evidence of the static phenomenon of Indianization. Indianization could be a complicated and ambiguous process, however, just as a tīrtha could be a dynamic realm.

French investigations sought to acquire evidence using new technology, but there were limits to its interpretation. With the advent of aerial photography in the mid-twentieth century, Archaimbault and the French Service of Information provided Cœdès with a bird’s-eye view of the area. The epigraphist then found double-folded walls situated over a large area around Phanon Village (Fig. 1), including a number of archaeological remains (Cœdès 1956, 220). He concluded that they were the walls of Kuruksetra (Cœdès 1956, 220). After the appearance of the aerial photo, however, the ancient city began to be called Sresthapura, a legendary Khmer city, instead of Kuruksetra, although no archaeological materials supporting the existence of Sresthapura in Champasak were discovered. This was in large part due to scientific concerns tied up with Angkor-centered history. In accordance with Khmer legends that the earliest Angkorian Empire was born with the early Khmer King Sresthavarman, around an area geographically similar to Champasak, the walled city became known as the Sresthavarman’s city of Sresthapura (Archaimbault 1961, 519).21)

IV-2 The Local Lao Version of History and Its Methodology

Lao history contrasts with the French history of Champasak with respect to appreciation of ancient objects. Considering the documents written in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Lao inhabitants can be assumed to have viewed all the great remains as sacred devices that contained the special powers of the spirits, which controlled the fate of the principality and the people. Caring for such objects was the duty of the Lao royal court, the holder of the ancient objects. Ancient artifacts were not displayed in museums but exhibited as active objects on the stages of ceremonies, or as symbols of welfare and protection for the living people. The site of Wat Phu was considered the oldest Mount Meru, the center of the universe, or the oldest palace (phāsāt, ຜາສາດ), which was guarded by spiritual powers. According to Lao inhabitants Archaimbault (1959; 1961) met in the 1950s and 1960s, one of the spirits with the greatest power was not Cham, Chenla, or Khmer, but rather King Kammathā, known in their oral tradition as the founder of Wat Phu. The villagers honored the spirit of King Kammathā by sacrificing buffaloes. However, as noted previously, in the oral tradition of Lao villagers, Kammathā conducted human sacrifices at Wat Phu in the remote past. The Lao villagers thus took over the rite from Kammathā. By holding the rite, regardless of their use of buffaloes, the Lao people declared to the spirit that they governed their country.

Kammathā rarely appears in the mainstream French version of Champasak’s history because no inscriptions or other written materials support his existence. Unlike other explorers, Etienne Aymonier (1901, 164–165), who traveled to Champasak in the late nineteenth century, noted that in the local Lao oral tradition, Kammathā was the founder of Wat Phu. However, Aymonier wrote that Kammathā was a legendary figure, stating that the oral traditions differed from written materials that could be used as evidence in scientific studies.22)

Archaimbault (1961), too, treated Kammathā as a legendary king. The sole instance in which Kammathā is mentioned is the chronicle written by Kham Souk and his dignitaries at the request of the Siamese in the late nineteenth century (Archaimbault 1961, 579). This chronicle was not intended to be printed and disseminated to the public. Rather, its contents were meant to be transmitted to the public in the cultural and ceremonial public sphere as real history, or in a way that attracted little scientific attention.

Despite positivists’ skepticism over King Kammathā’s existence, Lao communities shared the story about him in the form of ritual performance and narrative. In culturally authorized time and space, local residents believed it was not Devānīka, the Cham, the Chenla, or the Khmer kings, but Kammathā himself who was the heroic founder and initiator of the area’s history. In the oral tradition, Kammathā had a daughter named Nāng Sīdā, the main figure in the oral tradition titled “Mr. Katthanam.” This oral tradition concerns a heroic and mysterious prince who was married to Nāng Sīdā (Aymonier 1901, 164–165). In the story, Nāng Sīdā is represented as a model woman embodying intelligence and beauty (Archaimbault 1961, 521–523).23) Although she was also treated as a mythical figure by explorers and scholars, she too was a real princess to native Lao communities. As the stories of Queen Nāng Pao and other sinful women carried codes of sexuality and marriage in the monarchical regime, the stories of Kammathā and Nāng Sīdā also served to convey to the people their true history.

Lord Kammathā, Princess Sīdā, and all other “legendary” ancestors were considered not dead but “living” when their legends were remembered and narrated by Lao communities. As will be discussed later, these ancestors remain living in the present as they are worshipped in ordinary or ceremonial times and spaces. They are not only commemorated but also incarnated through the bodies or voices of ritual masters or mediums. Thus, Lao society illustrates what Lucien Lévi-Bruhl called “participation”: the “opposition between the one and the many, the same and another does not impose this mentality, the necessity of affirming one of the terms if the other be denied, or vice versa” (Lévi-Bruhl 1984 [1926], 77). In Lao society, old artifacts and legendary people were in a sense both dead and living, coexisting with the living villagers in their society.

During my fieldwork in the early 2000s, this feature was evident in my communication with and observation of the living inhabitants and the master of rituals. Those who lived in the village situated closest to Wat Phu and the other ancient places said that the spirits of the “legends” remained in the region. In Lao governmentality, the existence of the ancestors and spirits was anchored to performativity, subjectivity, and the remembering and forgetting of members of society, as was the past. History was interwoven in the course of inclusion, exclusion, and domestication of traditions. This historicization, however, was marginalized when it encountered science. Due to the exclusion of the ritual authorization of history, a phase of dispute developed between the two versions of history.

V The Encounter of the Spirits with Modern Science

The moment at which scientific and modern governmentality encountered theatrical governmentality was documented in the travelogue of the French explorer Lunet de Lajonquière (1907). As mentioned previously, Lunet de Lajonquière noted that although the Lao inhabitants were frightened by the spirits and preferred not to live around the Phanon area, the Catholic Mission chose to use the area as a base (Lunet de Lajonquière 1907, 76).24)

This was the first meeting between science and the spirits, old artifacts, and Lao governmentality. If the Lao felt fearful toward spirits, as the travelogue noted, we may presume that, out of awe and respect, the locals could hardly touch the ancient remains and would have therefore “conserved” the objects in situ. If a person were to carelessly touch one, the spirits might impose adverse repercussions. During my fieldwork I often heard Lao inhabitants express such fear of the spirits. Some said that villagers used to move their settlements when maladies were imposed on them by the spirits. In many cases, the villagers said the same thing regarding spiritual spots scattered with ruins.

More stories from inhabitants supported the hypothesis that not only the various French missions but also natives and the royal house engaged in the conservation of ancient artifacts. One story concerned the inscription of K365. The French catalog noted that the Catholic Mission handled K365 either in their village, Phanon, or in the neighboring village of Vat Luang Kao. However, at some point during the twentieth century, the statue was transferred to the palace at Basak. The royal house kept the statue for decades until it was transported to the exhibition room of the museum, which was built in 2002 after the large area obtained World Heritage site designation.

The royal house placed K365 at the entrance, as if it were a symbol of the house. From the perspective of theatrical governmentality, this “exhibition” would represent the art of governing the Lao polity: showing a symbolic object signaled that the palace was the center of the principality. Although it was not possible to ask the house why K365 was “conserved” outside, many native narratives suggested that the house employed the traditional art of managing the polity by governing ancient objects. Those narratives said that in the old days, when people found artifacts near their living environments, they delivered them to the palace, which was considered the most appropriate place to manage extraordinary objects. The Lao palace therefore served as a “storehouse” or “museum,” as Grant Evans (1998, 122) noted.

Ironically, these stored artifacts did not have corresponding information about the dates and states of discovery, so when museological and curatorial knowledge arrived with the World Heritage designation, the traditional methods of conservation were criticized as “incorrect.” Under Laos’s socialist regime, which pursued modernization, theatrical governmentality was considered to be so old and contradictory that it obfuscated the facts.

V-1 The Second Phase: The Old Man Who Lived in the Ancient City

Around the 2001 inscription of Champasak on the list of World Heritage sites, historical investigation, interpretation, conservation, and restoration began to revisit Champasak. Based on my fieldwork, I discuss how and why facts multiplied, reexamining the participation of the dead in the living society, and the involvement of the physical in that belief.

A conversation with an elderly villager living within the walls of the ancient city of Kuruksetra/Sresthapura illustrates how the pursuit of truth may make our realities converge. I visited the resident’s village in 2002, when I was still unknown to the villagers. I was accompanied by two local officers, an older man and a woman interpreter, who were dispatched by the local authorities to oversee the research. My meeting with the elderly villager was an opportunity to learn how vulnerable the past was. To determine general information about the village, I asked several questions, including some about his personal life and the history of the village. In response to my questions about the history of the village, the old man began talking about the “Conservation Mission” of the native population. He said that the royal court and the villagers had come together to create the village, which was located in the heart of Kuruksetra/Sresthapura. According to the man, his village had been created when the palace ordered the citizens to establish a village in an area densely covered by fragments of ancient bricks, with the intention of having the residents manage the remains. The man, who stated his age at about 70 years, reported that this order was given about “100 years ago,” equivalent to “two or three generations before.” The interpreter asked him for a precise year, but he did not provide one. He spoke with her quickly and in unidentifiable words but did not offer me any more details. The old man and my associates seemed to talk amongst themselves and did not continue the investigation.

I discovered many years later that the old man’s information was somewhat confusing when referring to a description of the same situation by a French explorer. A French travelogue I read in 2010 (Lunet de Lajonquière 1907, 76) mentioned that Lao inhabitants refrained from establishing settlements around the ancient city because they were afraid of the curse of the spirits and the ancient remains. Nonetheless, a sketch map (Lunet de Lajonquière 1907, 78–79) showed the village that I visited, with exactly the same name and location. If the village truly existed in 1905, then who issued the order to create it, and when? The monarchical history reveals that Kham Souk died in 1900, and Rāsadānai took over in 1903.25)

By 2010 I had had a few opportunities to meet with another old man from the village who took care of the spirits. He said that the spirits dwelled around the ancient remains. He also spoke about foreign researchers he had met at the ancient remains in the 1990s. He thought that the researchers had come to his village to dig for gold, because when he was sleeping the spirits conveyed to him that gold was present. Although he did not criticize the researchers, he had been unwilling to see them.

When I found the French map in 2010, I recalled both stories and considered that the visits by outsiders would have been shocking to the villagers. In particular, during the period of French colonization in which ancient materials were of great interest, it made sense that the Lao royal court—Kham Souk, Rāsadānai, or others—would have created a mission to protect the objects and spirits from colonization, regardless of citizens’ fears of spiritual curses. To lose the ancient remains would have meant losing a way to communicate with their spiritual guardians; the Lao royal court’s resistance would have been reasonable.

The stories raised questions that my positivistic investigation could not definitively answer. As a researcher from a foreign country, I found it difficult to obtain supporting data that provided details with a signature from the author(s). I was unsure how to acquire data that supported the narratives. Even if I had another opportunity to meet these old men, it would be difficult to move from the fragile past to a fieldwork context, when stories of the old regime would still trigger political confusion. Eventually, I realized that there might be unspoken stories. The silenced, untouched element in the old men’s speech was obviously the archaeological history of Champasak. The officers who accompanied me engaged in the present art of governing foreign affairs and instructed me to be on their side. They appeared to imply that they controlled the research. Thus, the two old men appeared to claim ownership of the ancient sites, over both the officers and me.

If I had been more in tune with the context in which the old men were situated, I could have asked more insightful questions and had better conversations with them. The same thought occurred to me in 2015, when I had the opportunity to meet with Lao authorities. They had visited the old men’s village in the 1990s to acquire new archaeological materials to add Champasak to the World Heritage list. When I spoke with these authorities, they implied that they felt the villagers were unwelcoming. They said that not many villagers had seen an archaeological excavation, and most did not know what was going on. I recalled the old men’s stories upon hearing this, and realized that their mission to protect the ancient remains might have been reactivated when the authorities visited the village. When I visited, the villagers would also have watched me carefully. When outsiders began to visit Champasak to see the ancient objects, the old men and other villagers may have resumed their mission to protect both the antiquities and the village.

It is difficult to find the absolute truth about these situations. Different people are concerned about Champasak’s past and present. Not all would necessarily respond to a positivist inquiry of the past. Thus, all I could ascertain was that the facts were delicately constructed.

V-2 The Second Phase: The Masters of Ritual Who Lived in the Precinct of Wat Phu

In 2008 I had the opportunity to talk with the masters of the ritual who lived at the neighboring site of Wat Phu. At that time, the sacrifice of buffaloes had been modified to a sacrifice of chickens in accordance with the “saving-first” policy of the socialist government. The ceremonial governmentality tended to be overlooked by society as a whole.

The village of the masters, located next to Wat Phu, was known as a home to people who had been in touch with the guardian spirits. Male mediums, such as Mǭ Thīam (ໝໍທຽມ), who could be possessed by spirits, and Mǭ Cham (ໝໍຈັ້ມ), who could talk with spirits, were the main conductors of the rituals; female mediums, Mǣ Lam (ແມ່ລຳ), who communicated with spirits by dancing and were concerned with curing diseases, lived with other villagers. These masters played the main role in communicating with the ancient founder of Wat Phu and other spirits authorized as guardian spirits of the principality in oral traditions and myths, along with other masters of the Golden Shrine in Muang Champasak (formerly Muang Basak) (Fig. 1).

Mǭ Thīam, who was over 70 years old, said that the spiritual entities had continued to monitor Champasak, with each establishing its own base. Thǣn Kham (ແຖນຄຳ), Nǭi (ນ້ອຍ), and Thamphalangsī (ທຳພະລັງສີ) were at the Golden Shrine next to Wat Phu, where the masters conducted the sacrifice. Each mountain lying beside Wat Phu was a base for the great spirits of Surinyaphāvong (ສຸຣິຍະພາວົງ), Lāsaphangkhī (ລາຊະພັງຄີ), Phāsathū’an (ພາສະເທືອນ), Ongkhot (ອົງຄົດ), Champāvongkot (ຈຳປາວົງກົດ), Thǭnglǭ (ທອງຫລໍ່), and Mǭkasat ( ໝໍ່ <ໝໍ> ກະສັດ). The ancient buildings were occupied by the spirits of Nāng Ekhai,26) located in the stone-built monument, called Tomo, on the eastern bank, and Kammathā, located in Wat Phu (Fig. 1).27)

Mǭ Thīam did not mention the spirit of Nāng Sīdā dwelling at the ancient stone building complex named for her, which was located within a kilometer of Wat Phu (Fig. 1). Even so, just as her story was a favorite of present Lao communities, many inhabitants continued to commemorate her, although in a different place. As Aymonier noted, the location bearing her name was originally one of two galleries standing in the lower terrace of Wat Phu, not the smaller-scale stone building in the complex a kilometer distant (Aymonier 1901, 164–165). Her name was most likely removed from the gallery of Wat Phu because the scientific investigation at Wat Phu began in earnest during the French colonial period, during which the gallery became known by a different name. After Nāng Sīdā’s “expulsion” from Wat Phu, however, the monument complex nearby became known as the “building of Nāng Sīdā” (hōng Nāng Sīdā, ໂຮງນາງສີດາ) in native circles. People do not remember when the removal occurred, or if there even was one; however, both the site and the building named for the ancient princess remain, reflecting local remembrance of her.

The vulnerability of the past to the present situation continued to fill me with confusion. To combat this, I did not talk about my research before my conversation with Mǭ Thīam. After describing the guardian spirits, the master of the ritual described the procedure for sacrificing the buffaloes. He told me that the sacrifice was conducted in a way very similar to the procedure noted by Archaimbault. Historically, unmarried mothers had to sacrifice a big black buffalo to the great spirits at Wat Phu as compensation for their guilt. Mǭ Thīam said nothing about the curse of Nāng Pao and its relation to the buffalo sacrifice. When I asked, he said he had not heard the name of the ancient Queen Nāng Pao or about her curse.

The master of the ritual told me what he had seen and experienced during the sacrifice of buffaloes in the past. Then, there were a number of unmarried mothers around the region, so the masters conducted the sacrifice with buffaloes every year. During the sacrifice, the masters and participants listened very carefully to the words of the spirits, who gave both the masters and the people warnings and protection. Some spirits, who did not station themselves at any sites in Champasak, responded when the masters called upon them at the sacrifice. Those spirits came from far across the region and participated in the rite and a feast with the masters and the participants. The names of the spirits given by Mǭ Thīam were slightly different from those in Archaimbault’s (1959) study on the rite. It is possible to suppose, in accordance with the master’s explanation, that if the sacrifice were conducted appropriately, the spirits appeared to communicate and to protect the region. The fate of the country was fully subject to how the rites were conducted.

In the master’s discussions, remembering and forgetting fused. The past was ongoing and interwoven, and society accepted that spirits and humans lived together. In such a society, where the dead (or the past) participated with the living (or the present), history could be grasped by commemorating and appreciating the dead (past), and by worshipping spirits and narrating tales about them. Thus, although it was unknown whether the spirit of Nāng Sīdā dwelled in the stone building complex neighboring Wat Phu, it was possible to conclude that if the worship of the ancient princess continued, she continued to live in the present.

The participation of the ancient princess in present society was evidenced in the current era when Champasak became a World Heritage site. A museum was established, and many ancient artifacts, including K365, were moved there from the former palace. Many objects were added to the museum, including the statue of a woman that the local museum staff began to call Nāng Sīdā. Wishing to have a place to remember her, they placed the statue in the room next to the entrance (Fig. 2). The ancient princess, together with Kammathā, who was worshipped and commemorated at Wat Phu (Fig. 3), continued to live alongside local worshippers and pilgrims. Kammathā, whose statue took the shape of Vishnu and differed from that seen by French explorers a century ago (Aymonier 1901, 165),28) was remembered as the founder of the world. This remembrance animated his existence as living and true. In 2013, when the rite of buffalo sacrifice was reestablished by the living villagers after the authorities revoked its official suspension, Kammathā was again worshipped in the rite of sacrifice with even firmer belief in his status as a hero. Whether in this ceremonial and ritual time and space, or in the process of performance and commemoration, local true history continues to be produced and reproduced.

Fig. 2 The Statue of Nāng Sīdā and Offerings (photo by author, December 2018)

Fig. 3 People Give Offerings to the Statue, Recognizing It as Kammathā (photo by author, December 2015)

VI Conclusion

In this article, I discussed the cultural governmentality in Champasak, Southern Laos, where hybrid beliefs and facts have been produced since local beliefs first encountered modern scientific discourse. Throughout this examination, I argued that in the Southern Lao world the past and the present, the dead and the living, the material and the immaterial are participated in. In such a world, cultural governmentality is valued, and the past and its traditions are reproduced or accrue on its performing and artistic stages. In this sense, history is a living being that encourages inhabitants to live as active subjects. This ceremonial and performative art of governing is a unique, “authentic” art of the region that has transcended the borders of time and ethnicity.

If scientific discourse is indifferent to this uniqueness, or seeks to dominate the delicacy and dynamics of such a world, a competitive phase arises and ritual governmentality becomes a representation of protest against scientific governmentality. Although such ritual governmentality is a contemporary phenomenon or a product of modernity, rather than ancient surviving traditions, those who associate with it can claim the legitimacy of their governmentality as a long-lasting heritage. Accordingly, I present a multi-layered history in this article by relocating different memories in the same area. This method is important for exploring a place like Champasak, where different types of agency encounter one another. Ultimately, it is crucial to unravel the entire historical and social process, allowing a multiplicity of views and the subtlety of different selves to emerge.

Accepted: January 17, 2020

Acknowledgment

I am very grateful to all those who provided me with opportunities to conduct fieldwork in Champasak. My sincere gratitude should also go to the editors of the journal who kindly supported the review and the anonymous referees whose insightful comments were helpful for finalizing this article.

References

Archaimbault, Charles. 1972. La course de pirogues à Basăk (Čămpasăk) [Boat race in Champasak]. In La course de pirogues au Laos: Un complexe culturel [The boat race in Laos: A cultural complex], pp. 37–96. Ascona: Artibus Asiae Publishers.

―. 1971. The New Year Ceremony at Basăk (Southern Laos). Ithaca: Department of Asian Studies, Cornell University.

―. 1964. Religious Structures in Laos. Journal of the Siam Society 52(1): 57–75.

―. 1961. L’histoire de Čămpasăk [The history of Champasak]. Journal Asiatique [Asian journal] 249: 519–595.

―. 1959. The Sacrifice of the Buffalo at Vat Ph’u (Southern Laos). In Kingdom of Laos, the Land of the Million Elephants and of the White Parasol, edited by René de Berval, pp. 156–161. Saigon: France-Asie.

Aymonier, Etienne. 1901. Le région de Bassak [The region of Basak]. Le Cambodge [Cambodia], Vol. 2, pp. 157–181. Paris: E. Lerou.

Barth, Auguste. 1902. Stèle de Vat Phou près de Bassac (Laos) [The stone monument of Wat Phu near Basak (Laos)]. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 2: 235–240.

Champasak Province (Kwǣng Champāsak) ແຂວງຈຳປາສັກ. 1996. Phon ngān khǭng khōngkān samlūat vatthubūhān sathānbūhān ຜົນງານ ຂອງ ໂຄງການສຳຫຼວດ ວັດຖຸບູຮານ ສະຖານບູຮານ [Results of the project to investigate ancient objects and sites]. Champasak: Kwǣng Champāsak.

Cœdès, Georges. 1968. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia, edited by Walter F. Vella, translated by Susan Brown Cowing. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

―. 1964. Inscriptions du Cambodge [Inscriptions of Cambodia], Vol. 7. Paris: l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient.

―. 1956. Nouvelles données sur les origines du royaume Khmèr: La stèle de Văt Luong Kău près de Văt P‘hu [New data on the origins of the Khmer kingdom: The stone monument of Wat Luang Kao near Wat Phu]. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 48: 209–225.

―. 1953. Inscriptions du Cambodge [Inscriptions of Cambodia], Vol. 5. Paris: E. de Boccard.

Cole, Jennifer. 2008. Malagasy and Western Conceptions of Memory: Implications for Postcolonial Politics and the Study of Memory. Ethos 34(2): 211–243.

Comaroff, Jean. 1994. Defying Disenchantment: Reflections on Ritual, Power, and History. In Asian Visions of Authority: Religion and the Modern States of East and Southeast Asia, edited by Charles F. Keyes, Laurel Kendall, and Helen Hardacre, pp. 301–314. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

De Cesari, Chiara. 2017. Heritage between Resistance and Government in Palestine. International Journal of Middle East Studies 49(4): 747–751.

Eck, Diana L. 2012. India: A Sacred Geography. New York: Harmony Books (Kindle Version).

―. 1981. India’s “Tīrthas”: “Crossings” in Sacred Geography. History of Religions 20(4): 323–344.

Endres, Kirsten W.; and Lauser, Andrea, eds. 2012. Engaging the Spirit World: Popular Beliefs and Practices in Modern Southeast Asia. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books (Kindle Version).

Evans, Grant. 1998. The Politics of Ritual and Remembrance: Laos since 1975. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Finot, Louis. 1902. Vat Phou. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 2: 241–245.

Foucault, Michel. 1979. Governmentality. Ideology and Consciousness 6: 5–21.

Garnier, Francis. 1996. Travels in Cambodia and Part of Laos: The Mekong Exploration Commission Report (1866–1868), Vol. 1. Translated and introduced by E. J. Tips. Bangkok: White Lotus.

Geertz, Clifford. 1980. Negara: The Theater State in Nineteenth-Century Bali. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goudineau, Yves. 2001. Charles Archaimbault (1921–2001). Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 88: 6–16.

Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory, edited and translated by Lewis A. Coser. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Harmand, Jules. 2010. Explorations coloniales au Laos: Du Mékong aux Haut Plateaux, itinéraire au cœur d’une passion française [Colonial exploration in Laos: From the Mekong to the highlands, journey into the heart of a French passion]. Vientiane: Souka éditions.

Hayami Yoko. 2004. Between Hills and Plains: Power and Practice in Socio-Religious Dynamics among Karen. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

Hayami Yoko; Tanabe Akio; and Tokita-Tanabe Yumiko, eds. 2003. Gender and Modernity: Perspectives from Asia and the Pacific. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

Hayashi Yukio. 2003. Practical Buddhism among the Thai-Lao: Religion in the Making of a Region. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

Holt, John Clifford. 2009. Spirits of the Place: Buddhism and Lao Religious Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Jacques, Claude. 1962. Notes sur l’inscription de la stèle de Văt Luong Kău [Notes on the inscription of the stone monument of Wat Luang Kao]. Journal Asiatique [Asian journal] 250(2): 249–256.

Kanya Wattanagun. 2017. Karma versus Magic: Dissonance and Syncretism in Vernacular Thai Buddhism. Southeast Asian Studies 6(1): 115–137.

Ladwig, Patrice. 2012. Can Things Reach the Dead? The Ontological Status of Objects and the Study of Lao Buddhist Rituals for the Spirits of the Deceased. In Engaging the Spirit World: Popular Beliefs and Practices in Modern Southeast Asia, edited by Kirsten W. Endres and Andrea Lauser. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books (Kindle Version).

Le Boulanger, Paul. 1931. Histoire du Laos Français: Essai d’une étude chronologique des principautés laotiennes [History of French Laos: A tentative chronological study of the Laotian principalities]. Paris: Plon.

Lemoine, Jacques. 2001. L’œuvre de Charles Archaimbault (1921–2001) [The work of Charles Archaimbault (1921–2001)]. Aséanie 7: 169–184.

Lévi-Bruhl, Lucien. 1984 (1926). How Natives Think. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Lévy, Paul. 1959. The Sacrifice of the Buffalo and the Forecast of the Weather in Vientiane. In Kingdom of Laos: The Land of the Million Elephants and of the White Parasol, edited by René de Berval, pp. 163–173. Saigon: France-Asie.

Lukas, Helmut. 2012. Ritual as a Means of Social Reproduction? Comparisons in Continental South-East Asia: The Lao-Kmhmu Relationship. In Ritual, Conflict and Consensus: Case Studies from Asia and Europe, edited by Gabriela Kiliánová, Christian Jahoda, and Michaela Ferencová, pp. 103–117. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press.

Lunet de Lanjonquière, Étienne Edmond. 1907. Inventaire descriptif des monuments du Cambodge [Descriptive inventory of the monuments of Cambodia], Vol. 2. Paris: Impremerie Nationale.

Marchal, Henri (Hangrī Māksān) ຮັງຣີ ມາກຊານ. 1959. Phāsāt hīn Vatphū khwǣng Champāsak ຜາສາດຫີນວັດພູ ແຂວງຈຳປາສັກ [Wat Phu stone palace, Champasak Province]. Translated by Phanyā Unhū’an Nōrasing and Chao Bun Oū’a Nā Champāsak ພະຍາ ອຸນເຮືອນ ນໍຣະສິງ ແລະ ເຈົ້າ ບຸນເອື້ອ ນາຈຳປາສັກ. Vientiane: Ministry of Religion, Kingdom of Laos.

―. 1957. Le temple de Vat Phou: Province de Champasak [Wat Phu Temple: Champasak Province]. Édition du département des cultes du Gouvernement Royal du Laos [Edition of the Department of Religions, Royal Lao Government]. Saigon: Imprimerie nouvelle d’Extrême-Orient.

McDaniel, Justin Thomas. 2014. The Lovelorn Ghost and the Magical Monk: Practicing Buddhism in Modern Thailand. New York: Columbia University Press.

Nginn, Pierre S. 1967. Les fêtes profanes et religieuses au Laos [Secular and religious festivals in Laos]. 2ème edition [Second edition]. Vientiane: Éditions du comité litteraire.

Ong, Aihwa. 1987. Spirits of Resistance and Capitalist Discipline: Factory Women in Malaysia. New York: State University of New York Press.

Parmentier, Henri. 1914. Le temple de Vat Phu [The temple of Wat Phu]. Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 14(2): 132.

Pattana Kitiarsa. 2005. Beyond Syncretism: Hybridization of Popular Religion in Contemporary Thailand. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 36(3): 461–487.

Picanon, Eugène. 1901. Le Laos Français [French Laos]. Paris: Augustin Challamel.

Platenkamp, Jos D. M. 2008. The Canoe Racing Ritual of Luang Prabang. Social Analysis 52(3): 1–32.

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes. New York: Routledge.

Rappaport, Joanne. 1998. The Politics of Memory. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Rehbein, Boike. 2007. Globalization, Culture, and Society in Laos. London and New York: Routledge.

Said, Edward W. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: A.A. Knopf.

Shaw, Rosalind. 2008. Displacing Violence: Making Pentecostal Memory in Postwar Sierra Leone. Cultural Anthropology 22(1): 66–93.

Smith, Laurajane; and Akagawa Natsuko, eds. 2009. Intangible Heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

Stuart-Fox, Martin. 2001 (1992). Historical Dictionary of Laos. Second Edition. Lanham: Scarecrow Press.

―. 1997. A History of Laos. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja. 1976. World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a Historical Background. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tanabe Shigeharu; and Keyes, Charles F., eds. 2002. Cultural Crisis and Social Memory: Modernity and Identity in Thailand and Laos. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Tournier, M. A. A. 1900. Notice sur le Laos Français [An account of French Laos]. Hanoi: E.-H. Schneider.

Worsley, Peter ワースレイ,ピーター. 1981. Sennen okoku to mikai shakai: Meraneshia no kago karuto undo 千年王国と未開社会―メラネシアのカーゴ・カルト運動 [The trumpet shall sound: A study of “cargo” cults in Melanesia]. Translated by Yoshida Masanori 吉田正紀. Tokyo: Kinokuniya Shoten. Originally published as The Trumpet Shall Sound: A Study of ‘Cargo’ Cults in Melanesia (London: Granada Publishing Ltd., 1957).

1) In Lao, Wat Phu means “mountain temple,” and the site is located at the bottom of the mountain Phū Kao. Phū Kao means “mountain in the shape of a woman’s chignon.” Ancient inscriptions, however, seem to refer to the mountain as Lingaparvata (“mountain in the shape of a lingam,” or phallus, a symbol of Shiva).

2) The buffer zone of the Champasak World Heritage site includes not only Wat Phu, but also the mountains and archaeological sites located nearby, particularly the Ancient City (called Kuruksetra or Sresthapura).

3) In addition to the data collected in the early 2000s, I use two photos taken during short visits in 2015 and 2018.

4) I read the text in Japanese translation.