Contents>> Vol. 11, No. 2

Malaysia’s New Economic Policy: Fifty Years of Polarization and Impasse

Hwok-Aun Lee*

*ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace, Singapore 119614

e-mail: lee_hwok_aun[at]iseas.edu.sg

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4513-5235

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4513-5235

DOI: 10.20495/seas.11.2_299

The New Economic Policy has transformed Malaysia since 1971. Pro-Bumiputera affirmative action has been intensively pursued and continuously faced pushback. This paper revisits three key junctures in the NEP’s fifty-year history that heightened policy debates—and the ensuing persistent polarization and stalemate in policy discourses. First, at its inception in the early 1970s, despite substantial clarity in its two-pronged poverty alleviation and social restructuring structure, the NEP was marred by gaps and omissions, notably its ambiguity on policy mechanisms and long-term implications, and inordinate emphasis on Bumiputera equity ownership. Broader discourses have imbibed these elements, and they tend to be more selective than systematic in policy critique. Second, during the late 1980s, rousing deliberations on the successor to the NEP settled on a growth-oriented strategy that basically retained the NEP framework and extended ethnicity-driven compromises. Third, since 2010, notions of reform and alternatives to the NEP’s affirmative action program have been propagated, which despite bold proclamations again amount to partial and selective—not comprehensive—change. Affirmative action presently drifts along, with minor modifications and incoherent reform rhetoric stemming from conflation of the NEP’s two prongs. Breaking out of the prevailing polarization and impasse requires a systematic and constructive rethink.

Keywords: Malaysia, New Economic Policy, affirmative action, ethnicity

Introduction

The year 2021 marked the fiftieth anniversary of Malaysia’s New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP reconfigured Malaysia’s political economy and, most pivotally, cemented pro-Bumiputera affirmative action—preferential programs to promote the majority group’s participation in higher education, high-level occupations, enterprise management and control, and wealth ownership. During the policy’s official phase of 1971–90, the Malaysian government implemented vast affirmative action programs; but the NEP also provided the imprimatur for myriad interventions long beyond that time frame. The Bumiputera category, comprising about 70 percent of Malaysia’s current citizen population, consists of Malays (56 percent) and other indigenous groups (14 percent).

While everyone readily agrees that the NEP fundamentally transformed Malaysia, opinion toward its enduring presence is polarized and stalemated. Advocates assert that the NEP achieved tremendous success but remains unfinished business; detractors vouch that the NEP largely failed and has overstayed beyond its expiry date. This historical milestone presents an opportunity to re-appreciate the NEP’s strengths, critically review its contents, and revisit its passage across time. The NEP judiciously distinguished its core elements of eradicating poverty and social restructuring, which pursued distinct objectives through distinct policy instruments. However, its framework was also marred by gaps and omissions, and popular and academic discourses have tended to reproduce the official framework or to make minor modifications branded as major changes, hindering the formulation of coherent solutions and perpetuating policy impasse. Current debates largely fudge, rather than confront, the complex challenge of preferential policies.

This paper examines the contorted state of NEP-related discourses through the lenses of three key junctures in the policy’s history. First, although the NEP set out a well-crafted two-pronged strategy, it also shaped policy discourses through major omissions and biases: ambiguity on policy mechanisms, ultimate objectives, and the implications of attaining targets; demarcation of domains for applying ethnic quotas; inordinate emphasis on Bumiputera equity ownership; and overstatement of the role of economic growth in providing opportunity and the unattainable assurance that no group would feel deprived.

Second, policy debates flourished as Malaysia neared 1990, especially within the National Economic Consultative Council (NECC), which made proposals for the NEP’s successor. The NECC report, and the official decade-long road map termed the National Development Policy (NDP) (1991–2000), retained the NEP’s core, including the above-mentioned omissions, while couching the overarching agenda as “growth with equity.” While the private sector was designated a more important role and investment conditions were selectively liberalized, the Bumiputera—especially Malay capitalist—development agenda actually intensified, while economic growth and private higher education placated minority discontent.

Third, another twenty years later, a “new economic muddle” mainstreamed misguided policy alternatives and false promises of change, engendering a peculiar state of affairs surrounding the NEP’s second prong. The New Economic Model (NEM) of 2010 proposed refashioning affirmative action in a nebulous “market-friendly” manner taking into account “need” and “merit.” While the NEM effectively involved selective tweaks and modifications, it projected itself as a bold departure from the extant race-based preferential treatment. A fierce backlash ensued, which the government assuaged by introducing a Bumiputera economic transformation program. The program’s emphasis on dynamic Bumiputera SMEs was timely and reasonable, although—like the NEM—it involved selective interventions, not systemic transformation. Policy rhetoric continually propagates sweeping statements on how Malaysia should conduct affirmative action on the basis of “need” instead of race, omitting rigorous scrutiny of pro-Bumiputera programs. These discourses conflate poverty alleviation with affirmative action, and they perpetuate both muddled perspectives and misplaced expectations of reform.

This paper proceeds with three main segments. The first revisits and critiques the original NEP debates and the program’s reception in the early to mid-1970s; the second unpacks the NECC-NDP deliberations and outcomes of the late 1980s and early 1990s; the third assesses the debates of the past decade prompted by the NEM. The paper traces out conceptual, practical, and political factors that help explain the NEP’s trajectory. Conceptually, the NEP’s gaps and omissions have been retained while its cogent two-pronged structure has faded from collective consciousness. Practically, discourses on affirmative action outcomes and implications have fixated on quantitative targets and monolithic deadlines instead of the capability and readiness of Bumiputeras to undertake change, and opted for simplistic platitudes rather than systematic alternatives that integrate identity, need, and merit. Politically, UMNO has continuously applied pressure, with occasional fiery bursts, to retain preferential treatment for Bumiputeras. However, the current situation is also characterized by political postures on all sides that ultimately evade rather than resolve the problems. The paper concludes with some suggestions for a more systematic and constructive approach for Malaysia to move beyond fifty years of polarization and impasse on the NEP, involving a fundamental shift from the two prongs of poverty reduction and social restructuring to the principles of equality and fairness.

The New Economic Policy at Birth: Foundations and Enduring Precedents

The “Two Prongs”: Compromise and Clarity

The natural and seemingly familiar starting point is the New Economic Policy’s original wording. This inquiry undertakes a fresh and direct reading of the relevant policy documents, in view of popular and academic discourses on the NEP that have tended to reproduce abridged versions or relied on secondhand and partial recollections. The literature generally upholds the NEP’s noble goal of national unity, its two-pronged framework, and its assurances to minority groups, but it also tends to limit the analysis to these rudiments, omitting policy specifics.

The fiftieth anniversary is an opportune moment to revisit the process of compromise through which the NEP was forged, and to re-appreciate the clarity of its two-pronged structure. We should note that the policy emerged as part of a continuum. Demands for more proactive promotion of Bumiputera industry and commerce had intensified in the latter 1960s, notably with the First and Second Bumiputera Congress in 1965 and 1968, which made extensive proposals and spurred some change; but the Tunku Abdul Rahman administration did not systemically waver from its laissez-faire dispensation (Osman-Rani 1990).

The communal violence of May 13, 1969 traumatized the nation and catalyzed a fundamental policy break. Just Faaland’s influence is evident, most pivotally in centralizing the problem of racial imbalances. In a paper written mere weeks after May 13, Faaland decried that the

current ad hocism of economic policy discussion and decision-making badly needs to be replaced by analysis and consideration of the framework and means of a policy that is relevant to the basic issues of racial balance in economic development and growth. (Faaland 1969a, 247)

The NEP would adopt Faaland’s conceptual framework—including a typology of modern versus traditional sectors—which attributed sociopolitical instabilities to interracial imbalances in employment, income, and ownership. Labor market stratification encapsulated the problem: Bumiputeras largely occupied lower-rung jobs, predominantly in the rural and traditional sectors; their participation was acutely low in professional and managerial positions, and in the urban and modern sectors (Faaland 1969a; 1969b).

The policy agenda was contested. Just Faaland, Jack Parkinson, and Rais Saniman’s (1990) substantive account of the NEP formulation process offers invaluable firsthand insight, albeit with discernible self-evaluation bias. By this account, the “EPU School,” representing the Economic Planning Unit (EPU) and sections of the bureaucratic-political establishment, advocated for growth-centric, market-driven, indirect approaches to resolving racial disparities. In marked contrast, the newly formed Department of National Unity (DNU) pressed for redistribution, through robust state intervention, to redress racial imbalances proactively and directly.

The personal affinity of the “DNU School” with Prime Minister Razak, and its resonance with his ideological leanings, gave it the upper hand (Kamal 2019). Nonetheless, the emergence of the NEP’s core elements, and the implications of continual policy mindsets and discourses, warrant a deeper look. Another internally circulated paper by Faaland (1969b) set a more forceful tone. Among the central features of national strategy, Faaland listed in first place that Malaysia should “emphasize racial balance over national growth.” The second item tempered that proposition by calling for balanced racial participation in the modern economy instead of redistribution from non-Malays to Malays.

Nonetheless, the lines were drawn, which generated concern over the zealousness of racial redistribution. A March 18, 1970 document titled “The New Economic Policy,” issued by the DNU as a directive to all government departments and agencies in formulating the Second Malaysia Plan, stipulated three main objectives: (1) reduction of racial economic disparities; (2) creation of employment opportunities; and (3) promotion of overall economic growth. The DNU also declared, rather pugnaciously, “the Government is determined that the reduction in racial economic disparities should be the overriding target even if unforeseen developments occur which pose a harsher conflict than now foreseen between the three objectives” (DNU 1970, 310; italics in original).

Such assertions expectedly triggered pushback. Within the bureaucracy, EPU Director-General Thong Yaw Hong was moved to counterbalance what he characterized as “extreme interventionist measures” (Heng 1997).1) Through subsequent deliberations, the poverty reduction “irrespective of race” and “no group will feel any sense of deprivation” provisos were inserted, evidently with the intention to safeguard minority group interests. The eventual articulation of the NEP’s vision and framework, as a nine-page Chapter 1, “The New Development Strategy,” in the Second Malaysia Plan (Malaysia 1971) embodied these ethnicity-driven compromises. The rhetoric of racial disparities and primacy of redistribution were toned down.

The NEP declared national unity as its overarching goal and established its “two-pronged” core objectives of poverty eradication irrespective of race, and accelerating social restructuring in order to reduce and eventually eliminate the identification of race with economic function. Widespread poverty, unemployment and underdevelopment, and disparities between race groups were identified as major threats to socioeconomic stability.

The two prongs have recycled in the collective consciousness for half a century. A combination of over-familiarity and ad nauseam recitation have perhaps eroded appreciation for the judicious distinction of objectives and instruments encapsulated in the two prongs. The NEP affirmed, albeit implicitly, the basic and noble principle that the poor and vulnerable of all groups deserved to be assisted on the basis of equality and dignity. Ethnic identity had no part in the provision of basic needs and in helping all Malaysians attain a minimal standard of living. Racial disparities featured as the problem addressed in the second prong: the identification of race with economic function.

The NEP also emphasized that the two prongs were “inter-dependent and mutually reinforcing,” noting that they operated in tandem rather than as replacements for each other (Malaysia 1971, 3). The first would focus on raising productivity, structural change (movement into modern sectors), infrastructure, utilities, education, and social services. The second encompassed modernization of rural economies and “rapid and balanced growth of urban activities,” education and training, and “above all, ensure the creation of a [Bumiputera]2) commercial and industrial community in all categories and at all levels of operation” (Malaysia 1971, 4–6). The NEP grasped that the first and second prongs pursued distinct objectives that called for distinct policy instruments. In other words, the objectives of the second prong could not be achieved by using the instruments of the first.

Gaps and Omissions

Undoubtedly, it is difficult to disagree with the NEP’s cornerstones. But a tendency to zealously embrace them has also caused the program’s outstanding strengths to be under-appreciated and its subtle gaps and omissions to be overlooked. The NEP was inadequate in three crucial areas.

First, it insufficiently specified policy mechanisms and limits. Most consequentially, the NEP failed to appreciate the salience of Bumiputera preferential treatment to the second prong, and its application in sectors with finite opportunity. Social restructuring was contingent on Bumiputeras’ accelerated progress in higher education, upward occupational mobility, and owning and operating of enterprises. It was clearly foreseeable, but scantly acknowledged, that ethnic quotas or other forms of preferential treatment would feature centrally in pursuit of the second prong. Public institutions would also be the primary vehicles: public universities, public sector employment, public finance institutions, and state-owned enterprises (Lee 2021a).

Recognition of preferential treatment would also add urgency to the need to develop capability, competitiveness, and confidence. Awareness of the scope and scale of these interventions would attune the policy discourses to the reality that economic growth, no matter how rapid, still entailed finite resources to be allocated among contending groups. Instead, the NEP settled on an overpromise: “in the implementation of this Policy, the Government will ensure that no particular group will experience any loss or feel any sense of deprivation” (Malaysia 1971, 1). This phrase, which emerged not out of philosophical premises but as an ethnically driven compromise, would be a constant focal point of policy debates. A growing economy can continually generate employment and economic opportunity in the private sector. However, Malaysia’s affirmative action operates predominantly in public institutions—notably, public university enrollment, public sector employment, or public procurement—where opportunities are limited; and hence redistribution in favor of Bumiputeras cannot avoid some degree of non-Bumiputera exclusion, even if the economy keeps growing.

It may be wishful to expect the NEP to openly acknowledge that Bumiputera preferential treatment was its core element, and that the allocation of finite opportunities would inevitably come at some expense to other groups. But it is evident that the NEP’s circumvention of these precepts, intentionally or otherwise, induced misguided thinking and perpetuated policy clashes. NEP advocates believed that a growing economy would assuage minority discontent; detractors highlighted unequal access as a broken promise. Both sides continually talked past each other.

Indeed, by the mid-1970s the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and Gerakan while assessing the Third Malaysia Plan markedly invoked the NEP promise that no group would experience any loss or sense of deprivation. Mandated transfers of existing private sector equity clearly violated the promise that only newly created wealth would be affected, but the “no deprivation” provision was taken to apply across the board.3) In MCA President Lee San Choon’s words:

. . . we welcome the fact that this assurance has now been repeated in the Third Malaysia Plan and we trust that it will be adhered to in spirit as well as in substance. Indeed, if we can achieve our targets for the rapid growth and expansion of the economy, there need be no cause to fear that this assurance will be compromised. (Lee 1976, 4)

Predictably, there was a recurrence of minority grievance over perceived unfair opportunities to enter public university.

The second inadequacy of the NEP was that it was opaque and noncommittal about the implications of its timeline and targets. The time frame of 1971–90 and key targets were clear enough. By 1990, occupations at all levels and in all industries would reflect the national racial composition, and Bumiputeras would own 30 percent of equity. But the overarching goal for the community was obfuscated. The NEP’s “within one generation” aspirations, coterminous with a twenty-year outlook, provided some hints. The 1971 version framed this generational goal as the Bumiputeras becoming “full partners in the economic life of the nation” (Malaysia 1971, 1). The ambition could be taken as a resolve for Bumiputeras to be co-equal and, by implication, self-reliant. The magnitude of the challenge was acknowledged. The Second Malaysia Plan noted that some goals, especially the creation of a Bumiputera Commercial and Industrial Community (BCIC), might take longer than one generation to achieve (Malaysia 1971, 9).

Unfortunately, this astute observation was made in a passing and obscure manner. The NEP’s full-fledged version rolled out in 1976, as a forty-page Chapter 4, “Outline Perspective Plan, 1971–90,” in the Third Malaysia Plan (Malaysia 1976).4) This detailed development program reduced the generational goal from Bumiputera full economic partnership to Bumiputera ownership of 30 percent of equity. It also refrained from evaluating whether the 1990 timeline was adequate and from expanding on a sector-by-sector approach with differentiated timelines for higher education, employment, enterprise development, and ownership (Malaysia 1976). The vast range of interventions that rolled out logically required customized timelines and specific modifications over time. Policy documents allowed expectations of one monolithic expiry date to become ingrained. In reality, the vast range of affirmative action rolled out in piecemeal fashion; and it did not simultaneously start in 1971, but discussions around policy termination or continuity, which would later converge in 1990, took a monolithic stance in which either all affirmative action would continue or all would cease.

Furthermore, the implications of reaching the targets were not methodically outlined. Policy targets crucially provide the grounds for evaluation and revision, but the complexities of Bumiputera preferential programs required more sophisticated formulation—most saliently, to account for the beneficiary group’s capacity and confidence to undertake change. The NEP implied that hitting targets or reaching 1990 would constitute the basis for deliberating policy dissolution or continuity, without considering whether passing those thresholds automatically signalled the readiness and willingness of the Bumiputera population to do so—particularly since such change entailed some attenuation of privileged access. These longer-term and deeper aspects of affirmative action were not broached. Silence on this front permitted solidification of the view that decisions regarding continuation or termination of the NEP hinged solely on time limits and on national performance vis-à-vis numerical targets, especially 30 percent Bumiputera equity ownership.

The third shortcoming of the NEP was that in terms of the apportionment of emphasis and priority, it gave relatively less prominence to education and placed inordinate emphasis on equity ownership. The driving goal was twofold:

. . . employment in the various sectors of the economy and employment at all occupational levels should reflect the racial composition of the country by 1990; the ownership of productive wealth should be restructured so that by 1990 the Malays and other indigenous people own and operate at least 30% of the total. (Malaysia 1976, 76)

Of the eight main objectives—related to employment, productivity, income, modernization, urbanization, BCIC—only one, the last on the list, directly addressed higher education: “expansion of education and training facilities, other social services and the physical infrastructure of the country to effectively support the attainment of the above objectives” (Malaysia 1976, 51–52).

Why did the NEP follow its particular course? Three plausible reasons warrant a brief discussion. First, the NEP, although a clear breakthrough in breadth and ambition, was at heart a continuation of norms already established in Malaysia. The special position for Bumiputeras and the practice of reservation derived from the independence constitution’s Article 153 and became implicitly embedded as policy underpinnings. Specifically, the Malaysian government negotiated the allocation of socioeconomic opportunity not on principles of equality, preferential treatment, and fairness but through an ethnic framing of majority-versus-minority interests and a sectoral bifurcation of public sector intervention versus relative restraint in private sector affairs. Even while drawing a clear contrast between the first prong—which would apply “irrespective of race”—and the second prong—which would address “identification of race with economic function”—the NEP omitted the race-based preferential treatment that was operationally integral to the second prong. Malaysia’s relative insouciance toward racial quotas arguably resulted from such policy measures becoming normalized within public institutions.

Second, the NEP mirrored the Alliance-Barisan Nasional mode of representation and negotiation of ethnic interests. R. S. Milne characterized the NEP as “a restatement of the ‘bargain’ between the races” (Milne 1976, 239). The ruling coalition had established norms for reaching settlements among constituent Malay, Chinese, and Indian parties. In a similar vein, personal interventions representing ethnic interests secured commitments to inclusivity in the NEP—but they also perpetuated the practice of bargaining for ethnically defined concessions rather than substantively deliberating the balance of preference and equality.5) In the face of intense pressures for Bumiputera economic advancement, especially in equity ownership, the minority group stance was understandably to resist over-encroachment.6) Perhaps because tensions had heightened, the eventual compromises were greeted with a sense that the various communities should move on. Additionally, ethnicity-based targets seemingly provided clear grounds to debate policy continuation or termination.

Third, politics weighed in. The NEP was as much a political project as it was economic, but political interests and pressures shaped it in a few consequential ways. Subtle differences between the 1971 and 1976 versions speak volumes. Faaland et al. (1990) observe that the 1971 NEP articulation was more restrained in terms of targeting, mainly due to pressures from parties concerned that the policy was too aggressive. Heng Pek Koon (1997, 268) documents how Finance Minister and MCA President Tan Siew Sin resisted mandatory measures to relinquish equity until illness compelled him to resign in 1974. By 1975, policy had momentously swung in the opposite direction, evidenced by an increasingly assertive tone and incorporation of clear targets. In some ways, change was taking place regardless of the policy articulation. Notably, even while the Industrial Coordination Act (ICA), which mandated Bumiputera equity allocations, was passed, the Outline Perspective Plan provided an assurance that “Individual companies therefore will not be required to redistribute their existing equity to any significant extent. This underlies the policy that there will not be compulsory divestment on the part of individual enterprises” (Malaysia 1976, 85). The escalation of political pressure toward the mid-1970s raised concern that the government might accelerate the 30 percent target to an earlier date, which required extensive encroachment on private, especially Chinese, ownership (Gerakan Rakyat 1976).7)

New Economic Policy to National Development Policy: Change in Form, Continuity in Substance

Debates on the NEP heightened in the 1980s. The preceding decade had witnessed recurring discontent toward the NEP, especially in terms of non-Bumiputera access to public higher education and the pursuit of Bumiputera equity ownership. Alternatives to public university were limited, and the issue was compounded by perennial delays of approval for the proposed Merdeka University, the MCA’s flagship higher education institution. A 1984 seminar, convened by the Barisan Nasional (BN) component party Gerakan to analyze NEP achievements and propose alternatives, presented alternate estimates of Bumiputera equity ownership that showed the 30 percent threshold had been surpassed, corroborating the case for the NEP’s second prong to be terminated beyond 1990. On education and employment, Party President Lim Keng Yaik went so far as to say that the “rigid quota system” had vastly promoted Bumiputera upward mobility but deprived “many young and qualified non-Bumiputeras,” and that the government must bring the “racial quota system . . . to an end as quickly as possible” (Gerakan 1984, 157). The seminar concluded by adopting a set of resolutions for a post-1990 revised NEP that would, first and foremost, emphasize economic growth, national unity, and poverty eradication irrespective of race—in other words, Gerakan supported the NEP’s first prong but not the second (Gerakan 1984, 215). Notably, the party’s Economic Bureau made the case for “channelling of resources to groups on the basis of their economic needs rather than on the basis of ethnicity” (Gerakan 1984, 206). Likewise, Lim Lin Lean, reflecting the MCA’s disposition a few years later, argued that “economic need rather than ethnicity should be the overriding basis of future resource allocation” (Lim 1988, 55).

In the late 1980s the general disposition toward the NEP, backed by official statistical projections, was that the program was on track to reach the poverty reduction target of 17 percent by 1990 but would fall short on social restructuring. Behind the scenes, some rethinking was taking place. While drafting the Sixth Malaysia Plan, the EPU was attempting to steer the policy focus toward human resource development.8) It was apparent that rent distribution and accelerated promotion of inexperienced Malays into corporate management, whether in the form of equity, contracts, or licenses, tended to breed patronage and rent-seeking, most starkly the “Ali Baba” liaisons in which a politically connected Malay secured a contract and outsourced the work to a non-Malay, typically Chinese, partner.

An economic vision rooted in human resource development potentially could have inclined the system toward more productive rather than acquisitive interventions, but it remains unclear whether the scope, limits, and implications of Bumiputera preferential treatment would have been systematically acknowledged and integrated into the planning process. The Mid-term Review of the Fifth Malaysia Plan (1989) provides a hint of this prospective shift toward human resource development, involving employment, skills, and productivity, implicitly contrasted to wealth acquisition and rent-seeking:

Industrial restructuring will continue to be the main thrust of future development . . . [requiring] a coordinated package of policies that simultaneously address the improvement of manpower skills, research and development, and a reemphasis of good work ethics and attitudes. (Malaysia 1989, 6)

However, it is doubtful whether the national policy to succeed the NEP would have systematically addressed Bumiputera development and presented a comprehensive plan that could replace the NEP, since the Mid-term Review relegated the crucial sphere of university enrollment to the 13th, and very last, chapter, titled “Social Services” (Malaysia 1989).9)

Various conditions set the stage for a more growth-oriented and private sector-driven agenda (Kamal and Zainal Aznam 1989)—but in ways that under-declared the continuing, even expanding, redistributive thrust of national development policy. From the mid-1980s, with corporate-leaning Daim Zainuddin as finance minister and in response to economic recession and public debt concerns, coupled with the advent of massive FDI outflows from Japan and Northeast Asia, Malaysia’s economic policy gravitated toward private investment-driven growth. These developments widened the gates for the privatization project, which reconfigured Malaysia’s political economy in a general sense, and specifically as the vehicle for the BCIC. Some unease lingered in the Malay community from fiscal austerity and a government hiring freeze. Nonetheless, the boom was under way; real GDP galloped at 9.3 percent annual growth in 1987–90, compared to 4.6 percent for 1980–87.

A broadly deliberative policy formulation process commenced in the context of an increasingly buoyant economy—and a fraught political milieu. Power struggles within UMNO, social tension, and democratic distress, compounded by escalating Malay nationalist sentiments, put Malaysia on edge. Prime Minister Mahathir, having marginally prevailed in UMNO’s controversial 1987 party elections and gained ignominy for the Operasi Lalang detention without trial of 108 opposition leaders and social activists, forged on with a pro-Malay program aligned with his predilections as the nation approached 1990, while also striking a conciliatory note. The calls for establishing a national forum originated from MCA but eventually gained wider traction and added weight in political calculations (Ho 1992; Jomo 1994). Ghafar Baba, as the newly ascendant deputy prime minister, demonstrated a shared burden with Mahathir toward the need to broaden support.10)

The National Economic Consultative Council was formed in January 1989, comprising 150 members, with a 50-50 Bumiputera-non-Bumiputera split and diverse representation of political parties and civil society. The NECC evaluated the NEP’s progress and discussed policies that should succeed it. Most discussions proceeded amenably, but the discussions under the “social restructuring” working group were heavily contested, even acrimonious, resulting in some walkouts.11) The mood reflected the high stakes and polarized zeitgeist.

The NECC culminated with the February 1991 delivery of a hefty report, the “Economic Policy for National Development,” widely known by its Malay acronym DEPAN (Dasar Ekonomi untuk Pembangunan Negara). DEPAN provided an extensive evaluation of the NEP, in terms of the distribution of benefits and the contrasting experiences and perceptions of the majority and minority groups: Bumiputeras’ anxiety toward their disadvantaged economic situation that may leave them continually straggling, and non-Bumiputeras’ unease at unequal opportunity and their place in Malaysia. The report acknowledged the discontent of non-Bumiputeras over unequal access to higher education as well as of Bumiputeras over lack of business opportunities and shortcomings in Bumiputera entrepreneurship (Malaysia, NECC 1991). It recognized the concept of social justice while cautioning against privatization and the various pitfalls of rent-seeking (Jomo 1994).

However, DEPAN would have benefited from more rigorous analyses of the preferential system and how effectively and equitably it was enabling the Bumiputeras. Among the gaps were its rather routine treatment of education and training, which reported Bumiputera proportions in diploma and degree programs but scarcely ventured into the roles and shortcomings of affirmative action in engendering these outcomes. Education was also overshadowed by a preponderant focus on Bumiputera equity ownership and employment as the most consequential outcomes of the NEP (Malaysia, NECC 1991, 77–80, 110–120). DEPAN’s call for official data transparency, while commendable, was wedded to the common but misplaced view that achieving targets entailed terminating policies—and thus better data would facilitate concrete reform. It omitted evaluation of the capacity and confidence of the Bumiputera population to undertake modifications or curtailment of preferential treatment, and offered few specifics on alternate mechanisms besides quotas.

The NECC did not supplant institutionalized development planning under the EPU, but the EPU witnessed its proceedings and served as the secretariat for the DEPAN report. Although some proposals were not taken up, most prominently the formation of a National Unity Commission to oversee policy implementation, the pillars of DEPAN and the Second Outline Perspective Plan, more widely known as the National Development Policy (NDP), bore a close resemblance to each other. Both propagated variations of “balanced development” and “growth with equity,” and both recommitted to the NEP (Malaysia 1991, 4–5; Malaysia, NECC 1991, 180–181). In view of Malaysia’s political milieu, the NDP treaded delicately on redistribution, couching policy objectives in more discreet terms although the agenda would continually grow, especially with privatization already under way, marshalled by Finance Minister Daim Zainuddin with Mahathir’s blessing.

It is a fair generalization to say that the NDP took Malaysia on a more growth-oriented path in the 1990s, but this in no way diminished the vigor of redistributive measures. MCA President Ling Liong Sik, in a 1991 speech expressing support for the NDP, asserted that the “principle of just and fair accommodation and compromise amongst all races must be regarded as a basic tenet of government” (Ling 1995, 112). The cautious undertone perceivably derived from the NDP’s ambiguity of policy targets and timelines, which was a major point of contention.

However, the more consequential omission of the NDP was not that it lacked firm targets—unlike the NEP’s 30 percent Bumiputera equity ownership and proportionality in employment—but that it sidestepped a full account of the myriad ways pro-Bumiputera policies would persist or expand (Lee 2021b). It also neglected to give attention to possibilities for preferential treatment to be rolled back or transitioned to a system less dependent on overt ethnic quotas. Soon after commencing an ostensibly growth-oriented policy in 1991, the Amanah Saham Bumiputera unit trust scheme was launched, and the microfinance institutions Tekun and Perbadanan Usahawan Nasional Berhad (PUNB; National Entrepreneurship Corporation Limited) were founded, while Majlis Amanah Rakyat (MARA; Council of Trust for the People) continued its vast Bumiputera-only programs in education and entrepreneurship, Bumiputera preference in public procurement forged ahead, and affirmative action in public higher education continually expanded.

The BCIC took center stage, and along with privatization it would be a defining development of the 1990s (Thillainathan and Cheong 2016; Chin and Teh 2017). A further appeal of the policy was that the equity to be redistributed would not take away from existing Chinese or foreign companies.12) But the NDP retained the NEP-rooted sweeping generalization that economic growth, “new” wealth redistribution, and income gains signified that minorities were not deprived of opportunity. Even Zainal Aznam (2012), while proving his intimate knowledge of Malaysia’s policy regime and its outcomes, only touched on the ways in which redistributive requirements in corporate ownership and employment were implemented flexibly and predominantly on new equity or new recruitment, and omitted the foremost non-Bumiputera complaint—unequal access to public higher education admissions and government scholarships.

Ultimately, the decisive theme was not the scope and means of maintaining Bumiputera preferential treatment and the capacity of the community to grapple with change, but whether or not to keep ethnic quotas (Means 1990). The NDP succeeded the NEP on the grounds that Malaysia had not attained the NEP’s mission, but the case was made in a selective and incomplete manner. Attention fixated on how Bumiputera equity ownership fell short of the 30 percent target—but in other programs that had reached or superseded targets, e.g., public sector employment and public university enrollment, there was minimal policy deliberation on the possibility of modifying or rolling back Bumiputera preferential treatment. Vision 2020, Mahathir’s evocative and galvanizing mission statement presented in 1991, was more forthright:

If we want to build an equitable society then we must accept some affirmative action. . . . By legitimate means we must ensure a fair balance with regard to the professions and all the major categories of employment. But we must ensure the healthy development of a viable and robust Bumiputera commercial and industrial community. (Mahathir 1991)

The thirty-year aspiration was couched in terms of “fully competitive Bumiputeras, on par with non-Bumiputeras” (Mahathir 1991). However, there was no meaningful follow-through on this quest for parity. A Vision 2020 national convention in December 1991, in which policy strategies and some action plans were discussed, steered clear of the Bumiputera agenda (SERU 1992).

Why did the NDP take shape the way it did? First, it essentially retained the NEP template, hence extending the latter’s gaps and omissions. The NDP continued to: (1) neglect systematic engagement with the preferential mechanisms undergirding the NEP’s second prong and with the implications of reaching policy targets; (2) demarcate domains for such programs (predominantly in public institutions and the public sector) and other domains that were relatively exempted from redistributive requirements (predominantly in the private sector); (3) perpetuate the panacea of economic growth for resolving distributive conflicts and assuaging minority discontent (Malaysia 1991). The new dispensation would augment private sector opportunities, but the public sector remained a domain of marked Bumiputera preference that invariably entailed some exclusion of minorities. Rapid economic growth and the expansion of private tertiary education did eventually allay tensions, but by circumvention rather than reconciliation.

Tellingly, affirmative action based on merit and need was broached again by the MCA in 1989 but failed to gain traction and was eventually conceded (Osman-Rani 1990). The notion was emotively resonant, but it was negated by its ambiguity and confinement to an oversimplistic race-vs-merit/need dichotomy, with little consideration of blending merit-based and need-based selection with continual consideration of ethnic representation, particularly in public universities. Limited to these binaries, ethnic quotas were eventually retained partly due to a realization that non-Malay students would be more assured of university spaces under an ethnic quota than an income-based quota.13) Merit- and need-based affirmative action dissolved due to political resistance and pragmatism in maintaining the status quo, but also due to the superficiality of these purported alternatives to race-based affirmative action.

Second, the consultative approach, and veiling of the redistributive agenda, sought to broaden the NDP’s appeal and shift the spotlight away from the pro-Bumiputera policies toward various ethnic settlements. Eventually, the Chinese community warmly received the NDP, an outcome attributed to the program’s commitment to growth and deregulation and its accommodation of cultural and educational interests (Heng 1997). Public demonstration of broad engagement, and Vision 2020’s inclusive Bangsa Malaysia aspiration, evidently facilitated buy-in across various communities (Osman-Rani 1992).

Third, political interests prevailed on the policy. Demands for the NEP’s extension resounded at the 1989 UMNO General Assembly; the NECC felt the pressure.14) This point must be qualified; absence of such influence would not necessarily have conceived a post-1990 plan that dismantled the NEP’s second prong. While politics perpetuated the fixation with ethnic quotas, the NECC’s debates on NEP continuity focused substantially on equity measurement issues rather than Bumiputera development more broadly (Lim 2014).15) The singular figure of Mahathir, of course, also loomed large, for his public utterances that ethnic quotas would be maintained (Means 1990) and his prized BCIC.16) Indeed, the NDP’s growth with equity thrust, with privatization as the vehicle for the BCIC, accommodated his agenda. Rapid economic growth and private higher education expanded socioeconomic opportunities, especially for non-Bumiputeras, but Bumiputera preferential policies remained firmly rooted, and even expanded.

Nonetheless, a misconception that redistributive policies diminished after 1990 pervaded across the political divide. This view served both sides; it allowed the government to deflect attention from contentious ethnic policies, while fuelling an oppositional stance that the NEP ended in 1990 and therefore its perpetuation constituted a broken promise. All parties failed to recognize the embeddedness of Bumiputera affirmative action regardless of the NEP or NDP umbrella, and omitted cogent analyses of policy outcomes and alternatives.

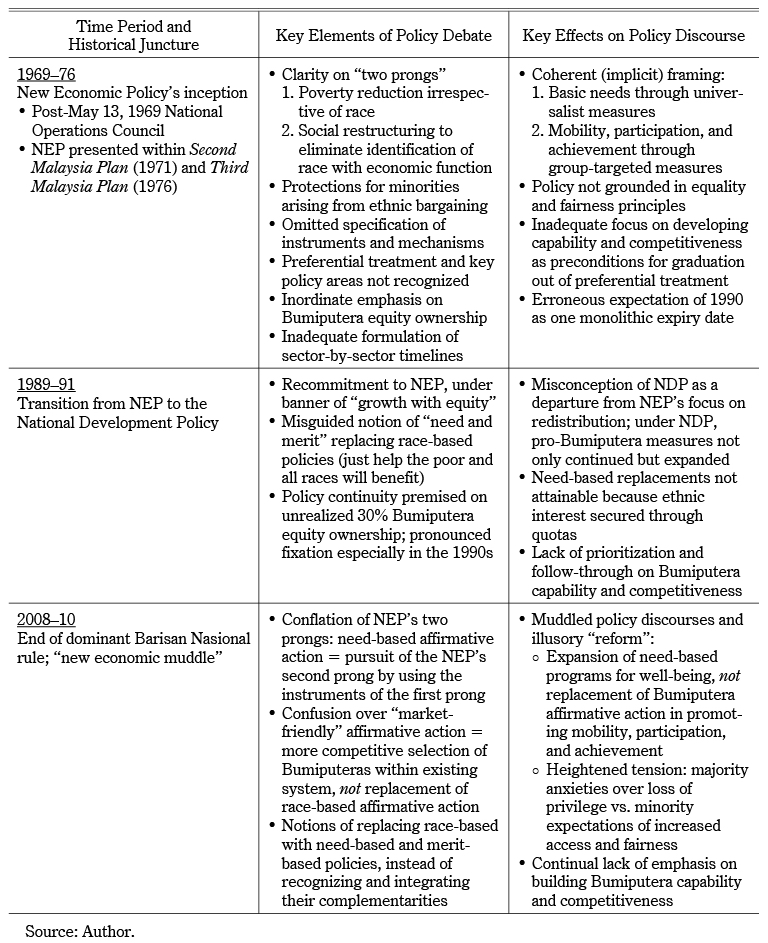

It may be helpful to recap the first two historical junctures before launching into a discussion of the third. Table 1 presents key information on the three historical junctures.

Table 1 Malaysia’s New Economic Policy: Summary of Three Historical Junctures

“New Economic Muddle”: Systemic Incoherence, Selective Interventions

The 1990s further reshaped discourses. Affirmative action burgeoned behind the scenes, but rapid wealth accumulation, and the ascendancy of a Bumiputera corporate elite considerably marred by profiteering, patronage, and rent-seeking, garnered the most attention (Lee 2017). General growth in income and opportunity, especially in newly approved private higher education institutions, provided a vent for pent-up frustrations, perhaps precluding critical scrutiny of those policy sectors. However, the NEP became conflated with privatization, which was arguably the most momentous project of the 1990s and driver of the above-mentioned unsavory outcomes, but only one part of a vast pro-Bumiputera system. Indeed, the outreach of affirmative action in higher education, employment, SME development, and microfinance to ordinary Bumiputera households greatly exceeded that of privatization, which benefited the top sliver.

Political watersheds preceded the next pivotal policy, the New Economic Model, launched in 2010. The 2008 general election saw the fifty-year ruling Barisan Nasional (formerly the Alliance Party) lose its two-thirds of parliament seats and govern without a formidable majority. That electoral outcome, a failure by BN’s standards, triggered a prime ministership handover from Abdullah Badawi to Najib Razak, who set out an inclusive platform to lure back disaffected non-Malays. Pakatan Rakyat, an unprecedentedly strong federal opposition, had also attempted to rewrite the NEP, by projecting “need-based affirmative action” as a replacement for BN’s race-based affirmative action, prior to the release of the NEM.17)

A curious bipartisanship emerged. The NEM, under BN’s aegis, trumpeted the same bold promise—but it collapsed under the combined weight of its own incoherencies and the subsequent political backlash. The NEM’s muddled and gap-riddled treatment of affirmative action is encapsulated in its summation of the subject:

Affirmative action programmes and institutions will continue in the NEM but, in line with the views of the main stakeholders, will be revamped to remove the rent-seeking and market distorting features which have blemished the effectiveness of the programme. Affirmative action will consider all ethnic groups fairly and equally as long as they are in the low income 40% of households. Affirmative action programmes would be based on market-friendly and market-based criteria together taking into consideration the needs and merits of the applicants. An Equal Opportunities Commission will be established to ensure fairness and address undue discrimination when occasional abuses by dominant groups are encountered. (Malaysia, NEAC 2010, 61)18)

The flaws derived, firstly, from unexamined bias and hasty generalization. The impetus for revamping affirmative action hinged exclusively on the problems of rent-seeking and market distortion, which are serious problems but pertinent predominantly to public procurement and wealth distribution programs, and emphatically do not represent the totality of affirmative action. The NEM superimposed the most acute problems of affirmative action onto the entire system and showed no cognizance of the reality that rent-seeking and market distortion would factor in differently, if at all, in the affirmative action programs of greater scope and outreach, especially in higher education, microfinance, mass savings schemes, and public sector employment. The NEM document made no mention of the vast range of pro-Bumiputera measures—including MARA, PUNB, Tekun, matriculation colleges, Asasi pre-university foundation courses, Permodalan Nasional Berhad (National Equity Limited), public procurement, government-linked companies (GLCs), SME loans through SME Corp, and public sector employment (Malaysia, NEAC 2010).

Moreover, the NEM made sweeping claims about switching from race to need and merit, akin to the inchoate merit and need suggestions of the 1980s that failed to provide policy specifics beyond anodyne and vapid declarations. The NEM mainstreamed the lowest income bracket, termed the bottom 40 percent of households (B40), as a target group but failed to realize that low-income targeting predominantly applied to basic needs provision and had limited relevance to the pro-Bumiputera system. In essence, the question was whether pro-poor or pro-B40 preference could replace pro-Bumiputera preference. To some extent, opportunity could be allocated preferentially on the basis of B40 socioeconomic status, instead of Bumiputera identity, in higher education admissions and scholarships and microfinance, but much less so, if at all, in the other affirmative action policy sectors of employment, business, and wealth ownership. In the awarding of government contracts or SME loans to Bumiputera firms, not only must capability and potential take precedence, but giving preference to poorer—and possibly less competent—operators may be downright hazardous, e.g., in public works. The NEM’s proposal to establish an Equal Opportunities Commission even appended the bizarre qualification that the institution would address “occasional abuses by dominant groups,” rather than framing the problem more prudently as a matter of principle and conduct regardless of frequency or perpetrator.

The NEM’s grandiose yet opaque pronouncements allowed it to be appropriated in the service of opposing interests. Clearly, its propositions for “market-friendly” and “market-based” reforms entailed selecting more capable and less corrupt Bumiputeras over less capable and more corrupt Bumiputeras, not an abolition—nor even substantial downsizing—of the Bumiputera preferential system. Unfortunately, the cryptic presentation of a policy “revamp” triggered polarized, and mutually amplifying, reactions (Gomez 2015). On one side, the NEM confirmed desires for affirmative action to be dismantled, exhibited in the resounding welcome it received from some segments. At the opposite end, the NEM’s deficits in clarity and temperance allowed misinterpretations to be taken as a threat to Malay privileges, and for sentiments to be inflamed. The Najib administration conceded to a ferocious anti-NEM groundswell from segments of the Malay community, effectively rallied under the banner of the newly formed NGO Perkasa (Segawa 2013). Not only was the NEM effectively retracted, but Najib also promulgated Bumiputera Economic Empowerment, subsequently renamed the Bumiputera Economic Transformation Programme (BETR), from 2012 with an emphasis on creating dynamic Bumiputera SMEs and corporations and reaching out to the Bumiputera B40.

Again, it is imperative to differentiate political dynamics from policy contents. While the political milieu induced Najib to launch the BETR with fanfare and aggrandizement, there is every likelihood that such interventions would have emerged under a different label—even if the anti-NEM backlash had not transpired. We must recall that the NEM did not commit to eliminating Bumiputera programs but committed to continue promoting competitive Bumiputera enterprise while avoiding past proclivities toward rent-seeking and corruption. The BETR, rebranded again in 2015 as the Bumiputera Economic Community, mainly experimented with new modes of promoting Bumiputera enterprise—and in a selective and targeted manner, while omitting attention to the vast regime of Bumiputera preferential programs, many of which were arguably underperforming (Lee 2017). The BETR and Bumiputera Economic Community thus introduced some novel measures but also overstated their scope and impact.19) However, popular and political discourses remained polarized, with the government typically overselling the BETR, and critics dismissing it preemptively without attempting to unpack its contents (Kua 2018). Academic literature has largely neglected the subject.

Developments preceding the NEM illustrate the propensity for declarations of affirmative action reform to become overblown in the public mindset. Liberalization of Bumiputera equity allocations in various service sectors was announced in 2009, and it received a resounding welcome. Concurrently, the government established the private equity institution Ekuinas to promote Bumiputera ownership and fill the gap emerging from the rollback of ethnic equity requirements. Ekuinas as a follow-up package escaped notice, yet it patently demonstrated the systemic endurance of pro-Bumiputera policies. It was difficult, but also highly necessary, to enhance capacity building and modify overt ethnic quotas in programs with extensive outreach, especially in higher education, public procurement, and micro/small business support (Lee 2014). Unsurprisingly, the NEM did not attempt to effect change in these areas.

Thus, Malaysia’s affirmative action policy discourses continue to be mired in stasis and polarization—despite putative reform agendas, and in some ways precisely because of such rhetoric. Three reasons for this bedraggled state of policy discourse can be posited. First, the prevailing views of affirmative action reform continually lacked a systematic formulation, especially by conflating the NEP’s judicious two-pronged distinction between essentially need-based poverty alleviation and ethnicity-conscious social restructuring. Rather than calling for the second prong to be abolished, a more logical if politically controversial argument more prominent in the past, in recent times the argument follows along the lines that the NEP’s second prong should be pursued by using the instruments of the first prong. The appearance of an ostensibly bold reform agenda succumbing to political pressure has caused most to overlook the manifest flaws in the NEM’s conception of affirmative action—and the fact that all along it called for modification, not overhaul. Academic literature has also erroneously conceptualized universalist and targeted interventions as substitutes, without considering that the problems being solved—and hence the instruments required—are fundamentally different, albeit complementary (Gomez 2012; Gomez et al. 2013).

The notion of need-based affirmative action as an all-encompassing replacement for race-based affirmative action has become entrenched—more vocally as an opposition platform, but also in the form of broadly conceived pro-B40 policies. As the argument goes, need-based affirmative action will ultimately benefit Bumiputeras to a greater extent, since they comprise a disproportionately higher share of the poor and disadvantaged. However, need-based policies address fundamentally different problems, revolving mainly around basic needs, rights, and entitlements, not the questions of access, participation, and capability that predominantly occupy the realm of affirmative action. A national consensus on social assistance—sealed by the expansion of welfare programs for the poor irrespective of race under Pakatan-governed states since 2008 and the federal government under BN, then Pakatan, then Perikatan Nasional—has, perhaps unwittingly, precluded rigorous attention to the vast, embedded system of Bumiputera preferential programs.

Another popular position paints the NEP as the epitome of BN race-based policy failure and marries it with the UMNO-dominant coalition’s race-based politics, which induces another tightly held conflation—that eliminating race-based politics readily expunges race-based policies. The logical holes and political limits of this mindset were strikingly demonstrated by the inability of Pakatan Rakyat to meaningfully replace race-based policies with its professed need-based affirmative action throughout a decade-plus rule in state governments (2008–present), and by Pakatan Harapan’s (PH) advocacy of pro-Bumiputera policies in its 2018 general election campaign (Lee 2018).20) The PH federal administration struggled to maintain policy coherence, primarily reacting to electoral sentiment by retaining pro-Bumiputera affirmative action with token offerings to minorities, but raising minority expectations of reform that were much more complicated than it envisaged.21) Having lost power in 2020, PH has reverted to its rallying cry of need-based affirmative action.22)

Second, the prevalence of policy sloganeering over substantive analysis stems from deficient empirical rigor and propensities on all sides toward selective and preconceived positions. Empirical analysis of Malaysia’s affirmative action requires breadth in accordance with the vastness of the system. However, official sources recycle threadbare truisms about NEP successes and shortfalls, epitomized in the Shared Prosperity Vision 2030, which gave unqualified endorsement to all spheres except equity ownership:

The NEP has restored confidence and understanding among ethnic groups and created various opportunities for economic participation. Among the successes of the NEP are reducing hardcore poverty, increasing household income, restructuring of society and reducing ethnic group identification based on economic activities and enhancing political stability. Nonetheless, the target of at least 30% Bumiputera equity ownership has not been met. (Malaysia, Ministry of Economic Affairs 2019, 4-01)

The NEP’s lack of attention to policy design and mechanisms, and to transition paths away from overt quotas and preferences, persists—but unlike 1971, when such foresight may have been beyond reach, by the 2010s hindsight should have sufficed to engage in rigorous policy debates. Engrossed in its appealing but ultimately misplaced promotion of a “market-friendly” and pro-poor alternative agenda, the NEM mostly sidestepped the challenging and contentious aspects of the NEP but was spiritedly embraced by an urban, multiethnic populace and segments of civil society,23) as well as the media, especially English-language publications both local and international (Economist, May 18, 2017).24) These notions of reform clearly represent popular yearnings, although the expectations projected onto the NEP differ. Some may expect greater access to public higher education, others more opportunity for government contracts and enterprise funding, and for some it boils down to a general aversion to ethnically framed policies.

Indeed, mainstream criticisms are prone to blinkers of their own. The dominant NEP critique continually cleaves to a narrow appraisal that affirmative action overwhelmingly benefits Malay elites in a manner exacerbated by rent-seeking and corruption (Gomez 2012). This argument often appends an assertion that intra-ethnic inequalities have been rising as a result of affirmative action. The argument that there was runaway wealth accumulation at the top, spurred by privatization and liberalization, persuasively applied to the 1990s. Calculations of the Gini coefficient of inequality, based on the nationally representative household income surveys, documented rising inequality in the decade prior to the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The data also showed that inequality was highest within the Bumiputera population, prompting arguments that inequality within ethnic groups should be given more priority than inequality between ethnic groups (Ishak 2000; Ragayah 2008). In the post-Asian financial crisis era, income inequality levels fluctuated, then markedly declined from 2004 to 2019, such that in 2019 the level of inequality within the Bumiputera population was the lowest among the three main ethnic categories (Lee and Choong 2021). The widely held assumption that inequality has been rising, and is most severe in the Bumiputera population, is empirically refuted by the most authoritative evidence.25)

The relationship between income inequality and affirmative action is complex. The post-Asian financial crisis context, which saw the collapse of privatization and reconfiguration of privatized entities as GLCs, is significantly removed from the plutocratic Bumiputera wealth accumulation of the 1990s. Over the past two decades, some interventions disproportionately benefiting high-income households, such as GLC top appointments, have caused inequality to rise; other interventions that have grown the middle and lower middle classes—especially mass higher education and declining earnings premiums on higher education qualifications, recruitment in government and GLCs, and small business support—have caused inequality to fall. On balance, the drop in intra-Bumiputera inequality signals that inequality-reducing trends have been outweighing inequality-increasing trends.

However, in seeking to explain the resistance to affirmative action reform, much of the literature inordinately emphasizes the vested interests of politically linked elites in retaining the system (Chin 2009; Gomez 2012) or simplistically reduces the problem to a lack of reformist political will (Gomez et al. 2021). This thinking neglects the expansive and embedded network of affirmative action and the socioeconomic access it affords to the Bumiputera middle and lower classes—and the specific ways this complicates efforts to change the system. Nationally representative opinion polls show solid support on the Malay ground for policies granting Malays special access, and also widespread unease among other groups (Merdeka Center 2010; Al Ramiah et al. 2017).26) An alternate and more systematic analysis accounts for these social currents and identifies the decisive shortcoming of the system: while vastly extending socioeconomic access to Bumiputeras on a preferential basis, these numerous programs have fallen short in empowering the beneficiaries. Ultimately, Malaysia is unable to move on from the NEP’s second prong not because the system benefits only the elite, as widely argued, although upwardly skewed distribution is an important problem that affects some parts of the system. Rather, the primary reason pro-Bumiputera policies endure is because the system vastly provides opportunities but inadequately utilizes those opportunities to develop Bumiputera capability and competitiveness. The combination of extensive access and insufficient empowerment contributes to the pervasive sense among Malays that special assistance remains necessary and that the community remains under-equipped for open competition.

Third, as in the previous historical junctures, political rhetoric to maintain Bumiputera privileges still reverberates, but there are nuances to appreciate. Unlike overt pressure from the erstwhile hegemonic UMNO, which secured massive expansions of pro-Bumiputera policies in 1971 and 1990, BN’s initial tone in presenting the NEM in 2010 was more inclusive, and the subsequent promulgation of Bumiputera transformation paled in magnitude to the previous two episodes. In part, accommodations of minority groups have also rolled out, whether through the introduction of 10 percent allocations to non-Bumiputeras in previously exclusive Bumiputera programs in 2001–2, reduction in Bumiputera equity requirements in 2009, or introduction of special interventions for Indian or Orang Asli communities in the mid-2010s. Popular demands for welfare programs have also heightened government efforts to groom performative legitimacy by continually implementing these basic needs and pro-B40 measures, and reiterating the “regardless of race” nature of such outreach. These are small marks of progress, although in the grand scheme of things Malaysia continues to evade a direct, critical, and systematic reckoning with affirmative action (Malaysia 2021).

All sides, whether championing Bumiputera transformation or need-based affirmative action as a replacement for race-based affirmative action, opt for convenient answers and often oversell their positions. The political will to maintain the system undeniably endures, but politics also contribute to a rudderless drift in policy discourses.

The New Economic Policy beyond Fifty

The NEP’s arrival at its fifty-year milestone marks an opportune moment for retrospection and introspection. The NEP remains insinuated throughout the Malaysian collective consciousness and is invoked in public discourses—often in ambiguous, prejudiced, and even revisionist terms. After three momentous junctures in its fifty-year history, the NEP still lacks closure. In line with the three-angled structure of this paper, we conclude with some thoughts on how Malaysia can move forward systematically and constructively—in terms of policy conception, policy design, and mechanisms—and on the politico-economic prospects for change. This framework applies primarily to the pursuit of inclusiveness; Malaysia’s economic growth and sustainable development strategies require independent policy formulation—with integration of overlaps.

Conceptually, a good place to start is by re-appreciating the NEP’s strengths, especially its principal basis for distinguishing the two prongs. This dual framework can be broadened systematically, with a focus on equality and basic needs for all—irrespective of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and other forms of identity—rather than the NEP’s specifications of poverty reduction as the outcome and race as the only targeted population category. The principles of fairness and diversity constitute the second pillar; this corollary to social restructuring also broadens the perspective from racial imbalance to equitable representation, participation, and capability development in relevant socioeconomic spheres. Rather than carving out domains where Bumiputera quotas apply versus domains where they do not, the interplay of group preference and need-based preferences should be applied in a comprehensive manner. The Malaysian government should find specific ways to incorporate need-based selection, especially in higher education—some of which are already in place, on an ad hoc basis—as well as microfinance, and ways to more rigorously provide opportunity to Bumiputeras and disadvantaged groups based on merit and competition, integrated with plans for graduating out of preferential treatment.

In policy design and empirical evaluation, the repeated inability of quantitative targets and deadlines to deliver breakthroughs in reform signals the need to focus more on process and qualitative outcomes, by clearly identifying programs that involve group preferential treatment and focusing on capability development as preconditions that facilitate future reform. Empirical analysis must follow up by focusing on outcomes that are more pertinent to capability development, such as student achievement and graduate employability (Lee 2012), and the share of micro, small, and medium enterprises. Rather than one monolithic target or deadline for the entire system to be dismantled, various programs should run their own course, with customized targets and timelines (Lee 2021a).

The politics surrounding affirmative action remain fraught with polarized positions but also stultified by the pervasive discourses of reform. Majority and minority group interests remain adversarial, but in new and arguably less pronounced ways. A different approach that might help break out of the gridlock starts by considering the dynamics of change. Essentially, the common calls for affirmative action to be abolished boiled down to one of two premises: first, guilt over excluding minorities from certain opportunities; and second, regret over maintaining a failed project that should have been abandoned (Chin 2009). A possible third path could be charted, anchored in an acknowledgement that the majority Bumiputeras must be sufficiently empowered with capability and competitiveness in order to undertake systematic reform. Attention then focuses on a building-up process, while simultaneously finding ways to integrate more need-based assistance and merit-based selection, and other mechanisms besides quotas for promoting equitable representation. The process also calls for minority and majority groups to collectively pursue equality and fairness, but also to rethink the familiar dispositions and look beyond communal interests. Minority groups will need to shift from grievance-centric stances to advocacy of more effective Bumiputera capability development; the majority must acknowledge the preferential mechanisms through which they receive benefits and the imperative of graduating out of receiving special treatment. New avenues of engagement require a level of trust and candor that remains insufficient. However, given that a target-hitting and expiry date approach has not broken Malaysia out of the persisting policy impasse, an approach based on trust building and continuous engagement might be the basic reset that the country needs.

Accepted: February 3, 2022

Acknowledgments

This paper benefited from excellent research assistance by Winston Wee and Kevin Zhang and insights of the eminent individuals who were interviewed, along with helpful comments and critiques from Khoo Boo Teik, Shankaran Nambiar, Greg Lopez, and two anonymous referees. The author gratefully acknowledges their contributions but implicates none of them for the contents of this paper.

References

Al Ramiah, Ananthi; Hewstone, Miles; and Wölfer, Ralf. 2017. Attitudes and Ethnoreligious Integration: Meeting the Challenge and Maximizing the Promise of Multicultural Malaysia. Final Report: Survey and Recommendations Presented to the Board of Trustees, CIMB Foundation, Kuala Lumpur.↩ ↩

Chee Peng Lim. 1976. Towards a Centrally Planned Economy? Guardian, October/November, p. 2.↩

Chin, James. 2009. The Malaysian Chinese Dilemma: The Never Ending Policy (NEP). Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 3: 167–182.↩ ↩

Chin Yee-Whah; and Teh, Benny Cheng Guan. 2017. Malaysia’s Protracted Affirmative Action Policy and the Evolution of the Bumiputera Commercial and Industrial Community. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 32(2): 336–373.↩

DNU. 1970. The New Economic Policy. Policy statement issued as a Directive to Government Departments and Agencies. Reproduced as Document C in Growth and Ethnic Inequality: Malaysia’s New Economic Policy, by Just Faaland, Jack R. Parkinson, and Rais Saniman, pp. 305–318 (London: Hurst, 1990).↩

Daim Zainuddin. 2019. MySay: A New Economic Policy for a New Malaysia. Edge Weekly. August 13. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/mysay-new-economic-policy-new-malaysia, accessed May 27, 2021.↩

Faaland, Just. 1969a. Policies for Growth with Racial Balance. Internal government paper. Reproduced as Document A in Growth and Ethnic Inequality: Malaysia’s New Economic Policy, by Just Faaland, Jack R. Parkinson, and Rais Saniman, pp. 245–270 (London: Hurst, 1990).↩ ↩

―. 1969b. Racial Disparity and Economic Development. Internal government paper. Reproduced as Document B in Growth and Ethnic Inequality: Malaysia’s New Economic Policy, by Just Faaland, Jack R. Parkinson, and Rais Saniman, pp. 271–304 (London: Hurst, 1990).↩ ↩

Faaland, Just; Parkinson, Jack R.; and Saniman, Rais. 1990. Growth and Ethnic Inequality: Malaysia’s New Economic Policy. London: Hurst.↩ ↩

Gerakan. 1984. The National Economic Policy: 1990 and Beyond. Penang: Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia (Gerakan).↩ ↩ ↩

Gerakan Rakyat. 1976. The Role of the Private Sector in the Third Malaysia Plan. Gerakan Rakyat 2(1) (October 9).↩ ↩

Gomez, Edmund Terence. 2015. The 11th Malaysia Plan: Covertly Persisting with Market-Friendly Affirmative Action? Round Table 104(4): 511–513. doi: 10.1080/00358533.2015.1063844.↩

―. 2012. Targeting Horizontal Inequalities: Ethnicity, Equity, and Entrepreneurship in Malaysia. Asian Economic Papers 11(2): 31–57. doi: 10.1162/ASEP_a_00140.↩ ↩ ↩

Gomez, Edmund Terence; Cheong Kee-Cheok; and Wong Chan-Yuan. 2021. Regime Changes, State-Business Ties and Remaining in the Middle-Income Trap: The Case of Malaysia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 51(5): 782-802. doi: 10.1080/00472336.2021.1933138.↩

Gomez, Edmund Terence; Saravanamuttu, Johan; and Mohamad, Maznah. 2013. Malaysia’s New Economic Policy: Resolving Horizontal Inequalities, Creating Inequities? In The New Economic Policy in Malaysia: Affirmative Action, Ethnic Inequalities and Social Justice, edited by Edmund Terence Gomez and Johan Saravanamuttu, pp. 317–334. Singapore and Petaling Jaya: NUS Press, ISEAS, and SIRD.↩

Heng Pek Koon. 1997. The New Economic Policy and the Chinese Community in Peninsular Malaysia. Developing Economies 35(3): 262–292. https://www.ide.go.jp/library/English/Publish/Periodicals/De/pdf/97_03_03.pdf, accessed February 21, 2021.↩ ↩ ↩

Ho Khai Leong. 1992. Dynamics of Policy-Making in Malaysia: The Formulation of the New Economic Policy and the National Development Policy. Asian Journal of Public Administration 14(2): 204–227. doi: 10.1080/02598272.1992.10800269.↩

Ishak Shari. 2000. Economic Growth and Income Inequality in Malaysia, 1971–95. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 5(1/2): 112–124. doi: 10.1080/13547860008540786.↩

Jomo K. S. 1994. U-Turn? Malaysian Economic Development Policies after 1990. Townsville: James Cook University of North Queensland.↩ ↩

Kamal Salih. 2019. Leadership Style. In Driving Development: Revisiting Razak’s Role in Malaysia’s Economic Progress, edited by Rajah Rasiah and Kamal Salih, pp. 13–28. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press.↩

Kamal Salih; and Zainal Aznam Yusof. 1989. Overview of the NEP and Framework for a Post-1990 Economic Policy. Malaysian Management Review 24: 13–61.↩

Kathirasen, A. 2019. A Rare Glimpse into NEP’s Origins. Free Malaysia Today. July 16. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/opinion/2019/07/16/a-rare-glimpse-into-neps-origins/, accessed June 28, 2022.↩

Kow Gah Chie; and Lee, Annabelle. 2019. Anwar Wants to Speed Up Needs-Based Affirmative Action. Malaysiakini. July 26. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/485528, accessed May 5, 2021.↩

Kua Kia Soong. 2018. Never-ending Bumi Policy Dashes Hope for “New Malaysia.” Malaysiakini. December 31. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/458326, accessed May 25, 2021.↩

Lee Hwok Aun. 2021a. Affirmative Action in Malaysia and South Africa: Preference for Parity. London and New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315114071.↩ ↩

―. 2021b. Malaysia’s New Economic Policy and the 30% Bumiputera Equity Target: Time for a Revisit and a Reset. ISEAS Perspective 2021 No. 36. Singapore: ISEAS.↩

―. 2018. New Regimes, Old Policies and a Bumiputera Reboot. New Mandala, September 16.↩

―. 2017. Malaysia’s Bumiputera Preferential Regime and Transformation Agenda: Modified Programmes, Unchanged System. Trends in Southeast Asia 2017 No. 22. Singapore: ISEAS.↩ ↩

―. 2014. Affirmative Action: Hefty Measures, Mixed Outcomes, Muddled Thinking. In Routledge Handbook on Contemporary Malaysia, edited by Meredith Weiss, pp. 162–176. New York: Routledge.↩

―. 2012. Affirmative Action in Malaysia: Education and Employment Outcomes since the 1990s. Journal of Contemporary Asia 42(2): 230–254. doi: 10.1080/09500782.2012.668350.↩

Lee Hwok Aun; and Choong, Christopher. 2021. Inequality and Exclusion in Malaysia: Macro Trends, Labour Market Dynamics and Gender Dimensions. In Inequality and Exclusion in Southeast Asia: Old Fractures, New Frontiers, edited by Lee Hwok Aun and Christopher Choong, pp. 87–132. Singapore: ISEAS.↩ ↩

Lee San Choon. 1976. New Frontiers of the MCA: Presidential Address to the 24th General Assembly. Guardian. September.↩

Leong, William. 2019. “Shared Prosperity” Requires a “Shared Malaysia.” Malaysiakini. October 17. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/496224, accessed May 5, 2021.↩

Lim Guan Eng. 2021. DAP Is Disappointed at Former Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s Narrative. Press statement, April 17. https://dapmalaysia.org/Kenyataan-Akhbar/2021/04/17/32111/, accessed May 17, 2021.↩

―. 2007. Non-Malays Are Not Angry with the NEP for Helping the Malay Poor, Malays Are Not Angry with the NEP for Helping the Non-Malay Poor, but Malaysians Are Angry with the NEP for Being Used as a Tool of Crony Capitalism to Enrich the Wealthy. Press statement, July 11. https://dapmalaysia.org/english/2007/july07/lge/lge679.htm, accessed May 17, 2021.↩

Lim Lin Lean. 1988. The Erosion of the Chinese Economic Position. In The Future of Malaysian Chinese, pp. 37–55. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Chinese Association.↩

Lim Teck Ghee. 2014. Abdullah Badawi, the NECC and the Corporate Equity Issue: A Little Known Connection. In Awakening: The Abdullah Badawi Years in Malaysia, edited by Bridget Welsh and James Chin, pp. 457–480. Petaling Jaya: SIRD.↩

Ling Liong Sik. 1995. The Malaysian Chinese: Towards Vision 2020. Petaling Jaya: Pelanduk.↩

Mahathir Mohamad. 1991. Malaysia: The Way Forward. Paper presented to the Malaysian Business Council, February 28.↩ ↩

Malaysia. 2021. The Twelfth Malaysia Plan, 2021–25. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩

―. 2018. Mid-term Review of the Eleventh Malaysia Plan. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩

―. 1991. The Sixth Malaysia Plan, 1991–1995. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩ ↩ ↩

―. 1989. Mid-term Review of the Fifth Malaysia Plan, 1986–90. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩ ↩ ↩

―. 1986. The Fifth Malaysia Plan, 1986–90. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩

―. 1976. The Third Malaysia Plan, 1976–80. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

―. 1973. Mid-term Review of the Second Malaysia Plan, 1971–75. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩

―. 1971. The Second Malaysia Plan, 1971–75. Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Malaysia, Ministry of Economic Affairs. 2019. Shared Prosperity Vision 2030. Putrajaya: Ministry of Economic Affairs.↩

Malaysia, National Economic Advisory Council (NEAC). 2010. New Economic Model for Malaysia, Part 1. Putrajaya: NEAC.↩ ↩ ↩

Malaysia, National Economic Consultative Council (NECC). 1991. Dasar Ekonomi untuk Pembangunan Negara (DEPAN): Laporan Majlis Perundingan Ekonomi Negara [National Economic Development Policy: Report of the National Economic Consultative Council]. Kuala Lumpur: NECC.↩ ↩ ↩

Means, Gordon. 1990. Malaysia in 1989: Forging a Plan for the Future. In Southeast Asian Affairs 1990, edited by Ng Chee Yuen and Chandran Jeshurun, pp. 183–203. Singapore: ISEAS.↩ ↩ ↩

Merdeka Center. 2019. National Public Opinion Survey: Perception towards Economy, Leadership and Current Issues. Bangi: Merdeka Center for Opinion Research.↩

―. 2010. Malaysian Political Values Survey. Bangi: Merdeka Center for Opinion Research.↩ ↩

Milne, R. S. 1976. The Politics of Malaysia’s New Economic Policy. Pacific Affairs 49(2): 235–262. doi: 10.2307/2756067.↩ ↩

Nik Nazmi Nik Ahmad. 2019. The Need for Needs-Based Affirmative Action. Malaysiakini. August 6. https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/486855, accessed May 5, 2021.↩

Osman-Rani H. 1992. Towards a Fully Developed Malaysia: Vision and Challenges. In Southeast Asian Affairs 1992, edited by Daljit Singh, pp. 202–217. Singapore: ISEAS. doi: 10.1355/9789812306821-014.↩

―. 1990. Malaysia’s New Economic Policy: After 1990. In Southeast Asian Affairs 1990, edited by Ng Chee Yuen and Chandran Jeshurun, pp. 204–226. Singapore: ISEAS.↩ ↩