Contents>> Vol. 12, No. 1

Creation of the State Forest System and Its Hostility to Local People in Colonial Java, Indonesia

Mizuno Kosuke,* Hayati Sari Hasibuan,** Okamoto Masaaki,*** and Farha Widya Asrofani†

*水野広祐, School of Environmental Science, University of Indonesia, Gedung Sekolah Ilmu Lingkungan, Jl. Salemba Raya 4, Jakarta, 10430, Indonesia; Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

Corresponding author’s e-mail: mizuno.kousuke.22e[at]st.kyoto-u.ac.jp

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7411-8074

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7411-8074

**School of Environmental Science, University of Indonesia

e-mail: hayati.hasibuan[at]ui.ac.id

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5728-2120

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5728-2120

***岡本正明, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

e-mail: okamoto[at]cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8939-4170

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8939-4170

†School of Environmental Science, University of Indonesia

e-mail: farhawidya13[at]gmail.com

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7205-0440

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7205-0440

DOI: 10.20495/seas.12.1_47

Indonesia has a vast area of state forests (kawasan hutan) covering 65 percent of the country’s land surface. State forests provide timber and enable the protection and conservation of forests. They also provide a living environment for local people, which comes with many problems, including overlapping land rights, illegal logging, and serious environmental degradation. This study looks into the origin of the state forest system during the colonial era, paying particular attention to the establishment of the Forest Service. Faced with deforestation at the end of the eighteenth century and the middle of the nineteenth, a forest administration system was established in the name of forest protection and conservation, to implement a bureaucratic system of administration based on wage labor. Finally, the Forest Service was set up. The Forest Service supplied timber for the government’s infrastructure development, such as state railway construction, and supplied timber and firewood for local people. The Forest Service’s revenue covered its expenditure and even created a budget surplus that contributed to state revenue. The system was quite unsympathetic to local people—for example, slash-and-burn practices were prohibited, and defiant locals were punished—and the government never attempted to involve local people in the implementation of the forest conservation program. The government attempted to stabilize the system in part by issuing permits allowing certain activities. However, the permit system barely functioned, and almost nobody tried to get permits. The number of forest offenses such as stealing trees increased until the end of the 1930s. The fundamental problem was that local people regarded their use of the forest—such as for cutting trees and gathering fallen trees, leaves, and branches—as their customary right; the colonial government, on the other hand, denied them this right, confining it within the permit and police system.

Keywords: state forest, Forest Service, forest police, forest offenses, customary rights

Introduction

In developing countries, conditions pertaining to forest tenure tend to be contested, overlapping, and insecure (White and Martin 2002; RRI 2008; Sunderlin et al. 2008). These challenging conditions are aftereffects of the state appropriation of forests centuries ago (RRI 2012), which led to a loss of local control over forest use and management decisions (Ellsworth and White 2004; Sunderlin et al. 2014).

Indonesia is no exception to this general trend in many developing countries. Around 65 percent of Indonesia’s land surface is government-designated forest area (kawasan hutan), and forty million people live within it. Many of them cannot secure their land rights, and the overlapping of land rights is a constant source of land conflicts (Fauzi 2017). The domination and expansion of the plantation and timber industry continue, and the customary rights of local people are ignored (Ismatul et al. 2018). A recent study of peatland fires and degradation shows that the issue has reached such a pass partly because the majority of peatlands in Indonesia are located within the state forests and these are too vast for the state to manage (Mizuno et al. 2021).

Agrarian reform began after President Soeharto stepped down, and it was officially approved by the People’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat) in 2001. The government also initiated its own agrarian reform program called Tanah Objek Reforma Agraria (Agrarian Reform Targeted Land). Despite these efforts, the agrarian issues that trouble state forests remain largely unresolved (Endriatmo and Eko 2018, 3–16), although the Constitutional Supreme Court (Mahkamah Konstitusi) did hand down a judgment recognizing the legal basis of customary law in the state forests (Fauzi 2018). In 2019 the government issued a new regulation placing customary forest (hutan adat) and private forest (hutan hak) on the same level as state forest, and stating that those statuses would be granted based on applications submitted by customary communities and private bodies and ratified by the government. However, only a small number of cases have been settled judicially so far.1)

The official establishment of state forests and the issue of land rights within their boundaries commenced during the colonial era. Forest issues, especially in the context of the founding of the Forest Service and the system’s legal basis, have been widely studied. Research projects on the historical evolution of forestry include teak forests in Java by Nancy Lee Peluso (1992) and Indonesia by Peter Boomgaard (2005), with particular emphasis on forests and forestry policy in Indonesia undertaken by the Departemen Kehutanan (1986a; 1986b). These studies discuss the formation of the Forest Service (het Boschwezen) system from various viewpoints. Peluso and Peter Vandergeest also conducted studies on the development of forestry education in Southeast Asia (Vandergeest and Peluso 2006a; 2006b) and carried out a comparative study on the development of land and forestry policies in Java, Indonesian Borneo, Thailand, and Malaysia. The Indonesian Forest Service was shown to be superior in its number of staff members (Peluso and Vandergeest 2001). There has also been abundant research on the causes of forest loss, including investigations into forest conversion into agricultural land for oil palm cultivation (Cramb and McCarthy 2016), illegal logging (Dudley 2002), smuggling (Obidzinski et al. 2007), and forest fires (Applegate et al. 2002). John McCarthy highlighted illegal logging as well as illegal mining as persistent problems in Indonesia. He discussed the governance point of view, showing the necessity of combining localized modes of participation and accountability with the capacity of a central state to carry out the required degree of monitoring, supervision, and sanctioning to counteract the power of unaccountable local elites (McCarthy 2011).

While these studies on the history of forestry in Indonesia are valuable, none of them presents a clear idea of the state of forest land-tenure issues. In contrast, Eko Cahyono et al. (2018) discuss studies of contemporary issues in state forests from the land rights perspective, examining land conflicts and relationships to customary laws, but there is scant mention of the colonial-era system. They also miss a discussion of historical development looking at the formation of the system, colonial-era relations with local populations, and the origins of current issues.

This study focuses on the formation of state forests and the origins of problems from the eighteenth century until today, paying considerable attention to the legal basis of state forest in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This study pays attention to the role of the state forest and Forest Service in economic infrastructure by supplying timber for railways, dikes, or firewood and by supplying revenue to fund the Forest Service and contribute to the state budget. Previous studies have also been consulted, allowing for a wider picture of the legal basis. This study also focuses on the relationship between forest policies and local people in order to understand the origins of contemporary issues in state forests: illegal logging, smuggling, overlapping land rights, and serious environmental degradation.

The extent of local people’s collaboration with or acceptance of the state forest system is crucial in understanding the issues. Many physical tasks in forestry, from planting trees and caring for them, cutting them down, and hauling out the timber, are carried out by people from the surrounding area. If local people are hostile, sound management of the forest is impossible—they can easily engage in acts of sabotage, such as setting fires. On the other hand, if local people actively participate in forest conservation and reforestation, government programs will be successful and harmonious relations between the people and the state can be attained.

The relationship between the state Forest Service and local people during the colonial era has been discussed by Peluso, especially in the context of the Saminism Movement (Peluso 1992, 69–72). However, it is important to remember the exceptional circumstances that gave rise to the movement: the staunch refusal of the people to pay taxes as they were at odds with the rest of the colony, and, furthermore, the specificity of their actions within Central Java. Peluso also discusses timber theft, explaining how the forest police investigated the teakwood used by local people to build houses and accused them of having stolen the timber (Peluso 1992, 73). Despite the fascination with Saminism, it was unquestionably circumscribed within a small area; and therefore it is also essential to acknowledge the actions of those living in Java more generally. Based on these considerations, this study asks the following key questions: How did the idea of state forests emerge? What role did state forests play in the exploitation and conservation of forests as well as reforestation? What was the role of state forests in the economy of the Netherlands East Indies, including infrastructure development? Which policies affecting local people were implemented by the colonial government, and how did local people respond to these policies? How successful was the system in collaborating with or controlling local people so that harmonious relationships could be created? Finally, what were the reasons behind the successes and failures of the system? This paper will attempt to answer these questions.

I The “Forest” in Indonesia

Rural people in Cianjur District claim that the Indonesian word hutan (forest) refers solely to state forest, that is, kawasan hutan. When the author asked the same people how they referred to the forest area under their ownership, they replied that those lands were called talun or pasir in the local Sundanese language. Talun refers to productive fallow land that resembles a forest area during the fallow period, while pasir is the word for dry land located on the slopes of a hill or mountain on which various trees and plants grow (Mizuno and Siti 2016).

Pertinently, official government data on forest areas are always confined to the area of state forest. Forest areas are recorded yearly in the Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia, published by Central Bureau of Statistics (Badan Pusat Statistik).

According to the yearbook, the forest area in Java was 2.99 million ha in 1963, 2.891 million ha in 1973, 3.025 million ha in 1998, and 3.055 million ha in 2004.2) These data are consistent with those collected during the colonial period. Forest areas in Java amounted to 2.464 million ha in 1930 and 2.72 million ha in 1937.3)

It seems irrefutable that the current forest policies and the overall forestry system are a legacy from the colonial era. The Dutch East India Company besieged Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in 1619 and from this base slowly expanded its control. The Company needed timber, especially teak, for bridges and palisades as well as other infrastructure. The timber was supplied through the imposition of the compulsory delivery system under whose terms the head of the local regency gave orders for the procurement of timber felled and delivered by corvée labor (blandong). This was called the blandong system (blandong stelsel) or the compulsory timber delivery quota system (houtcontingent) (Paulus 1917, 386). Deforestation proceeded apace in West Java, Semedang, Central Java, Pemalang, and the Demak area. The deforestation crisis that began under the aegis of the Dutch East India Company reached such proportions that it required a major reform of the system at the end of the eighteenth century (Boomgaard 2010, 53–57).

Herman Willem Daendels, who had been the governor-general in Batavia since 1808, attempted administrative reforms that included the appointment of a special administrator for forest management directly attached to the office of the governor-general, a rotation system of tree felling and planting between designated parcels, and the payment of wages to those who had performed the blandong. One of the most important reforms was the declaration of land designated as state domain; this extended to all forests, as Daendels maintained that forests should be used in the service of the state (Schuitemaker 1950, 38–39). At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a forest commission concluded that the areas of forest located in government-controlled territory were state owned. The forests were to be planted with trees that served a useful function and to be properly cared for in order to yield the best profit (Boomgaard 2010, 57). A charter was drafted in 1804, during the transition from the Dutch East India Company to the Dutch East Indies administration. Under it, the Bataafse Republiek (Batavian Republic) stipulated that all forests in Java would become the property of the state (Soepardi 1974, 20).

The English interregnum government (1811–16) discontinued this reformed system because it deemed it too expensive. After the colony was returned to the Dutch, the system was reintroduced but on a smaller scale in Rembang (Central Java), while the old compulsory delivery system was retained in the rest of the area where it had been introduced by Daendels. However, the idea that all forests were state domains was maintained. In 1830, the constitution stipulated that any forests containing teak (not sold or conceded to any particular person) throughout Java and Madoera (hereafter referred to as “Java”) were officially state property under Article 79.4) This article also stated that nobody could fell these trees unless a permit had been obtained from the government through official channels. This stipulation was repeated in 1836.5) The constitution of 1854, known as the Government Regulation (Regeringsreglement6)), stipulated that the governor-general had to pay particular attention to teak forests and ensure that the state’s property rights were upheld. These rights were not to be sold or conceded to any private individual (Article 61).

The stipulations on teak forests were extended to the forests referred to as wildhoutbosschen (wild timber forest) in 1864, with a wider implementation of regulations relating to tree-cutting permits.7) E. H. Brascamp (1922, 1095–1096) noted that the forests in Java were part of the state domain, as long as no exceptional rights could be claimed in particular instances. This remained the case until 1864. Around 1860, there was a discussion on how forest policy should be reformed after the serious deforestation under the cultuurstelsel (Cultivation System) introduced in 1830 and the abandonment of the forced labor-dependent forest exploitation system (blandong) (Mizuno and Retno 2016). A committee was formed in 1860, and experts from the Supreme Court and the Departments of Agriculture and Forest Policy drafted a comprehensive forest law in 1861. This suggested the notion of a community or village forest; however, a high-ranking official of the Supreme Court criticized the idea, saying that if a forest was viewed as the property of a village based purely on its proximity to the village, all forests would have to have been reconstituted as community or village forests. The ideas of a community forest and a private forest were rejected and erased from the draft, leaving “state forest” as the only recognized category, although some villages were thought to be able to have limited rights to the forest (Departemen Kehutanan 1986a, 71–79). Finally, the Timber Forest Act in Java and Madoera in 1865 reserved the designations of teak timber forests and wild timber forests as state land (Van de djatihout-bosschen, welke de eigendom zijn van den lande and Van de wildhout-bosschen, welke de eigendom zijn van de lande, respectively).8) To administer these forests, the Forest Service (het Boschwezen), a bureau responsible for overseeing forestry-related issues, was clearly defined its task and formation of staffs according to the purpose of the Act. The Regulation for the Management and Exploitation of the Forests in Java and Madoera in 1874 (Reglement voor het beheer en de exploitatie der bosschen op Java en Madura9)) specified state-owned teak forests (van ’s lands djatibosschen) and state-owned wild forests (van ’s lands wildhoutbosschen). Both regulations carefully stipulated the ways in which these forests could be exploited by contractors from private industries, who could dispose of the timber freely after paying a yearly lease tax or by supplying the timber to the government; payment was determined by the amount of timber cut, expressed with the timber volume of M3.10) Forests were owned by the state, and exploitation was first carried out by private contractors but later monopolized by the state (see below).

The Forest Service Regulations (Boschwezen Reglementen) of 1927 defined forests located on state land even more specifically.11) Article 2 stipulated that forests on state land (van de bosschen van den lande) could be defined as land belonging to the state (het landsdomein), in which no right of disposal could be attributed to a third party. The article gave five specific definitions: land covered with (1) naturally growing timber and bamboo; (2) trees planted by the Forest Service (Dienst van het Boschwezen); (3) state roads and tree parks not established by the Forest Service, as long as these were administered by the authorities under orders from the Forest Service; (4) trees planted by the higher authorities; and (5) parks consisting of trees in which no trees were supplied or established by the Forest Service. These could also include land not covered by trees but surrounded by the above-mentioned types of land, as long as the land was not disposed of by the authorities or by agencies other than the Forest Service. Furthermore, Article 2 included land reserved by the authorities in the interests of conservation or forest expansion, as well as plots of land incorporated by the regulations on the borders of forests.

The regulations dealt only with forests on state land. The Forest Service Regulations (Boschwezen Reglementen) of 1932 were titled Bepalingen met betrekking tot ’s lands boschbeheer op Java en Madoera (Provisions relating to the management of state forest in Java and Madoera). Therefore, as before, only forests on state land or state forests were recognized and covered by the regulations. This was based on the principle that all forests were state property, which had held since the beginning of the nineteenth century, especially following the conclusions drawn by the committee of 1860 mentioned above. People could make use of forests with the permission of the state or in some other limited way (see below).

As Peluso (1992) as well as Vandergeest and Peluso (2006a; 2006b) have emphasized, German scientific forest management was introduced to Java, but the forest that the government sought to regulate there was only officially designated state forest. On the other hand, in Japan, where the German scientific forest management system was also introduced, at the end of the nineteenth century there were various categories of forest, such as state forest, community forest, public forest, and private forest—like in other countries, as discussed below. Japan’s Forest Act of 190712) stipulated the formation of forest unions or forest cooperatives (森林組合 shinrin kumiai) that organized private foresters, in the manner of Germany’s forest unions (Waldgenossenschaften) or forestry unions (Waldbetriebs–genossenschaften).13) Consequently, one of the characteristics of forestry in Java which diverged from the German template was that only state forests were recognized and managed by the government’s Forest Service (private companies were involved as contractors); the categories of private forest, community forest, public forest, and forest unions (cooperatives) were not included.

After Indonesia’s independence in 1945, the government continued to emphasize the idea of state forests. This concept had been laid down in the Forest Service Regulations of 1927 and was pretty much perpetuated by the Undang-Undang Pokok Kehutanan (Basic Forestry Act) in 1967—the first comprehensive law governing the Forest Service after independence. Article 5 of this law stipulates that “forest” is defined by the government as land on which whole trees may be found alongside a cluster of natural resources in natural environments, as well as natural environments that are designated as forest by the government (even if there is no forest there). The extent of the state forest area was designated by the minister of forestry.

Under the terms of the law, state forests (hutan negara) covered forest areas where no property rights existed. They consisted of protected forests (hutan lindung), forests that served as sites of production (hutan produksi), reserved natural forests (hutan suaka alam), and forests utilized for tourism (hutan wisata). Besides these categories, privately owned forests (hutan hak) were stipulated; however, the policy on this matter was implemented only to a limited degree, for instance, a forestation policy (penghijauan) for the area outside the state forest was differentiated from reforestation (reboisasi) in state forest (Departemen Kehutanan 1986b, 96–99).

It is significant that when researching areas of forest during this period, usually only government-designated forest areas are discussed, and no detailed data on privately owned forests are available.

In any discussion on the formation of state forests, the relationship between the land rights of local people and state land should be mentioned, albeit briefly. Article 62, Clause 6 of the 1854 Regeringsreglement (governing regulations), the constitution of the Netherlands East Indies, stipulated that land that indigenous people (inlanders) had cleared for their own use as community pasture or for other purposes belonged to the villages and could not be disposed of by the governor-general except for public benefit based on Article 133 (on expropriation) or by any other higher authorities for cultivation. These measures could be put in place only with the payment of proper compensation. Article 62, Clause 5 stipulated that any land concession granted by the governor-general would not violate local people’s rights.

The 1870 Agrarian Law (Agrarisch Besluit)14) stipulated that retaining Clauses 2 and 3 of the previous law (Article 62, Clauses 5 and 6 of the Regeringsreglement) meant that any area of land for which proof of property rights could not be provided would be considered state land (domein van de staat). This policy was called the declaration of state land (domeinverklaring).

Therefore, all land in Java, excluding land to which property rights pertained and that only Europeans could hold, became state land.15) However, the local people’s land rights to state land, including those based on communal customary law, could not be trampled on by the authorities, under the Regeringsreglement of 1856 and Agrarisch Besluit of 1870. Communal customary right was categorized as beschikkingsrecht (customary communal right of disposal or right of avail) by C. van Vollenhoven; it encompassed the right of disposal of land with all due respect for customary restrictions (Vollenhoven 1932, 8–9).

According to Vollenhoven’s interpretation, when the Regeringsreglement of 1854 and Agrarisch Besluit of 1870 became law, land belonging to villages was interpreted as the overall surrounding area of the village, including forests, pastures, returned wasteland (land unused by villagers who had left the village), settlement areas, cultivated land, and so on. The right to clearance of wasteland was also included. A proposed amendment submitted by a member of parliament to limit the right of avail (beschikkingsrecht) of the village—or, in other words, to limit the land belonging to the village to only the actual settlement area, cultivated land, and pastureland—was rejected. Despite these discussions during the process of legislation, Dutch administrators in Indonesia tended toward a narrow interpretation by excluding forest, uncleared land, and even pastureland (Vollenhoven 1932, 65–82). This was also upheld on the level of legislation. The Clearing-Land Ordinance (Ontginning Ordinantie) of 187416) and Agricultural Matters (Agrarische Aangelegenheden) of 189617) stipulated that land belonging to the village was land that had been cleared and was still used by local people, settlement areas, roads, and so on. The clearing of state land other than community pastureland or land for other reasons belonging to the village by local people required a permit from the administrators. Clearing land without a permit was punishable with a fine of public labor without pay for one to four weeks. These stipulations were interpreted as bans on shifting cultivation and deforestation (roofbouw en ontwouding) by the local people (Bezemer 1921, 394).

The Undang-Undang Pokok Agraria (Basic Agrarian Act) of 1960 recognized the claims of customary law and stipulated that property rights were to be based on customary rights. The Act assumed that Indonesia as a whole was a customary body, so the state had the supreme right to control the entire country (hak menguasai dari negara)—in the same way that the village had the right to control land belonging to the village. People’s rights were recognized. However, land for which particular rights such as hak ulayat (customary communal rights) could not be proven would eventually fall under the direct control of the state (tanah yang langsung dikuasai dari negara). The upshot was that vast tracts of land ended up falling into the hands of the state, even after 1960.

The colonial government implemented other forest policies, especially after 1860. The Forest Service made efforts to expand the forest by establishing state forest boundaries through surveying and mapping, building fences, and expelling people. It prohibited grazing, forest clearing, swidden agriculture, wood collection, and grass cutting by local people. In the 1870s, private companies began to get involved in forest management as contractors. However, after the 1900s full state control and wider exploitation of the forest were established—not only for the purpose of conservation but also to meet the growing demand for timber (Eyken 1909; Stibbe et al. 1919; Peluso 1992; Vandergeest and Peluso 2006a; 2006b; Mizuno and Retno 2016).

The Forest Service succeeded in expanding the forest area from 1.71 million ha in 1913 to 2.72 million ha in 1938. Policies that were hostile toward local people—for instance, the prohibition of slash-and-burn, grazing, the gathering of firewood and weeds, and charcoal burning—were contested by the local population, who resorted to setting fire to forest areas in protest both during the colonial era (Jelen 1928) and after independence in 1945 through solidarity actions uniting trade unions and farmers organized by the leftist movement (Peluso 1992, 105–121).

The Forest Service was taken over in Java by the State Forestry Company, known by the acronym Perhutani, throughout the 1950s and 1970s (Departemen Kehutanan 1986b).

Considering the history of forest policy in Indonesia, it is quite natural for people to think that hutan referred—and still refers—solely to state land and government forestry. During the Indonesian financial crisis in 1998, government forests—not private property (private forests)—were looted. In Cianjur District, where looting in the state forest area was rampant from 1998 to 2001, private land was left unscathed because people were personally acquainted with the owners of each plot of land and refused to destroy trees owned by fellow villagers or people in neighboring villages. Local people believed that looting in the state forest had been organized by staff members of the State Forestry Company18) (Mizuno 2016, 173).19)

II Establishment of the Forest Service

It was Governor-General of the Netherlands East Indies Daendels who introduced a new bureaucratic system at the beginning of the nineteenth century to replace the compulsory delivery (blandong) system mediated by the regents, local heads of the regencies. Daendels’ purpose was to abolish the compulsory delivery system, which relied on corvée labor (houtcontingenten en herendiensten), and relieve the regents of their authority by establishing Forest Service districts (boschdistricten). Forest administration was placed under the aegis of an inspector-general (inspecteur-generaal) and his staff in Semarang, while the management of each forest district was entrusted to forest managers (houtvesters) and forest rangers (boschgangers) who organized the workers. The blandong workers continued to be used under the new system, but now, besides being exempted from other corvée labor (herendienst), they were allocated rice fields and paid wages for their work in the forest (Paulus 1917, 386). Daendels did his best to introduce reforms, but his work was not continued under the various governments that followed him; and the corvée system was exploited to the full under Johannes van den Bosch’s Cultivation System after 1830.

Amidst growing criticism of the corvée system in forests under the guise of blandong, the system was abolished in 1865. The rearrangement of the Forest Service in 1865 marked a partial revival of the bureaucratic forest administrative system. After the abolition of the Directie van Cultures, the new and improved Forest Service (het Boschwezen) was brought under the Department of Home Affairs (Departement van Binnenlandsch Bestuur) in 1866. One of the changes it introduced was the making of forest maps. In 1871, 1:10,000- or 1:25,000-scale forest maps were made for each residency. In the 1880s the map resolution was improved to 1:5,000. Furthermore, after 1865, strenuous efforts were made to incorporate the activities of private companies that either logged and sold timber after paying the government a certain fee or were contracted to supply timber to the government. In Rembang—one regency that contained expansive teak forests—open bidding that included private companies was conducted, leading to the signing of development contracts with companies. Forest development based on contracts with private companies increased during the liberal economic period, which commenced in the 1870s when the private companies that dislodged the government-managed Cultivation System from 1830 to 1865 took over the principal role in export-oriented agricultural production (Eyken 1909, 8–10, 31–45).

The task of the Forest Service was to extract maximum direct and indirect benefits from the forests, which were divided into two types: a forest could be designated a production forest (gebruiksbosschen) or a conservation forest (klimaathoutbosschen), based on environmental considerations. Many of the production forests consisted of teak forests from which timber mass was extracted. Conservation forests were comparable to protected forests (Schutzwaldungen) in Germany, which were thought to influence the climate; these wild timber forests were intended for conservation (in stand gehouden), taking into account both the climate and hydrological and sanitary conditions. Most wild timber forests (wildhoutbosschen) were conservation forests intended to prevent erosion and degradation. Only parts of wild timber forests were economically profitable; on the other hand, production forests were intended to yield as much profit as possible for both timber use and the state budget, including the export of teak. High-quality teak timber from Java was preferred by many countries—especially in Europe—for construction purposes, including shipbuilding, dikes, and military equipment (Eyken 1909, 10–12, 21–35).

By the end of the 1890s, however, amidst growing suspicions that the activities of private companies during the liberal economic period had resulted in the impoverishment of the population in general, development contracts made with these companies came under fire, with critics claiming that profits that should rightly have gone to the state were being diverted to private companies. Moreover, many contemporary management analyses indicated that state-directed development (staats-exploitatie) was more efficient in terms of sustainability and cost-benefit analysis. Private companies left behind nothing when they cut down trees: newly growing sprouts were killed, and young potentially high-value trees were also felled. Many useful parts of trees, such as their edges, were left behind after the trunks were transported. The state apparently had more competent personnel than did private companies and also saved on cost (Eyken 1909, 31–45).

The Forest Regulation (Boschreglment) in 190520) opened the door to forest exploitation by the government of all state forests, replacing the exploitation by private companies (Eyken 1909, 35). In 1914 the system of private company contracts in Java was abolished, marking a shift from private toward state-directed development, that is, forest maintenance, management, and development by the forestry agency. The Forest Service was later placed under the Ministry of Agriculture (later called the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Trade).

At the beginning of the twentieth century, deforestation had become so severe it was leading to serious forest fires in 1905,21) among other alarming events. Around 1914, Java had 680,000 ha of teak forests and 1 million ha of other forests: a total forest area of 1.68 million ha. This area represented only 13 percent of the total land area of Java—far below the corresponding shares of Germany (26 percent) and Russia (37 percent) (Paulus 1917, 25).

Thereafter, the government undertook sustained efforts to increase the forest area in Java. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Forest Service began to publish an annual report that not only reported separately on the areas of teak and other forests (wildhoutboschen) managed by the state but also noted their respective boundary changes. The areas of these forests were gradually increased year on year by assigning new areas to be placed under the control of the Forest Service (both teak and other forests), changing the status of certain forests from other forest to teak forest, or by producing more accurate data through surveys and accurate mapping.22) The reports also began to include data on the amount of timber supplied, volume of firewood sales, and revenue from sales on state forests, as well as the costs of and progress in the construction and repair of forest roads and bridges. They also furnished information about promoting the selection and planting of disease- and pest-resistant tree species, restrictions on the excessive growth of cogon grass (Imperata cylindrica), and construction of lodging houses for Dutch and Indonesian staff.23)

The Forest Service contributed a great deal to the economic infrastructure of the Netherlands East Indies. It invested in the construction of roads, railways, bridges, and fire protection belts. It also supplied timber for construction by the government, companies, and local people along with firewood for companies and local people. For example, it supplied 13,436 M3 of timber for sleepers, bridge girders, and switchboards for state railway construction in 1906. For private railway construction by the Semarang-Joana and Semarang-Cheribon Steam Tramway Company (De Samarang-Joana en Samarang-Cheribon Stoomtram Maatschappij), the Forest Service supplied 5864 M3 of timber. Total exports were 64,914 M3, mainly to Europe and Transvaal, and supply for domestic use was 153,000 M3 (Eyken 1909, 40). The Forest Service made use of production forests, especially teak forests, to secure its own budget; it also created a net benefit to contribute to the state budget. For example, in 1905 it generated revenue amounting to 3.21 million guilders, mainly from taxes on private companies that contracted with the Forest Service. This revenue was sufficient to cover the expenditure of the Forest Service, including salary, forestation, and expenses to build roads, bridges, and houses amounting to 1.78 million guilders.24) Expenditures by the Forest Service made up only 55.5 percent of revenue, which created a big net budget surplus (batig saldi): 1.44 million guilders. This net profit contributed significantly to the state budget: 146.76 million guilders in 1905.25)

This policy—of revenue from the Forest Service covering its expenditure, and moreover creating a net surplus for the state budget—continued. In 1927 the Forest Service generated revenue amounting to 21.09 million guilders, mainly by selling teak and other timber, firewood, and charcoal to consumers; on the other hand, its expenditure was 13.97 million guilders. By this time the expenditure was 66.2 percent of the Forest Service revenue, so the Forest Service covered its entire expenditure and created a net budget surplus of 7.12 million guilders26) for the state budget; the latter had revenues amounting to 701.9 million guilders and expenditure of 764.62 million guilders in 1927.27)

For the Forest Service, which had made all efforts to extract benefits mainly from production forests, to conserve the forest by preventing erosion and degradation, and to enlarge the forest area, the main enemies were illegal logging, clearing, and grazing by local people.

In its annual reports, the Forest Service explained that since 1900 it had had to demarcate boundaries and had resorted to driving stakes into the ground to prevent “damaging and illegal development” by local people as well as to counter the persistence of large-scale illegal logging. In addition, the reports explained that lodgings had been built for the Indonesian staff (referred to as indigenous or native staff—het Inlandsche personeel) to protect them from malicious revenge by local residents and allow them to carry out their duties.28)

Forest protection was also an important goal; the reason given for this, besides illegal logging and forests fires, was the prevention of destructive attacks as a consequence of “unreasonable shifting swidden agriculture” (Beversluis 1937, 21) and “looting agriculture [roofbouw]” (Vollenhoven 1932, 24). This reflects the belief that swidden agriculture, which had already been prohibited by the 1874 Act, was a major contributor to deforestation. Efforts to conserve forests continued to expand with an eye to limiting damage by flood control, preventing erosion on mountain slopes, and creating forest stands to protect against the rapid spread of mountain fires and the like. In these cases, it was not the teak forests but wild timber forests that became important targets of maintenance, management, and expansion (Eyken 1909, 10–30).

A. J. H. Eyken (1909) noted that in addition to forest fires, overgrazing on fresh sprouts and saplings by animals, the collection of firewood and other forest products by local people, and the cutting of grass within forest boundaries by local people also contributed to deforestation. He argued that village leaders and police officers had to work together to supervise forest maintenance and management. He advocated that local people be prohibited from entering within the boundaries of state forests as well as carrying logging tools, making fires, carrying torches, and bringing cattle to graze within 100 meters of the forest boundaries. Cutting grass for cattle seriously damaged fresh sprouts and prevented reforestation. Eyken acknowledged that prohibitions against grazing, collecting firewood, cutting grass, and clearing land in the forest might give rise to conflict; however, he believed that public benefits should outweigh benefits to the local community. He showed a successful case of reforestation with the setting up of wire fencing on the slope of a mountain: trees within the fence were protected from damage by local people and grew well (Eyken 1909, 16–18).

Here the Forest Service’s strategy for reforestation and forest conservation is clear: expelling local people, and prohibiting them from entering and approaching the forest. But in actuality, there were alternatives. As mentioned above, in the discussion of the area belonging to the village according to Regeringreglement 1854, village areas included forests, pastures, reclaimed wasteland, settlement areas, cultivated areas, and so on. But forests, uncleared land, and pastureland were excluded from the village area by colonial bureaucrats. So actually, there were village forests near the settlements. For example, the survey of village autonomy in 1926 (het Eindverslag over het Desa=Autonomie Onderzoek) found that people had nearby village forestland (desa-boschgronden) earmarked not only for the expansion of agricultural (swidden) lands but also for future timber needs for housing and village projects, or cattle grazing (Laceulle 1929a, 24). In Malang there was open land (woeste grond) surrounded by agricultural land, and people were conscious of their communal customary rights of disposal or right of avail (beschikkingsrecht), which satisfied their need to have such a pattern of land use (Laceulle 1929b, 503).

If we compare with Japan again, communal forests (入会地 iriaichi) there have a long history; they satisfy the needs of local people—such as for firewood, water, and fertilizer—and are managed by local people. Communal forests in Japan were formed through the initiative of local people confronting the higher powers from medieval times, or around the seventeenth century; and in many cases people paid taxes to the authorities (Furushima 1955; 2000). Around the end of the nineteenth century, when the Bureau of Forest was established and state forests were formed following the ideas of German scientific forestry, parts of the community forests were integrated into state forests because the government wanted to expand the state forests (Handa 1990, 57–66); but many of them were integrated into public forests that were managed by administrative villages (consisting of some traditional hamlets). Many communal forests were managed by hamlets, so public forests were combinations of community forests. Upon the formation of public forests, particular attention was paid to each hamlet’s interests, such as allocating places for weeding and pasturing. Each administrative village made a forest use plan that allocated the forest into three parts: production forest, conservation forest, and wild timber forest. The last one supplied firewood, charcoal, timber for housebuilding, and so on. Each household supplied labor for the conservation forest based on consensus at villagers’ meetings (Okama 1994, 48–119). Some communal forests were registered as second-class private forests, and some were registered as private forests, to avoid integration into the state forest. Private foresters were organized into forest unions that were obliged to collectively make plans for exploitation, conservation, forestation, or infrastructure building. The activities of forest unions were controlled by the government, which gave them subsidies according to what they did (Handa 1990, 70–72, 181–190). It is clear that in the case of private and public forests in Japan, local people participated or were mobilized in the activities of exploitation, conservation, and forestation. Japan’s Forest Act of 1906 specified state forests, public forests, and private forests in addition to forests owned by temples and shrines, and royal forests, as well as forest unions. In Japan in 1907, 25.9 percent of all forests were state forests, 2.7 percent were royal forests, 16.9 percent were public forests, 0.5 percent were owned by temples or shrines, and 53.9 percent were private forests (Handa 1990, 312). On the other hand, in Germany around 1908, the area of royal forests was 1.8 percent of all forests, state forests were 31.9 percent, public forests were 16.1 percent, institution-held forests (such as cloisters, universities, and so on) were 1.5 percent, forest union-owned forests were 2.2 percent, and private forests were 46.5 percent (Ham 1908, 118).29) Around the same time, the idea of forest unions was diffused to many other countries, such as Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Australia (Ham 1908, 115–132; Handa 1990, 185).

The Netherlands East Indies, which followed the ideas of German scientific forestry, had the opportunity to recognize community forests, private forests, and public forests, as mentioned above, along with forest unions; it also involved local people in the processes of exploitation, conservation, and reforestation. However, the colonial government formally recognized only state forests, and it managed the exploitation, conservation, and reforestation of state forests itself (partly private companies were occasionally involved in exploitation as contractors); it was hostile toward local people, based on the belief that they were always damaging the forest. Such hostility was not free from racial prejudice.30)

It was in this context that the Penalties and Police Regulations for the Forest Service (Straf en politiereglement voor het boschwezen) were enacted in 1875. The 1874 Regulations regarding the Management and Development of Forests in Java and Madoera (Reglement voor het beheer en de exploitatie der bosschen op Java en Madoera)—later the Colonial Ordinance (Koloniale ordonnantie) Regulations regarding Management of Forests on State’s Domain in Java and Madoera (hereafter “Forest Regulations,” Boschreglement)—were issued in 1897. The 1875 Penalties and Police Regulations for the Forest Service31) laid down both forest offenses (boschdelicten) and the penalties they entailed, as well as the regulations for police control within the forest. They specified fitting punishments for crimes against and violations of the forest administration rules in Java and Madoera that were not covered by the general penal code. They declared forest thievery (boschdiefstal) a crime—that is, the felling of one or more trees (either felling an entire tree or cutting off its parts) in a forest without the legal right to do so, as well as the illegal removal of timber or felled trees or branches (Article 1). The Forest Regulations also stipulated classifications of forest damage and degradation (boschbeschadiging), such as the felling of trees or cutting of branches that would have a deleterious effect on the forests’ value. Forest violations (boschovertredingen) also included pasturing or grazing cattle within the forest, burning part of a forest without proper permission, transporting timber without the appropriate documents, transporting whole trees or parts of trees before paying the requisite fees, clearing a forest without permission, and so forth. The regulations also laid down the duties of the forest police—consisting of police (mantri) and forest guards (bosch wachter)32)—who had to deal with such crimes and violations. The fines for each crime and violation were also stipulated. For instance, forest thievery was punishable by either a custodial sentence or forced labor without a leg iron for three months to one year, and a fine of 50 to 200 guilders.

By and large, the Forest Service was hostile to the local community. However, there were some policies that sought collaboration with local people; and local people were allowed some activities in the forest, under the watchful eye of the Forest Service.

Collaboration between local people and the Forest Service was realized primarily in the planting of a secondary crop (palawijo, such as dry rice, maize, cassava, sweet potatoes, vegetables) between rows of young teak trees. Pepper vines or jackfruit trees were also sometimes planted. This system was called bosveldbouw-methode or tumpangsari. The Dutch agronomist Buurman van Vreeden launched a trial in Pekalongan and Tegal in 1856 (Soepardi 1952, 49–50), and the system was applied generally in Java from 1881 (Soepardi 1956, 121).

Three systems were used to plant teak trees. One was to have local people plant them in a straight row, with secondary crops in between. The harvests from these secondary crops were given to locals in lieu of wages. This system was called tumpangsari, or contract-line planting (contract-rijencultuur). The second was to have local people plant teak trees in exchange for wages (wage labor-line planting or kuli-rijencultuur). The third was storage planting (opslag-cultuur), in which workers planted shoots from existing trees for a wage.

The tumpangsari (intercropping) system became so popular that by 1924, 91 percent of teak was planted in this way (Soepardi 1952, 49–51). The system brought benefits to both the Forest Service and local people, and it continues to this day under the same name. For example, in 2002 in Cianjur District, the Perhutani (State Forestry Company) gave farmers the right to cultivate 0.25–0.5 ha per household in the state forest. The farmers were not paid but were told they could harvest the secondary crops—in return, they were obliged to plant and protect teak or other designated trees (Mizuno and Siti 2016, 72–73).33)

The Forest Service brought benefits to local people by creating employment. People could find work in forest-based industries such as teak cultivation, non-teak timber cultivation, thinning, and cutting and carrying out timber to the connecting road, among other tasks (Wilde 1911, 222–227). Carrying, transportation, and other jobs were paid a standard 10 guilders per M3. In 1908, 218,000 M3 of timber were produced. Tasks of the Forest Service such as forest maintenance, the construction of roads, railways, warehouses, and houses, and so on created employment opportunities that paid 3 million guilders in wages every year (Eyken 1909, 44).

The crux of the matter was that although the system was beneficial to local people, it fell far short of covering locals’ need for timber, firewood, pastureland, and non-timber products. Additionally, the forest surrounding the village was regarded as the territory of villagers, and villagers could get timber in their customary ways. To address this gap, the government created the “permit system.” For example, the Boschwezen Reglement of 1875 stipulated that local people could cut and drag out timber for their personal use from the exempted trees listed in the attachment appended to the regulations, if they had the written permission of the district head and had paid a royalty to the state for trees less than 6 el in length (1 el was 69 cm), and so on—all, of course, under proper supervision.34)

The regulations around 1900, as announced in Staatsblad 1901 No. 20835) and 1907 No. 232,36) stipulated that under this system the residents (the heads of the gewestelijk bestuur, or provincial administration) in Java and Madoera were authorized to give local people permission to cut commercially valueless firewood and timber for agricultural tools and fencing in a designated area of the forest within the tentative set-up of the teak forest. As mentioned above, they also had the power to permit local people to collect fallen timber for firewood, agricultural tools, and fences in other protected forests (in stand te houden wildhoutbosschen), based on the people’s needs and circumstances. Residents also had the power to grant local people permission to cut and drag out trees for special purposes, provided they paid the state a fee (Wilde 1911, 222–223).

Managers of teak forests could give local people permission to gather dry sticks and fallen trees. The governor-general could give local people permission to cut and drag out trees from the state forest for use as agricultural materials in times of disaster. Poor people could take trees for their own use for a small fee. Local people could be given permission under particular conditions to let their cattle graze, to burn charcoal, and to collect bark, fruit, and other products from the forest (Wilde 1911, 222–223).

Under these systems, the Forest Service continued to expand the area of forest territory managed and developed under its jurisdiction. Specifically, the area of teak forests in the Java region was increased by designating new areas of teak forest, planting teak, and converting other forests to teak forests. Teak forests expanded from 645,000 ha in 190137) to 680,000 ha in 1913,38) 739,000 ha in 1920,39) 799,000 ha in 1930, and 815,000 ha in 1938.40) The area of the other forests subject to conservation and non-teak timber use grew steadily from 1.489 million ha in 192041) to 1.665 million ha in 1930 and 1.905 million ha in 1938.42) Accordingly, the total forest area, comprising both forest types and the percentage of total land area in Java accounted for by such forests, increased from 1.71 million ha (13.4 percent) in 1913 to 2.22 million ha (17.1 percent) in 1920, later increasing to 2.464 million ha (18.6 percent) in 1930 and 2.72 million ha (20.6 percent) in 1938. As of 1914, there were 31 active forest administration districts, averaging 5,000 ha per district. The amount of timber supplied by the Forest Service increased gradually. In 1898 its supply of timber in Java was 247,542 M3 (120,988 M3 teak timber, 126,554 M3 other timber) and firewood was 507,779 M3 (266,877 M3 teak firewood, 240,917 M3 other firewood),43) while in 1937 timber accounted for 435,363 M3 (420,202 M3 teak timber, 15,161 M3 other timber) and firewood 1,101,416 M3 (868,483 M3 teak firewood, 232,933 M3 other firewood).44)

III Forest Security and Local People

According to the annual report of the Forest Service, illegal logging was a particularly serious issue in the 1900s. Below are some examples of this problem in the forest district (boschdistrict) of Tegal-Cheribon and its subdistricts of Pemalang, Tegal, Brebes, Cheribon, Madjalengka, Koeningan, and Indramajoe. In this forest district, there were around 22,003 ha of teak forest (Djatibosschen)45) and around 60,000 ha of wild timber forest (wildhoutbosschen).46) In December 1901, for example:

between 100 and 150 people from two villages entered the forest district in Indramajoe. and felled around 600 trees. Fortunately for the authorities, there were police mantri located in the West-Cheribon-Complex who responded quickly. If there had been no police mantri, no trees would have been left there.47)

Cheribon Residency was plagued by frequent large-scale robberies and illegal logging in the forest area in the last decade of the nineteenth century. In 1894 the forest manager (houtvester) reported large-scale degradation as a result. His successor also found a similar level of devastation in the forest a few years later. In 1901 yet more large-scale destruction was witnessed, with significant conflicts taking place in the forests of Indramajoe the following year. In these districts, timber thievery on private land (particuliere landerijen)48) was rampant on the western side of the Tjimanoek River. Incidentally, the opposite side of the river consisted of government forest, where the same situation was reported. The stolen timber was transported to Indramajoe or to the district of Gegesik-lor. The thieves did not seem to have encountered any transportation difficulties, otherwise so much timber could not have been stolen. If the thieves could not use the stolen trees themselves or sell them, they would have immediately ceased their nefarious activities. The authorities failed to locate the timber stolen from the forest in Indramajoe. Of all the suspects, only seven were punished. The others, who were found to be in possession of large quantities of timber, were all released because the judge was not convinced of their guilt. The author of the annual report of the Forest Service agreed with the judge that it was hard to ascertain whether the timber found in the homes searched during the investigation had been stolen or not.49)

Why were so many people involved in illegal logging? A. Neijtzell de Wilde (1911, 225) argued that local people generally felt no guilt about stealing trees from the forest because they considered at least the usufruct of the wild timber forest well within their land rights. In this case, the issue was whether the land belonged to the village or not. Government regulations such as the Ontginning Ordinantie of 1874 and Agrarische Aangelegenheden of 1896 stipulated that the clearance of state land—excluding community pastureland and land belonging to the village—by local people should be sanctioned via a permit issued by administrators. But it seemed that nobody bothered to obtain permission to clear land even within the state forest.

Dealing with permission to clear wasteland, or uncleared land (woeste gronden), the Survey of Decreasing Welfare of Indigenous People in Java and Madoera (Onderzoek naar de mindere welvaart der Inlandsche bevolking of Java en Madoera) included the question of whether people were asking solely to clear wasteland or were doing so mainly for the purpose of felling the standing trees and selling these to earn a livelihood. Local officers in Cianjur-Sukabumi said that no applications to clear wasteland had been found, while their counterparts in Sumedang said that no applications were possible under the current regulations. The forest manager (houtvester) of West-Preanger and Banten said that there was no need for applications to clear wasteland in order to profit from the timber harvest, as long as the managers knew what was going on. On the other hand, because there were applications to clear wasteland in relation to leasing the land to Chinese and Europeans, officers in Limbagan were warned to be on the lookout.50)

Discussing the permit system, Wilde said that its stipulations about asking permission were seldom or never used (in Djepara and Banywangi, and also in Djember), but in most other areas timber was stolen from state forests, and the amount stolen decreased where strict police watches were implemented (Wilde 1911, 225).

Forest theft was rampant in the districts of West Tegal-East Cheribon and West Cheribon, where the forests had already been seriously damaged. Many rivers and streams crisscrossed West Tegal and East Cheribon, and these were ideal for transporting timber over long distances within a short time—so after stumps were discovered in the forest, there was little chance of finding the offenders. In Koeningan, the majority of forest offenses consisted of illegal clearing in the wild timber forest. This was compounded by forest fires that constantly reduced the forested area. The best solution to prevent illegal clearing was to set up inspection checkpoints along the roads throughout the wild timber forest. Each instance of illegal clearing could then be immediately detected, making it very difficult for the culprits to get away.51)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were still large expanses of uncleared land or wasteland in West Java. The government attempted to keep these tracts as they were, especially in the state forest, and to encourage the expansion of wet rice fields in the plains, ensuring the designated reserve area for the village community in the state forest but preserving the permit system.

However, the clearing of wasteland, or uncleared land, took place everywhere, especially in the case of land that could be used for swidden agriculture. Officers in Sumedang complained that this activity was not covered by the Ontginning Ordinantie of 1874. A stipulated intervention by the government did not stop these clearings. The authorities had hoped that the ordinance (Ordinantie) would impose stricter regulations to curb what they considered “looting agriculture” (roofbouw, or swidden agriculture), but officers in Sukabumi and Soekapoera lamented that the Ontginning Ordinantie could not halt the spread of swidden agriculture by local people.52) In Sukabumi new settlements mushroomed because wasteland was no longer available in the older settlements and people did not have the means to buy new land. As they had always done, people moved to areas where the wasteland on which they hoped to cultivate rice fields could be cleared. A forest manager in East Preanger said there were extensive wastelands in the Preangan area on which people had no difficulty clearing land. On the other hand, erfpacht (75-year long-term usufruct land rights granted to European companies) was enforced here and there. Common people (de kleine man) already had abundant land there, and they had never applied for a permit to clear it. In 1904 the head of Cipeujueh in Soekapoera reported 78 cases of illegal clearance in his area. The common people did not practice permanent agriculture but used the land for huma, or dry rice, cultivation on swidden fields.53)

Around the same time, the need for timber was growing. Trees on plantations were being cut down to make charcoal. After the expiry of the land lease for a plantation, there would no longer be any opportunities to obtain firewood for charcoal burning. There were also plenty of illegal charcoal burners in the numerous sugar factories. Creating provisions to regulate the transport of charcoal could help reduce illegal clearing and wood theft for charcoal burning. In regions where there was a great need for charcoal, it would be worthwhile to set firewood fees at a reasonable level. Exorbitant firewood fees meant that contractors could not make charcoal without damaging the forest: without the wherewithal to pay for firewood, they would end up stealing it to make charcoal. By issuing a regulation stating that wood could be burned only on empty blocks, and with all authorized firewood already stacked (with the approval of a judge or the forest manager), offenses could be prevented.54)

Here we can see that setting up the royalty system might have benefited some people; but the system did not function well, so illegal clearing for charcoal burning persisted. Speculating on why local people did not make use of the permit system, Wilde noted that the timber area or forest designated under the permit system was too far from villages, so the cost of dragging out trees was very high. Moreover, locals were often not aware of the system, and even if they were, the fees were too expensive for many of them (Wilde 1911, 225). Quite simply, the procedure for obtaining permits was too complicated for local people.

The most significant effort the government made to prevent forest offenses at the beginning of the twentieth century was to increase the number of forest authorities on patrol. Certainly various efforts were made to uphold state property rights in the state forest (de eigendomsrechten van den staat om ’s lands bosschen). The situation improved in Grobogan Sub-province (afdeeling), partly as a result of the appointment of special staff and also because of the halt to tree felling on adjoining lease land belonging to Solo. The forest police strongly supported this difficult task. Favorable reports were also received about the situation in the forest districts of North Kruitan and Northwest Wirosari. The Toeder Forest District manager had earlier reported on the unbridled boldness of forest thieves. However, the situation gradually improved, and the number of thieves was kept in check by the beginning of the twentieth century.55)

The unfortunate situation in the Toeder Forest District was thought to have arisen in the first instance from the inadequacy of the police and forest patrol forces. The area was simply too big, and the fifty persons with degrees in forest science recruited by the Forest Service as new personnel barely made a dent. Second, local people did not fully appreciate or even grasp the need for forest conservation. Third, the methods by which forest offenses were judged were always completely dependent on the personal opinions of police magistrates, who were often biased and inconsistent. Pertinently, the punishment was also frequently not proportional to the offense.56)

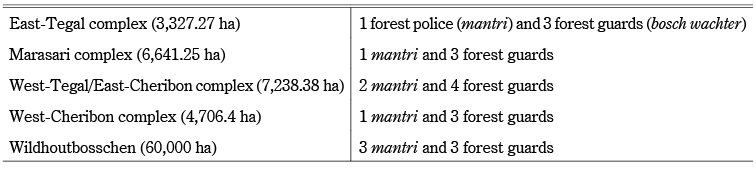

Table 1 details the number of forest authorities in place in five complexes.

Table 1 Number of Forest Police and Forest Guards in Some Forest Complexes

Source: Dienst van het Boschwezen (1903, 14).

From Table 1, we can calculate that the average areas per personnel within each complex were 831.82 ha, 1,660.31 ha, 1,206.4 ha, 1,176.6, and 10,000 ha, respectively, and therefore appreciate the size of the mantri’s area of responsibility at the beginning of the twentieth century.57) Generally the number of forest police officers was thought to be too small (Eyken 1909, 53). This area was too expansive for a mantri to cover properly, which led to increases in the number of mantris, as mentioned below.

More often than not, the theft of trees was motivated by the trees’ potential sale value rather than the people’s own needs. In many areas punishment was hardly a deterrent, as the probability of prosecution or imprisonment for such crimes was low. The profit to be gained by stealing wood from the forest was therefore well worth the risk of being caught.58)

From the cases cited in the Forest Service reports, it is clear that the colonial government was worried about the conduct of people in the state forests and considered a number of security-judicial approaches at the beginning of the twentieth century. The number of forest police on patrol was thought to be too low, so the government attempted to increase their numbers; and indeed, many cases were brought to court as a result of the forest authorities’ efforts. In fact, the number of cases became far too high for the criminal judges to deal with.

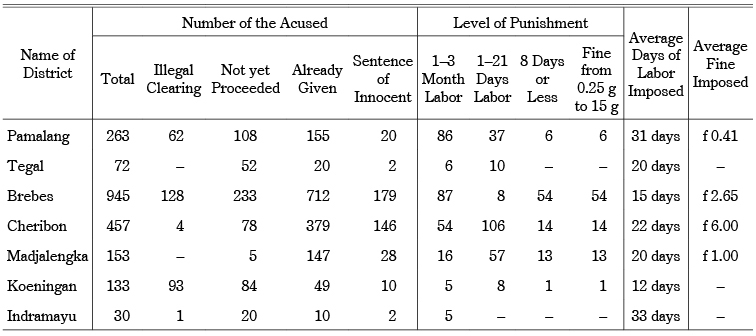

Table 2 shows the number of those accused of forestry-related crimes, the number of court processes, the level of punishment, and the average length of forced labor imposed and/or the severity of fines issued per case in 1901. The data also show how many cases were heard and the types of verdict (that is, how many were found innocent or guilty), alongside the various levels of punishment.

Table 2 Number of Accused Forest Offenders, Number of Cases in Court, Level of Punishment, and Average Days of Labor and Fines Imposed

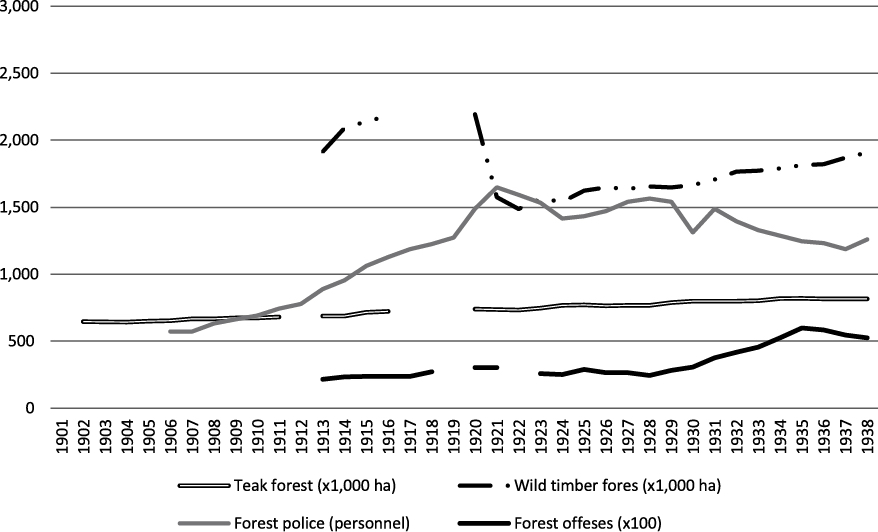

Fig. 1 covers the period from 1901 to 1938, detailing changes in the size of the teak forest area and wild timber forest area, plus increases and decreases in the number of forest police and number of forest offenses throughout that period. The size of the teak forest and wild timber forest areas has been divided by 1,000, and the number of forest offenses by 100. The number of forest police employed is displayed as raw data and so can be compared in a table.

Fig. 1 Area of Teak Forest, Area of Wild Timber Forest, Number of Forest Police Officers, and Number of Forest Offenses (1901–38)

The data in Fig. 1 show that the area of teak forest steadily increased, and that the area of wild timber forest also expanded, especially between 1923 and 1938. The number of forest police officers employed rose consistently between 1906 and 1921. After that, the number remained constant or sometimes declined slightly. Against these trends, the number of forest offenses constantly increased until the end of the colonial era.

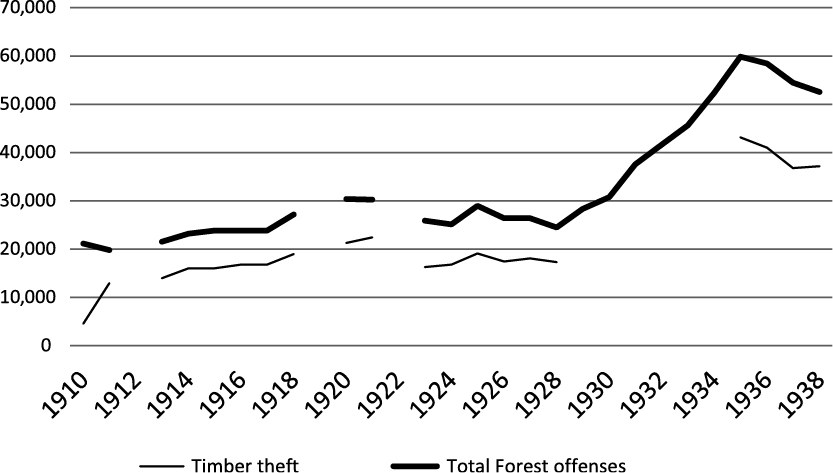

There were many kinds of forest offenses. The major crimes were timber theft, illegal clearing of the forest, illegal pasturing, burning of the forest, and charcoal burning. Fig. 2 shows the long-term changes in the frequency of forest offenses and timber theft.

Fig. 2 Incidence of Timber Theft and Total Forest Offenses

As described earlier, timber theft was motivated principally by the value of the sale of timber or timber extracted for a particular purpose (that is, for use in local people’s houses). In the Todanan Forest District, large-scale firewood theft took place in 1902 after the development of the lime-calcining industry in villages surrounding the state forest. In Ngampel village on the Remman-Blora post road, there were many kilns that had permission to burn lime, although they did not have permission to either excavate limestone or chop down firewood. It was difficult for the forest police to patrol this area because the kilns were located outside the state forest. This ambiguity led to the forest being significantly degraded.59) In Cheribon Residency, large-scale timber theft was rampant in 1920, and many businesses were complicit either in the direct theft of timber or in receiving and selling timber. These businesses reaped large profits as a consequence of the high price of timber.60)

Various businesses were developing at the time, and both charcoal and timber sold well, as both were important sources of energy. It was also a period in which lime kilns, brickmaking, roof-tile making, pottery making (Rouffaer 1904, 77–90), and sugar mills were all taking off in Java.

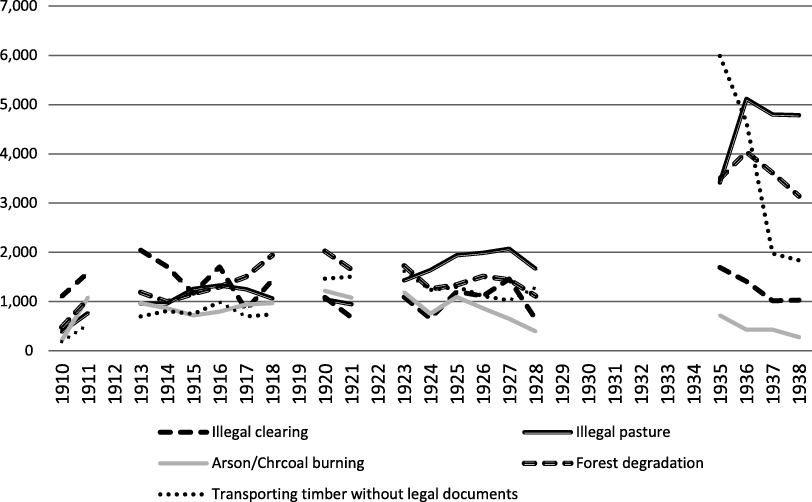

Although timber theft loomed largest, there were many forest offenses. Fig. 3 shows the nature and frequency of forest offenses besides timber theft, although data from 1929 to 1934 are unavailable.

Fig. 3 Nature and Frequency of Forest Offenses besides Timber Theft

The data available include the number of charcoal-burning offenses and the frequency of setting fire with malicious intent (or arson) in the forest by local people. There was an unmistakably increasing trend in forest offenses.

Forest fires broke out very often in 1911, mainly because of the dry east monsoon wind. Fires had also been prevalent the previous year, partly as a result of accidents and partly due to arson perpetrated by local people. To deal with the cases of arson, by far the most significant source of such fires, intensive police surveillance was carried out, despite the small number of police officers available. The harsh actions taken by the police against cattle breeders, alang-alang grass cutters, and other violators of the Forest Regulations often provoked arson in retaliation. This was easily perpetrated in areas with fewer policemen on patrol. The opposite could be observed in areas with plenty of police officers, with fire being limited to small areas.61)

A Forest Service report on the period between 1921 and 1922 states, “It is often said by the majority of forest managers that a large number of forest fires are the result of malicious intent or acts of revenge perpetrated by people against the forest or village police.”62) It is obvious that forest fires as the people’s expression of discontent were of real concern to the Forest Service.

The number of forest police and offenses constantly increased after the beginning of the 1910s. The importance of forest policing and the insufficient number of forest police personnel had been a constant complaint, explaining why the number of personnel was increased from the beginning of the twentieth century. It was hoped that cooperation between the forest police and the village police or village administration would also increase.

The cooperation between the village and district police in the sub-province (afdeeling) of Demak still left great room for improvement. There are many proven facts that show this. For example, in the previous year, a large amount of timber was found [to have been used] for the purpose of home garden cultivation. Two village heads were found to have granted permission to fell forest trees for the purpose of constructing agricultural gardens and fences. The village heads were warned not to misuse their authority in this instance.63)

This case shows that although the actions of the village heads benefited the villagers, the latter were considered guilty of a forest offense by the authorities. Eyken (1909, 53) lamented that local people as well as village officers considered the punishment for timber theft and illegal clearing as nothing dishonorable. Since the number of forest police officers in Toeban was only 27, while the village police and district police numbered two thousand, it was only with the support of village police that forest police could perform their functions effectively.

Around 1920, there were serious discussions on how to control the problem of timber theft. An additional proposal was put forward: a new investigative department would be set up under the authority of the district head and supervised by the head of the police office and the residents. The police office would collaborate with the forest police division to catch thieves on the ground. The police office would therefore be actively involved in preventing forest offenses, with the district office backing the forest police. The proposal was implemented in a part of Cheribon Residency in 1921. Six mantris and 11 forest guards were employed in the Cheribon complex, which covered the Karawang-Indramajoe, West-Cheribon-Soemedang, and East-Cheribon-Tegal Forest Districts in 1920. Each forest guard was assisted by two investigators, a police inspector (politieopziener), a forest inspector (boschopziener), a forest controller (houtvester), and local administrative officers. However, the results were disappointing. There were many new instances of illegal logging, especially in the ravines. Suspicions were raised, and it turned out that police officers were patrolling only the easily accessible areas of the forest. Ultimately, the trial was written off as unsuccessful and the conclusion was that the forest police and forest guards would be better suited to assuming the responsibility of forest control.

The following year, a revised plan was proposed whereby police officers would be organized by the Forest Service and expected to assist the forest police in instances where the latter were not placed under the authority of local administrative officers. This method was tested in Cheribon in 1921 despite widespread objections. Finally, the system of collaboration between the police officers and the Forest Service was altered as follows: (1) police officers were placed under the authority of the Forest Service office in the forest; (2) outside of the forest, police officers were under the control of local administrative heads; (3) the forest police force was under the control of the Forest Service; and (4) the investigation department was abolished. Under this system, central leadership was in the hands of the Forest Service, and in the event of urgent and important cases, the forest guards and forest police were assisted by local police officers. The village police and general police provided help, and in emergencies the assistance of the field police was obtained. Forest managers took over the management that was previously the task of local government officers. Orders were issued by the wedono (head of subdistrict). Liaisons with the general police force had to be initiated by the Forest Service.64)

Finally, a system was established in which the forest guards were fully managed by the Forest Service. Given the extent of their responsibility in apprehending forest thieves, the district heads were to be kept fully informed at all times. This gave local government officials the chance to prepare themselves to provide backup. When matters became particularly bad, local people could be brought in to collaborate with the Forest Service and the local administration, working alongside police officers.

After the establishment of a system of collaboration between the Forest Service and the local administration, especially between the forest police and regular police officers, the number of those employed as forest police did not increase from 1920. However, the number of forest offenses did not decrease. The Forest Service failed to establish an efficient system to curb the number of forest offenses despite collaborating with the local administration, the police, and the judicial system, which were very much on the alert for this very purpose.