Contents>> Vol. 13, No. 1

Narrative and Framing of a Pandemic: Public Health Communication in the Vietnamese Public Sphere

Mirjam Le* and Franziska Susana Nicolaisen**

*Chair of Development Politics, Faculty of Social and Educational Sciences, University of Passau, Dr.-Hans-Kapfinger-Str. 14 d 94032 Passau, Germany

Corresponding author’s e-mail: mirjam.le[at]united-le.com

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8611-8445

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8611-8445

**Chair of Development Politics, Faculty of Social and Educational Sciences, University of Passau, Dr.-Hans-Kapfinger-Str. 14 d 94032 Passau, Germany

e-mail: franziska.nicolaisen[at]gmx.de

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1991-4035

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1991-4035

DOI: 10.20495/seas.13.1_35

This paper explores the Vietnamese government’s approach toward public health risk communication in the context of citizen mobilization during the Covid-19 pandemic. We analyze the government’s communication strategy using images and videos published during the pandemic, such as artwork, leaflets, campaigns, music videos, and public announcements in public spaces. The government’s visual risk communication strategy is embedded in an idealized vision of cooperative citizenship. The focus is on the moral obligation of citizens toward the Vietnamese nation and the morality of caring, in which the state communicates behavior it deems morally correct.

Keywords: Vietnam, public health, risk communication, Covid-19 pandemic, cooperative citizenship, authoritarianism, morality of caring

Introduction

With the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Vietnamese government’s response became a controversial topic in the global discourse. Consequently, an extensive body of literature was published in newspapers, books, and academic journals addressing the subject (Le Huu Nhat Minh et al. 2021; Le Tuyet-Anh T. et al. 2021; Nguyen et al. 2021). While some Western media outlets pointed toward the underlying authoritarian government structures as the reason for the initial success of Vietnam’s response (Hayton and Tro 2020), academic literature looked at the role of public communication strategies and nationalism (Nguyen Quang Dung 2020; Taniguchi 2022). Vietnam was also held up as a model case for the Global South (Dabla-Norris et al. 2020; Tran et al. 2020).

The pandemic thus provided a unique tool for looking at policy making in Vietnam in action, including its underlying narratives concerning state-society relations. This is particularly interesting in the context of a global democratic backslide and the emergence or hardening of authoritarian structures. Looking at Covid-19 policies, regulations, implementation, and communication can be useful to better understand the conceptualization of these relations in the authoritarian context of Vietnam. Citizenship, as proposed by Ward Berenschot et al. (2016), can be a useful concept for understanding the complexity of state-society relations. As the pandemic progressed, state and social actors in Vietnam were forced to renegotiate their relations. Consequently, the Vietnamese framing of citizenship was also used as a tool by the authorities to mobilize the population, enforce compliance, and create legitimacy for the government and its regulations. The public health crisis provides the background to study the production of narratives on citizenship as they are used to frame the pandemic for increasing social mobilization.

Consequently, this paper looks at Covid-19 communication in Vietnam (particularly from February to August 2020) to reconstruct the narratives used by state actors for citizenship negotiations. It aims to better understand the distinct conceptualization of citizenship for Vietnamese state-society relations in the context of a public health crisis.

Cooperative Citizenship

In recent years, the focus of state-society relations in Vietnamese studies has moved away from a state-centered perspective, where citizens merely negotiate the top-down politics of an accommodating state (Kerkvliet 2010), to a “meditation space” (Koh 2006). Newer perspectives on state-society relations in Southeast Asia aim to take an “approach from below” and understand the relationship as something dynamic and continuously negotiated (Berenschot et al. 2016). These perspectives aim to understand citizen rights and agency and provide an alternative understanding of modern authoritarianism in Southeast Asia as put forth by political scientists, such as Lee Morgenbesser’s (2020) theory on sophisticated authoritarianism. Similar discussions can be found in academic works on civil society in Vietnam (Thayer 2009; Wischermann 2010; Waibel et al. 2013).

Citizenship as a conceptual framework is thus used in recent academia in the Vietnamese context to understand how ordinary citizens demand accountability from the state in return for providing legitimacy and support (Nguyen Quang Dung 2020; Binh 2021). Obligations and rights on both sides, therefore, characterize state-society relations. This form of “cooperative citizenship” (Le and Nicolaisen 2021) is designed as an idealized form of state-society relations in which citizens and state institutions do not compete and negotiate over interests, resources, and needs but cooperate to modernize and reconstruct Vietnamese society for the creation of a better nation. A good citizen, according to this understanding, puts the common good of the nation before their interests and needs and is thus willing to make sacrifices for the future of society. Inherent in this perspective from the state’s point of view is that Vietnamese government institutions best know what constitutes the common good. Hence, the idea of cooperative citizenship is underscored by a normative dimension: the morality of caring. Putting the nation first, feeling an obligation to improve society, and supporting the state are not merely political demands but reframed as moral obligations. Nguyen-Thu Giang (2020) has written on this moral dimension of care work in the context of social expectation, particularly with regard to the role of women.

Politics and morality are deeply intertwined, as can be seen in political campaigns like the “Civilized Streets” campaign. Also, political messaging often has a moral aspect (Binh 2021). This morality dimension is discussed in academics, for example, by Susan Bayly (2020) in her work on state imagery in public spaces and moral citizenship in Vietnam. The morality of caring has a nationalist undertone, which references historical struggles and individual sacrifices to frame state demands, implying a moral obligation on the part of citizens to support the nation. Public willingness for individual sacrifice is communicated as inherited by previous generations and tied to what it means to be Vietnamese. This link between morality and care can be found also in community-level discourses on social responsibility, the role of women in society, and the obligation of children toward the elderly. However, when looking at citizenship in the Vietnamese context, it is necessary to distinguish between formal image and informal practices (Ehlert 2012). The expectation of “cooperative citizenship” is often translated into conflicted forms of citizenship that challenge the state’s perspective on state-society relations (Le and Nicolaisen 2021). However, within the framework of crisis response, as seen during the pandemic, the state needs to rely on social cooperation to achieve widespread social compliance, including people following rules and regulations (Glik 2007). Public communication can reduce instances of conflicted citizenship. In the context of the pandemic, the cooperation of citizens in preemptive measures was—and is—crucial for an effective response. Thus, a cooperative citizenship approach in public communication is a feasible strategy to mobilize society.

This paper argues that the ideal of “cooperative citizenship” became an important message to mobilize the public, gain legitimacy, maintain control, and thus create a cohesive Covid-19 response in Vietnam. We argue that the pandemic was broadly framed in terms of a “morality of caring” in order to increase the levels of mobilization and people’s engagement in the sense of cooperative citizenship. Thus, pandemic communication can help to provide insights into the construction of this cooperative citizenship narrative and the underlying symbols and arguments.

Background: Covid-19 in Vietnam

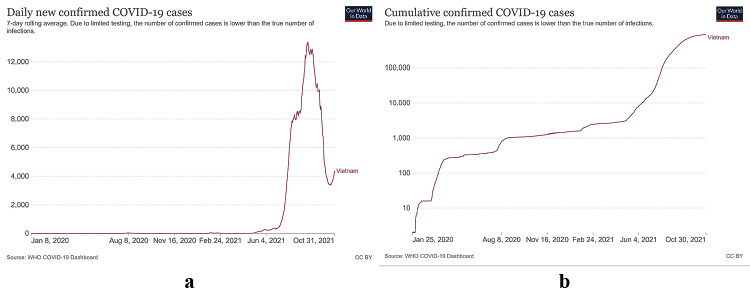

Vietnam’s declared goal from the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic was to wipe out the virus entirely. This zero-Covid strategy had its roots in Vietnam’s limited health infrastructure, its previous experience with other infectious diseases, and a general weariness on the part of the Vietnamese government with official information coming from the Chinese government (Le and Nicolaisen 2022). Accordingly, as early as January 16, 2020, the Vietnamese government ordered ministries and relevant agencies to take measures against the spread of pneumonia caused by the then still novel coronavirus (VNS 2020). Thus, when the first Covid-19 infection was registered in Vietnam on January 23, an immediate and broad political response was implemented, including the closing of all schools nationwide following the Tet holidays and canceling of all flights from China on February 1 (Murray and Pham 2020). This was followed by the closure of all borders to foreigners on March 22. The authorities dealt with isolated local breakouts by locking down villages, neighborhoods, and factories between February and July 2020 in order to contain the spread of the virus and trace each individual infection back to its source. Due to this decisive strategy, Vietnam was able to initially contain the spread of the virus, as shown in Fig. 1a on the development of daily Covid-19 cases. Fig. 1b shows the different waves of Covid-19 outbreaks in Vietnam.

Fig. 1 Development of Confirmed Covid-19 Cases from January 2020: (a) Daily New Confirmed Cases; (b) Cumulative Development of Cases on a Logarithmic Scale

Source: Mathieu et al. (various years)

Consequently, between mid-April and the end of July 2020 Vietnam had no community infections; it registered infections only inside quarantine camps, due to people arriving on repatriation flights. In the first half of 2020 the country had fewer than 450 infections and no Covid-related deaths (Mathieu et al., various years; Le Huu Nhat Minh et al. 2021).

The streak of low infections ended with an outbreak in Đà Nẵng that began on July 28, 2020, when—for the first time—some of the early infections could not be traced back to their original source. The outbreak occurred during the height of Vietnam’s travel season in a domestic tourist destination. A large number of people attempted to leave the region in order to escape a lockdown, which hampered efforts to isolate the outbreak regionally. On July 31, 2020, Vietnam registered its first Covid-19 death. Over the next month the country registered more than 600 new infections, more than in the entire first six months of the pandemic, and 32 deaths (Mathieu et al., various years). However, by the end of August the outbreak in Đà Nẵng was under control, with no new deaths from September 4, 2020 to May 2021 and no locally transmitted infections for almost three months. However, on November 28, 2020, a Vietnam Airlines crew member tested positive while violating government-mandated Covid-19 quarantine protocols and infected three other people. This led to the first new cluster in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) in 120 days (Tuoi Tre News 2020). The authorities responded with temporary measures in HCMC, including the lockdown of three residential neighborhoods, the closure of universities, and the cancellation of outdoor events. Due to these measures, the outbreak did not spread further and infections remained mostly under control until the end of January 2021 (Manh 2020).

The next outbreak, a third wave, occurred from January 28, 2021 to March 25, 2021, in Hai Duong, with the Alpha variant responsible for most infections. Within a time frame of two months Vietnam registered around 1,000 new cases, of which more than 900 were community transmitted. However, as most patients were young and healthy, there were no new deaths (Le Huu Nhat Minh et al. 2021; Le Tuyet-Anh T. et al. 2021).

Generally, while Vietnam registered three infection waves between February 2020 and April 2021, globally the country’s approach was discussed as a successful response to the pandemic by experts and in the media—especially given Vietnam’s limited financial resources and close geographic proximity to China (Dabla-Norris et al. 2020; Tran et al. 2020).

With the emergence of new virus variants and waves of community infections, from April 27, 2021 case numbers started to rise rapidly, particularly in HCMC and surrounding provinces (Le Thi Phuong 2020). This led to Vietnam’s worst wave up to that point, with 19,063 deaths and around 770,000 infections by the end of September (Mathieu et al., various years). The government imposed a lockdown from August to September 2021 in an effort to contain the outbreak, which led to economic difficulties.

Although vaccines became available in 2021, Vietnam faced supply issues due to a lack of government funds, an unequal global distribution with Western governments stockpiling most of the supply, and a societal distrust of Chinese-produced vaccines (Dao 2021).

However, with an increase in the vaccination rate by the end of 2021, when almost 80 percent of the population had received at least one dose, Vietnam ended its zero-Covid policy (Viet 2021).

Overall, by the end of 2021 a total of 1.7 million Vietnamese had been infected with Covid-19 and more than 32,000 people had died (Mathieu et al., various years). However, on a global scale Vietnam’s Covid-19 strategy can be perceived as having been comparatively successful due to its rapid and transparent approach in the early months (Le and Nicolaisen 2022).

Vietnam’s Pandemic Communication Strategy

One of the major arguments found in the literature on Vietnam’s response strategy focuses on the role of transparent and immediate communication by the authorities during the first year of the pandemic. Academics argue that transparent communication was responsible for broad social mobilization and increasing legitimacy for the Vietnamese government in this time frame. This corresponds with the academic literature on crisis communication. Deborah Glik (2007), for example, argues that the way people respond to hazards is determined not by the actual risk but by the perception of risk. Stephen Flusberg et al. (2018) explain the need for simple communication: when the amount of information becomes too complex, with daily changing regulations and rules, it can lead to resignation or numbness. Here, visual risk communication as seen in the use of propaganda posters and social posts can be understood as a means to reduce complexity.

Below, we will take a brief look at Vietnam’s pandemic communication strategies as summarized in the relevant literature.

As mentioned above, Bayly (2020) pointed out the limited effectiveness of propaganda posters in public spaces in a study in Hanoi as reported by her interviewees. Rather, her study pointed toward a negotiation process where Hanoi residents selectively engaged or disengaged with public messaging as their agency. Christophe Robert (2020) points toward a similar approach in his paper on the representation of Covid-19 in public spaces in Hanoi at the beginning of the pandemic. He also states that while propaganda posters were widely distributed, their effectiveness in influencing behavior might have been limited. He mentions instances of defiant behavior by residents, for example, ignoring mask mandates. He gives examples of how Covid regulations and lockdowns affected public spaces, for example, with lower traffic and the setting up of checkpoints. However, he also points out that in Vietnam often “the language and visualization of mobilization are prominent and prominently displayed, without the corresponding, actual mobilization” (Robert 2020, 7). Citizens in Vietnam often engage in tactical resistance in their media consumption and are critical of official messaging, because they are familiar with state tactics of obstruction and misinformation (Harms 2016, 109–110). This skepticism becomes increasingly relevant as social media has opened new arenas for negotiation that are often more difficult to censor (Pearson 2020).

Thus, looking at Covid-19 communication alone might not help in assessing the success or failure of Vietnam’s Covid-19 response. However, it offers valuable insights regarding the underlying narratives used to frame the pandemic and, ultimately, state-society relations in Vietnam from a government perspective.

Nguyen Hong Kong and Ho Tung Manh (2020, 10) and Bui Trang (2020) mention how, from the beginning, the Covid-19 pandemic in Vietnam was framed by war metaphors—a “language of war” and historical events. As the pandemic became the new enemy, slogans like “Every citizen is a soldier” (Nguyen Hong Vinh 2020) and “So long as there is a single invader left in our country, we have to wipe it all out” (Giao 2020) reappeared. The Party-state located the pandemic response in a long tradition of the “war against imperialism” extending beyond the Vietnam-US War (Kirubakaran 2020; Nguyen Maya 2020; Truong 2020; Hartley et al. 2021, 159).

In communication research, opinions about the effectiveness of war metaphors differ. War metaphors provide a structural framework to communicate abstract and complex situations and convey emotions. Historical points of reference can create meaning for the population. This could increase the understanding of the pandemic and its far-reaching consequences. Embedding the pandemic in the national memory and the trauma of war gave weight to the necessity of a unified and swift reaction: every citizen was needed, had sacrifices to make, and had a role to play, as in wartime. Such framing establishes emotional continuity (Flusberg et al. 2018). However, Flusberg et al. (2018) argue that continuous framing in martial language can have adverse effects. The reduction of moral complexities and emotional weight stokes social conflicts. Due to the focus on the need for sacrifice and state control, people unwilling to make sacrifices or accept state control are quickly singled out by the authorities. When a pandemic is understood as an existential crisis, self-righteous bullying and mobbing become acceptable (Flusberg et al. 2018).

As stated by Nguyen-Thu (2020, 2), the communication strategy of the Vietnamese state during the first year of the pandemic moved beyond the aim of social mobilization to increase government legitimacy with messages of hope, order, and control often set against Western failure. In particular, in the early months of the pandemic from March to May 2020, the official communication was characterized by transparency with the aim of signaling the severity of the crisis but also reassuring the public of the government’s capacity to deal with it. The authorities shared the newest data, photos, and videos to fight rumors and uncertainties, which led to a high degree of engagement on social media. A study by Nguyen and Ho (2020) analyzing the level of transparency, amount of (daily) information, and wide range of communication channels used by the authorities in the first months of the pandemic from March to May 2020 confirms this effort to address and refute rumors and misinformation.

The increasing use of social and online media to communicate shows a general shift in Vietnamese politics toward embracing digital technology as a political tool. On February 8, 2020, for example, the Ministry of Health launched the Vietnam Health website. Less than one month after the first Covid-19 case was detected in Vietnam, on February 14, 2020, citizens were asked to download the new official mobile phone app Sức Khỏe Việt Nam (Vietnam Health) to access information regarding the pandemic. This app was followed by several other mobile applications: NCOVI, Bluezone, the Vietnam Health Declaration app, and Hanoi Smart City. While the apps served different functions, they were all used to convey information to the public and also to gather information for mitigating the spread of Covid-19. The information collected included individuals’ travel history and health status, including Covid-19 symptoms.

Overall, the communication strategy included a highly diverse set of tactics—from loudspeakers and door-to-door warnings to neighborhood watches and social media engagement. Interestingly, as emphasized by Nguyen-Thu (2020), the official communication strategy combined the use of the old public speaker system—a relic of the Vietnam War, nowadays seen mostly as a community annoyance—with the widespread use of social media, particularly apps and Facebook. This made information accessible and available to everyone. As in the case of propaganda posters, new digital technologies were embedded in the conservative legacy of the Communist Party. This created a dichotomy between wanting to alert the public regarding the severity of the situation and the need for control. However, as Nguyen and Ho (2020) state, the use of public loudspeakers also allowed for better reach in more rural communities with less access to digital technologies. Increasing the reach of state messaging thus also influenced the choice of communication channels. Numerous awareness campaigns (Nguyen and Ho 2020) also aimed to mobilize residents and reduce the level of disengagement described by Robert (2020) above. These campaigns included music challenges and cooperation, poster design competitions, and social media engagement.

Nguyen-Thu (2020) points to studies on digital networking (Phuong 2017), popular music (Hoang 2020), and popular television (Nguyen-Thu 2019) that show public spaces can serve as sites of contestation and negotiation with the authorities and allow for gray areas to address local grievances. This points toward the role of communication in negotiating citizenship in Vietnam.

Methodology

This section contains a visual analysis of the construction of cooperative citizenship in Covid-19 communication from state actors. This paper looks at different instances of public communication in the form of images and videos published and circulated by the Vietnamese government from the beginning of the pandemic until August 2020, with a geographic focus on the three largest cities: Hanoi, HCMC, and Đà Nẵng.

The focus will be on the visual and verbal framing of the pandemic in public communication materials from government sources. The paper follows a qualitative content analysis approach, building on existing research on the role of visual communication material in state-society relations, as proposed by researchers such as Bayly (2020) for Vietnam, Tom Walsh (2022) for the Middle East, and Joanna Sleigh et al. (2021) for social media.

To this end, we collected visual data on Covid-19 messages online, particularly from newspapers and government websites. This data was then separated into two categories: propaganda posters, for which we used photographic evidence that these posters were distributed in public spaces; and social media messaging, particularly music videos. For the music videos, we used videos distributed by the official YouTube channel of the Ministry of Health, as we concluded that the messaging in these videos would be closely aligned with the government’s messaging strategy. We used number of views and likes as measuring sticks to focus on those videos with the broadest public appeal.

By comparing offline messaging (propaganda posters) with online messaging (videos), we aimed to address one problem with propaganda posters that has been raised in research on Vietnam. Bayly (2020) and Robert (2020) point to the passive character of propaganda posters, which allows social actors to disengage or ignore the messaging. Consequently, propaganda posters to some degree represent the colonization of public spaces by state ideology. Conversely, social media messaging allows for a voluntary engagement with content as those watching music videos in the framework of the pandemic choose to engage with the topic.

By analyzing the visual content in combination with the text included in the two categories of data, we aimed to identify underlying categories of messaging that were employed to appeal to the public: (1) the female gaze, (2) patriotism, (3) social responsibility, (4) gratitude, and (5) simple messaging.

From this visual analysis of common tropes and narratives, the paper aims to reconstruct the government’s perspective on citizenship in Vietnam, starting with this framework of cooperative citizenship. The aim is to better understand the underlying dimensions of the cooperative citizenship ideal.

Case Study: Direct State Messaging as Covid-19 Communication: Propaganda Posters in Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, and Đà Nẵng

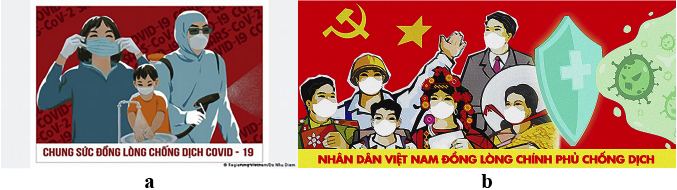

As a starting point for the analysis of the framing of the Covid-19 pandemic in Vietnam, we will look at the most used propaganda posters displayed in public spaces in HCMC and Hanoi during the first stage of the pandemic in spring 2020. These images were displayed along major streets and alleyways, on the sides of trucks, and as smaller posters on school gates. They were sometimes single displays, and in one case they combined a large display of the relevant regulations in the common state design of white script on red ground. These propaganda posters represented the primary state messaging with typical socialist state iconography that pervades public spaces in everyday life in Vietnam. They presented a simplification but also a preserving way of communicating, connecting public spaces with private (Bayly 2020). Besides posters (as seen in Fig. 2a), state messaging was included also in numerous murals in urban public spaces and distributed in neighborhoods and directly to households at the ward level by local officials. However, the following analysis will focus only on the framing and narrative of posters (as seen in Fig. 2b) and not on their distribution.

Fig. 2 Covid-19 Messaging Dominates Urban Public Spaces as Wall Murals and Propaganda Posters

Sources: (a) AFP and Asia News Network (2021); (b) VNA (2020a)

The Female Gaze

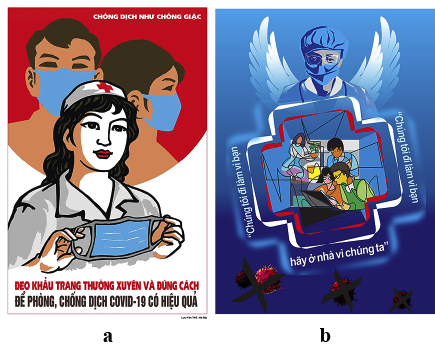

The poster in Fig. 3a is dominated by the profile of a woman’s face with a mask next to the text “COVID-19 pandemic prevention is to protect yourself, your family, and society” (Phòng, chống đại dịch Covid-19 là bảo vệ chính bạn gia đình và xã hội) on a red background, with only the text and woman in white and light yellow. Red is commonly used in state propaganda and official public signs. It is linked to the state flag, the revolution, and the Communist Party and thus has a strong link to national identity and the state. The face of the woman is dominated by the mask and the eyes, which seem to look at and address those passing by. The picture of a woman with a mask is not new on propaganda posters. It was used pre-Covid on posters advising the use of face masks and body covers to protect against dust, fumes, and the sun while riding a motorbike. As stated by Robert (2020, 4), the poster employs performative speech, figurative images, and the lack of a subject. Thus, the woman in the poster “becomes a figure representing a segment of the population” (Robert 2020, 4), or even “the People.”

The poster in Fig. 3b also displays a woman looking at passersby. However, the iconography differs in color and style. This poster displays the photo of a female medic in scrubs with a face mask and protective headgear above the text “Use a mask regularly and properly wash your hands to prevent the spread of COVID-19” (Sử dụng khẩu trang thường xuyên rửa tay đúng cách để phòng chống để dịch Covid-19). The main color of the image is blue, with only the last part of the text in red. This blue coloring references the protective uniforms of medical workers and other workers in protective gear fighting Covid-19. The poster has a pedagogic image of handwashing, which was used also in previous public health campaigns by the government and international NGOs (Robert 2020, 4). Overall, the message of the poster relies on the friendly yet firm professional authority of the medical professional to advise the public.

Both posters in Fig. 3 play on the mental connection between caring (for a family and society) and the often-conceived role of women as caregivers. This might play into what Bayly (2020) describes as the “highly gendered nature of its imagery” in socialist iconography. It points toward a social responsibility not only to oneself but also to the family and society to follow preventive measures, thus creating a moral framework overseen by everyone in public. This is underlined by the direct stare of the women on the posters watching passersby, which is intensified because the rest of the women’s faces is hidden behind the face masks, putting the focus on the eyes.

Patriotic Fight and Heroism

Many of the propaganda posters rely on patriotic messaging, which aims to create historical continuity with a link to the anti-imperialist and socialist struggles for independence.

Fig. 4a shows a small boy with a face mask washing his hands in front of a glove-wearing female medic in scrubs putting on a face mask, along with a person in protective gear (overall, glasses, and mask) working to disinfect public spaces. The background is dark red, with “Covid-19” repeatedly written on it. The message below (red letters on a white background) reads “Let’s join hands to fight against Covid-19” (Chung sức đồng lòng chống dịch Covid-19).

Fig. 4 Patriotic Messaging and War Rhetoric in Covid-19 Communication

Fig. 4b shows a group representing the Vietnamese people, including a soldier, a schoolchild, a worker, a female farmer, and an ethnic minority woman, all wearing masks. Above, a man in a suit stands over the assembled group, probably symbolizing the Vietnamese government. The text below states “Vietnamese people agree with the government to fight the epidemic” (Nhân dân Việt Nam đồng lòng chính phủ chống dịch). The background is red, with the yellow star from the Vietnamese flag and the socialist symbol of the hammer and sickle in the top left corner. On the right, a light blue shield with a cross protects the group from the attacking coronavirus.

In the poster in Fig. 5a, designed by the artist Luu Yen The (Humphrey 2020), the central figure is a traditionally clad nurse (with headgear and a white dress) advising on proper Covid-19 prevention. This poster could also be seen as a mural in HCMC in 2020. The text reads “Wear a mask regularly and properly to effectively prevent and control the Covid-19 epidemic” (đeo khẩu trang thường xuyên và đúng cách để phòng, chống dịch covid 19 có hiệu quả). In the front, a nurse with long hair holds a blue mask, while in the red background are a man and a woman wearing masks. In smaller letters on top, the poster reads “Fighting the epidemic is like fighting against the enemy” (Chống dịch như chống giặc).

Fig. 5 The Role of Health-care Workers as National Heroes

Sources: (a) Communist Party of Vietnam Online Newspaper (2020); (b) Trung tâm Thông tin Triển lãm Thành phố HCM (2020)

The poster in Fig. 5b was part of a global health-care sector campaign in 2020. The campaign used photos of health-care workers under the slogan “We go to work for you; please stay home for us” to motivate people to shelter in place. The example here shows a tired-looking health-care professional with angel wings in scrubs, mask, and headgear looking over a group of people framed by a medical cross with red and white outlines and the same slogan. The cross seemingly provides a protective shield against the coronavirus displayed at the bottom of the poster. The poster creates a narrative of heroism, sacrifice, and a national fight against an external threat.

In all four posters (Figs. 4, 5), the community of the Vietnamese nation is asked to fight the pandemic. As the poster in Fig. 4b shows, this community is inclusive with regard to ethnicity, gender, and social class. The posters define the fight as washing hands, wearing masks, and staying home. Nationalist undertones can be found in all four posters, including the common use of nationalist symbols like the flag, the color red, and the messaging in the slogans. In this regard the poster in Fig. 4b is the most obvious, directly referencing unity with the government and the socialist symbol of the hammer and sickle. The poster in Fig. 5a combines the red with a slogan that directly references the coronavirus as the enemy and compares the fight against the pandemic with a war, thus falling back on the use of war rhetoric also used in some public speeches from the government in early 2020. In contrast, the poster in Fig. 5b more directly points toward the sacrifice of the fight and also connects Vietnam to the international community in its fight.

Overall, the messaging underscores the conclusions of Nguyen-Thu (2020), who points toward the use of wartime metaphors in pandemic communication as a means to highlight the severity of the situation but also the need for solidarity, social responsibility, and national unity. With the aim of increasing state legitimacy, besides increased transparency, the narrative framing of the pandemic becomes relevant.

Taking Care, Taking Responsibility

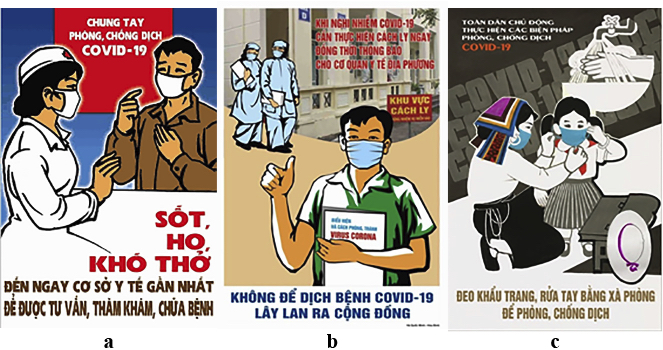

The posters in Fig. 6 center on the provision of advice with iconography embedded in storytelling. Overall, the style is reminiscent of more classic propaganda iconography from the 1950s and 1960s.

Fig. 6 Health-care and Preventive Measures against Covid-19

Sources: (a, b) Trung tâm Thông tin Triển lãm Thành phố HCM (2020); (c) Công an Nhân dân Online (2020)

In the poster in Fig. 6a, a man wearing a brown shirt and a face mask points to his chest while consulting a traditionally dressed female nurse with a face mask, white dress, and headgear. The top of the poster has a blue background with a red box in the top middle reading “Join hands to prevent and fight the Covid-19 pandemic” (Chung tay phòng, chống đại dịch Covid-19) in white block letters. The bottom half is dominated by white, with the outline of the nurse’s dress and the text “Fever, cough, difficulty breathing” (Sốt, ho, khó thở) in red and a little smaller in brown “Go to the nearest medical facility immediately for advice, medical examination and treatment” (Đến ngay cơ sở y tế gần nhất để được tư vấn, thăm khám chữa bệnh). In the second poster of this set (Fig. 6b), a man with a face mask in a green shirt holds a brochure on preventive measures against Covid-19. In the background, two doctors/nurses with more traditional scrubs and face masks walk in front of the photo of a quarantine area. On top, the text states “When suspected of being infected with Covid-19, it is necessary to immediately isolate and notify the local health authority” (Khi nghi nhiễm Covid-19 cần thực hiện cách ly ngay đồng thời thông báo cho cơ quan y tế địa phơng).

In the poster in Fig. 6c, an ethnic Thái woman kneels in front of a little girl in a school uniform and helps her to put on a face mask, next to a small stool with a sun hat and an old-school leather schoolbag. Except for the red word “Covid-19,” the colorful head covering of the Thái woman, the blue mask, and the red neckcloth of the school uniform, the poster is in black and white. At the top, there is again the picture of handwashing practices in white on a dark background. The poster states, “The whole population actively implements measures to prevent and control the epidemic” (Toàn dân chủ động thực hiện các biện pháp phòng, chống dịch); and at the bottom is the text “Wear a mask, wash your hands with soap to prevent the epidemic” (đeo khẩu trang, rửa tay bằng xà phòng để phòng chống dịch).

The posters in Fig. 6 link the narrative of a united, national fight against the pandemic to a set of concrete instructions, particularly the need for medical help and quarantining when infected. As before, the choice of slogans points toward martial rhetoric that looks for broad mobilization against the pandemic. Again, the pandemic is framed as an external threat to the nation.

In the first two posters (Figs. 6a, 6b), the focus is on medical professionals as providers of support and information. The third poster (Fig. 6c) includes the mother as a familial caregiver in a similar role, responsible for her family following the rules and implementing preventive measures. Using the image of a woman from an ethnic minority underlines the sense of national unity, urgency, and a “community of fate” (Baehr 2005) fighting together, which includes every family and person regardless of socioeconomic background. Overall, taking care of oneself and one’s family and following instructions are depicted as a national responsibility and thus gain a moral dimension.

Finally, the iconography of medical personnel is found in several images on Covid-19 messaging. However, in other images the medical professional is mostly seen in modern blue scrubs. In Fig. 6a the nurse and man seem to be placed in a less modern context, providing iconographic continuity to the past and creating a sense of nostalgia and timelessness.

Simple Messaging

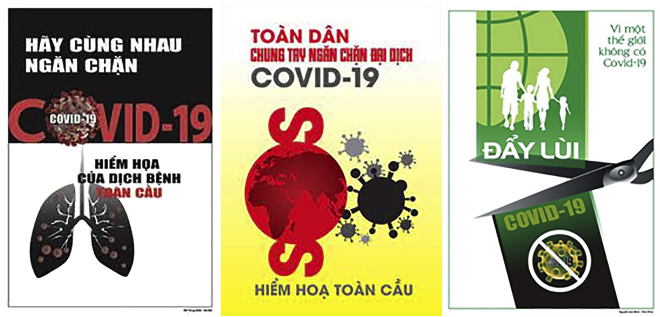

A final grouping of propaganda posters (Fig. 7) combines a slogan with primary colors (as did most other posters) and a simple graphic into a very basic corporate design style. The most prominent poster, which was displayed on streets in Hanoi and HCMC, shows a pair of black lungs infected by the coronavirus on a white background. Against the black background on top, the white text reads “Let’s prevent it together” (hãy cùng nhau ngăn chặn) above the word “Covid-19” in large red letters with a symbolic coronavirus as “O.” Below, the poster states “The dangers of a global epidemic” (Hiểm họa của dịch bệnh toàn cầu) with the last two words also in red. The poster creates a sense of threat, imminence, and uncertainty. From this sense of threat, the poster calls for unity in fighting the pandemic. It also points toward the global nature of the threat. The message of a global threat is conveyed also in the second poster. The center of the poster shows a globe next to some stylized coronaviruses on a sickly yellow background. The globe is used to spell the word “SOS.” The slogan on the poster states “All people join hands to prevent the global threat of Covid-19 pandemic” (Toàn dân chung tay ngăn chặn đại dịch Covid-19 hiểm họa toàn cầu), with the first half of the words in red. In both posters, the health risk is also prominently displayed. Contrary to the menacing tone of the first two posters, the third poster combines green and white and focuses on a message of hope—“For a world without Covid-19 – Repel Covid-19” (Vì một thế giới không có Covid-19 – đẩy lùi Covid-19)—with a pair of scissors cutting the word “Covid-19” from a green ribbon in the center of the poster below the silhouette of a family in front of a stylized globe.

Fig. 7 Simple Information Posters on Covid-19

Source: Trung tâm Thông tin Triển lãm Thành phố HCM (2020)

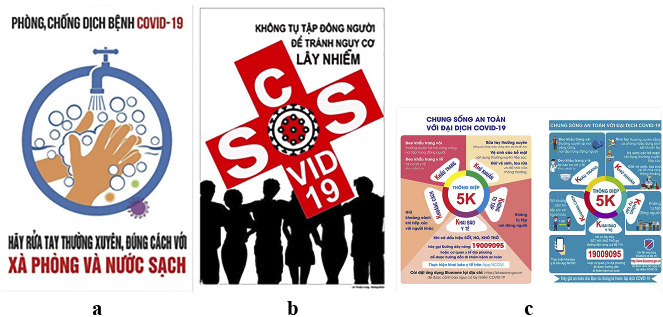

Simplified messaging, simple, abstract graphics, and primary colors, particularly red, were used also in some of the informative posters and communication materials (Fig. 8) distributed in neighborhoods, sometimes directly to households. These included posters on handwashing, social distancing—“Do not gather in large numbers to avoid the risk of infection” (Không tụ tập đông người để tránh nguy cơ lây nhiễm)—and the “5K” rules: (1) face mask (khẩu trang), (2) disinfection (khử khuẩn), (3) not gathering in groups (không tụ tập), (4) medical checkup (khám bảo y tế), and (5) distancing (khoảng cách). The 5K poster in Fig. 8c exemplifies a whole set of similar posters, which often contained additional text to explain the relevant rules depending on location and local needs.

Fig. 8 Preventive Information against Covid-19

Sources: (a, b) Trung tâm Thông tin Triển lãm Thành phố HCM (2020); (c) Huyện (2021)

Social Engagement: Poster Design Competition, Đà Nẵng, August 2020

As stated by Robert (2020), most propaganda posters in Vietnam dominate public spaces visually, but due to their omnipresence they often become invisible. Engagement or disengagement becomes a choice, as shown by research by Bayly (2020) for Hanoi. Propaganda posters thus become a tool to visually colonize public spaces by reducing the space for alternative messages and visual materiality.

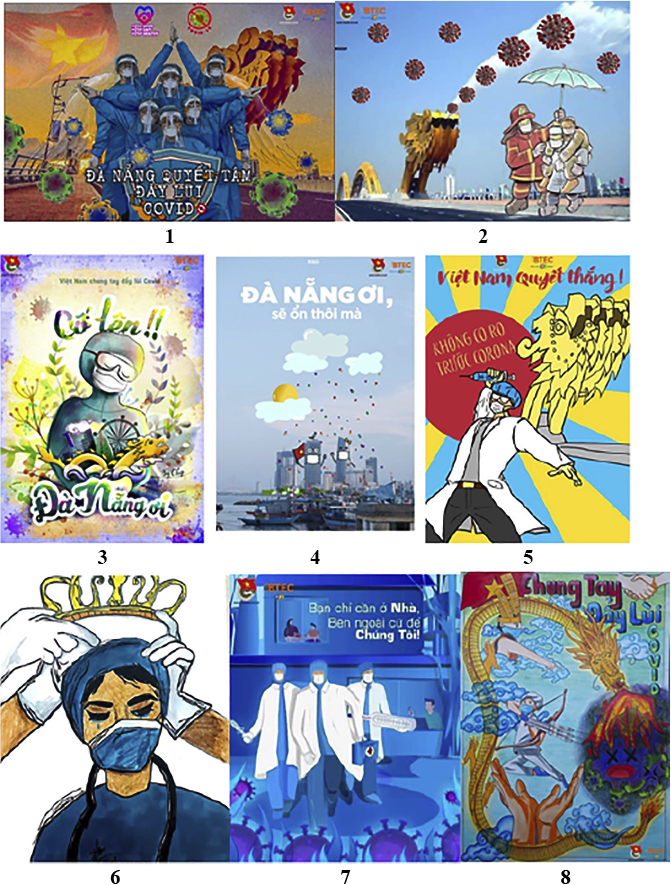

Some of the posters in Fig. 9 came from artist initiatives (see, for example, Humphrey 2020). However, beyond the visual colonization of public spaces and the visual framing of the pandemic, local authorities also aimed to engage the public more directly in the framing process in order to improve compliance and understanding, often in the form of competitions organized by companies—such as the Biti’s Hunter shoe design competition (Biti’s Hunter 2020)—local authorities, newspapers, and schools (Nguyen and Ho 2020). Below, we will discuss some of the posters created in a local poster design competition during the outbreak in Đà Nẵng in August 2020 (Khánh 2020; Xuân 2020). The competition, titled “Join Hands to Repel Covid-19,” was organized by An Khe ward (Thanh Khe District) and BTEC FPT International College in the Bao Đà Nẵng newspaper in mid-August and on the home page of the City of Đà Nẵng authorities: “Every citizen is a soldier, each picture and photo is a powerful spiritual weapon in the ‘great war’ against the Covid-19 epidemic. Let’s create beautiful and meaningful works with the Vietnamese people to fight against Covid”1) (Khánh 2020).

Fig. 9 Images from the Đà Nẵng Poster Design Competition, August 2020

Sources: Pictures 2, 6–8, Khánh (2020); pictures 1, 3–5, Xuân (2020)

Visual materials are used as tools for mobilization, to engage the public, and posters were an important part of the fight against Covid-19. Compared with official propaganda posters, the posters from the competition, which also included images created by children, were less direct in their messaging and choice of color and motive. However, as seen in the selection of posters in Fig. 9, the majority depict health-care and emergency workers as well as local landmarks, particularly the Dragon Bridge. One image depicts the skyline of Đà Nẵng instead, with two skyscrapers wearing masks in front of a clear morning sky, providing a picture of hope. Another poster uses a stylized version of six doctors forming a star in front of the Dragon Bridge and a Vietnamese flag. The image of health-care workers as heroes, protectors, and caretakers is seen in numerous posters. In one, a crying female doctor is given a crown. In another, a female doctor painted in soft aquarelle colors carries a golden baby dragon together with the city of Đà Nẵng. In two other posters, doctors employ syringes as weapons against the attacking virus. One of the posters references the founding mythology of Vietnam. Overall, the local identity is more prominent than the national. Common motives beyond locality are the heroism of emergency and health-care workers along with their sacrifice, fighting, and caring as well as a sense of local solidarity and comfort in local resilience rooted in personal experience. From this, the call to fight together can gain some meaning. This provides a more personal framing of the pandemic compared with official posters.

Case Study: Indirect Messaging and Mobilization: (Music) Videos and Social Media Campaigns

As part of its official communication strategy, the Vietnamese Ministry of Health (MoH) regularly publishes videos on its official YouTube channel and has cooperated with artists in producing songs related to the pandemic. Under the playlist “Activities to respond to the COVID-19 epidemic” (Các hoạt động hưởng ứng phòng chống dịch Covid-19) there were a total of 48 videos uploaded as of June 12, 2022.

In order to demonstrate the important role played by music videos in Vietnam’s Covid-19 response, the case of one of the first corona-related songs going viral will be briefly outlined here. On March 31, 2020, a music video titled “Jealous Coronavirus” (Ghen Cô Vy) was uploaded to the MoH YouTube channel. The song was produced by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health in cooperation with the singer Khắc Hưng (Saigoneer 2020). The video combines a cartoon-like animation style and catchy music with an educational function. The lyrics and animations explain how to wash one’s hands properly, stress the importance of wearing a mask, and urge people to avoid crowded places. The original video was uploaded to YouTube on February 23, 2020 on the official channel of the singer Min (Min Official 2020) and was shared by global media outlets such as Last Week Tonight with John Oliver on HBO, becoming an instant hit globally. It has since inspired a viral TikTok dance trend in Vietnam (La et al. 2020, 12–14; LastWeek Tonight 2020). As of July 2022, the video had been watched more than 110 million times. Interestingly, however, the views of the song on the official MoH channel were fewer than 10,000 as of July 2022.

While the song’s popularity abroad can be credited to the catchy soundtrack and lighthearted approach to explaining pandemic measures, its popularity in Vietnam can be explained by the song’s reference to the Vietnamese community and its employment of nationalistic narratives. As seen in the discussions on the posters above, these are common themes and topics in the government’s communication strategy. One concrete example from the “Jealous Coronavirus” song is the reference to China. Following the song’s global success, new versions of it were uploaded to the official MoH YouTube channel. The first one was an English-language version on April 24, 2020 (Vietnam, Bộ Y tế 2020d). In the early versions of the song, the lyrics refer to the virus as originating from Wuhan: “My hometown is Wuhan” (Quê của em ở Vũ Hán). On March 24, 2020, a cover of the song in the Chinese language with Vietnamese subtitles was published on a private channel, which also used the line “It comes from Wuhan” (Ta shi laizi Wuhan 它是来自武汉) (Chinese Home 2020). While the first outbreak was detected in Wuhan, this focus on China played on existing anti-Chinese sentiments and anti-China nationalism in Vietnamese society (Vu 2014). On May 28, 2020, the MoH uploaded versions of the song with subtitles in several ethnic minority languages of Vietnam (Tày, Thái, Cao Lan, Dao, H’mông, and Sán Chỉ) as well as sign language. In these versions, the lyrics were changed to say “Over the past few days, I have created many waves” (Bao ngày qua, em tạo ra bao sóng gió).

Several music videos uploaded during the early waves of the pandemic in Vietnam, between February and late August 2020, are now analyzed with regard to their style and central message. Based on this analysis, these videos can be categorized into (1) videos showing gratitude, for example, to health sector workers or government institutions, such as the MoH; (2) videos referencing patriotism and using war rhetoric to call on people to fight the virus; and (3) videos urging the public to cooperate and adhere to pandemic measures as well as educating them regarding proper conduct.

Gratitude

On April 16, 2020, the MoH uploaded a music video titled “Thank You” (Vietnam, Bộ Y tế 2020b). The video shows famous Vietnamese singers giving thanks to health-care professionals. The video begins with a compilation of clips from Vietnamese news shows, with images from hospitals, WHO press conferences, and test centers. They are shown in quick succession, accompanied by driving music, creating a dramatic effect and a serious, almost alarming atmosphere (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10 MV “Thank you: Những chiến binh thầm lặng” do Bộ Y tế phối hợp với Gala nhạc Việt thực hiện (“Thank you: Silent warriors” performed by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with the Vietnamese Music Gala)

Source: Vietnam, Bộ Y tế (2020b)

The actual song begins with a soft piano tune in the background with clips of singers and musicians sharing sentiments of gratitude toward medical personnel for their “sacrifices” (Fig. 11). The lyrics describe these sacrifices with lines such as “deep lines under the cheeks” (từng vệt hằn sâu dưới má) and “swollen fingers” (những ngón tay đang sưng phồng). The song also refers to blue hazmat suits as “fragile blue armor” (chiếc áo giáp mong manh màu xanh), which is in line with the war rhetoric found in other pandemic songs and on propaganda posters.

Fig. 11 MV “Thank you: Những chiến binh thầm lặng” do Bộ Y tế phối hợp với Gala nhạc Việt thực hiện (“Thank you: Silent warriors” performed by the MoH in collaboration with the Vietnamese Music Gala)

Source: Vietnam, Bộ Y tế (2020b)

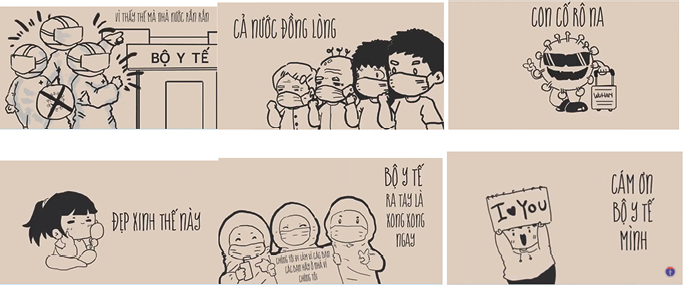

Two days later, the MoH uploaded the video “Thank You to My/Our Ministry of Health” (Cảm ơn Bộ Y tế mình) by the YouTuber Trang Hý (Vietnam, Bộ Y tế 2020c). According to the video description, the song is a funny cover of the song “This Spring Day Is Full of Prosperity” (Ngày xuân long phụng xum vầy), with lyrics adapted to the pandemic. The song is about giving thanks to the MoH, with lines such as “Thank you to my/our Ministry of Health for always doing its best and making sacrifices to save us” (Cám ơn bộ y tế mình đã luôn hết mình và cố gắng hy sinh để cứu tụi em). The singing voice has been digitally altered to be higher pitched and sped up, resulting in a voice effect similar to cartoon characters that seems childlike and underlines the entertaining function of the song. The lyrics also include comedic lines, such as “[I am] so beautiful but [I] have to stay at home because [I am] scared of corona” (đẹp xinh thế này mà phải ở trong nhà vì sợ cố rồ na). Furthermore, the song encourages national solidarity, as demonstrated by the line “The whole country unites to fight the monster together” (Cả nước đồng lòng cùng chống con quái vật). The music video is animated and simplistic, with black-and-white cartoon drawings of the coronavirus, health workers, and ordinary Vietnamese citizens. The drawings are humorous, with the virus depicted wearing sunglasses and carrying a suitcase with the word “Wuhan” on it (time stamp 00:20), again playing on anti-China nationalism (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12 Cảm ơn Bộ Y tế mình – Trang Hý (Thank you to my/our Ministry of Health – Trang Hý)

Source: Vietnam, Bộ Y tế (2020c)

The combination of a humorous and childlike messaging style with a political message demonstrates the creativity and adaptability of the Vietnamese authorities in communicating with the public. The efforts in creating music videos that resonate especially with a young population show the government’s view of public cooperation as important for a successful pandemic response and its recognition of the importance of communication for mobilizing public support. By involving famous singers and public figures, the MoH increased the likelihood of a favorable public response to the videos and the general Covid-19 response. The important role of public opinion in state legitimacy in the Vietnamese context has been described by Marie Gibert and Juliette Segard (2015) as “negotiated authoritarianism.” By creating and sharing videos showing gratitude to health workers and government institutions, the MoH aimed to demonstrate the government’s essential role in combating the pandemic and protecting Vietnamese citizens. The central message was that the government was fulfilling its obligations toward its citizens, which links back to the idea of “cooperative citizenship” (Le and Nicolaisen 2021). This message was supported by the images and lyrics referring to the emotional and physical sacrifices made by health sector workers, which may be interpreted as representing both the state’s efforts as well as sacrifices on an individual level.

Patriotic Fight and Heroism

Similar to the notion of sacrifice, the state also invoked nationalist and historical narratives of patriotism and heroism. One example was the song “Be Confident, Vietnam” (Vững tin Việt Nam), sung by Phạm Minh Thành and Hà Lê, which was uploaded on August 24, 2020 (Vietnam, Bộ Y tế 2020e). According to the video description, this is the theme song of the communication campaign “Confidence in Victory” (Niềm tin chiến thắng). This campaign was launched in early August 2020 by the MoH in collaboration with the United Nations Development Programme and aimed to encourage all members of Vietnamese society to support the government’s pandemic response (VNNews 2020a). The video was released on several media channels, such as Facebook, TikTok, and Spotify. The description encourages people to join hands in this “period of ‘resistance’ against this epidemic” (giai đoạn “kháng chiến” chống dịch này). Minister of Health Nguyễn Thanh Long was quoted in a newspaper article related to the campaign saying, “Every citizen, be a soldier on the pandemic prevention and control front. Unite, together we will conquer this plague” (VNNews 2020a), which again reinforces the image of Vietnamese citizens as soldiers and the pandemic as a war.

The music video shows scenes of daily life during the pandemic in Vietnam, such as a young girl going to school and people going about their daily activities wearing masks (Fig. 13). It uses these everyday scenes to demonstrate regulations, such as keeping a distance of two meters from others when standing in line or greeting one another without shaking hands. Beyond that, it also shows acts of kindness between community members. The video has a story arc related to a nurse and her father. In the beginning, the father is shown attempting to reach his daughter, who is busy working at the hospital. He is seen crossing off on a calendar the days he has not been able to see her. The video ends with the father and daughter reuniting at home. The atmosphere of the video is lighthearted, with a “youthful and modern melody” (VNS 2020) and people smiling and dancing throughout. The video also stars local celebrities, such as the football player Bùi Tiến Dũng. Like the videos discussed above, this song combines a lighthearted atmosphere with references to public solidarity, educational aspects, and public figures to create a motivational message.

References in the video to Vietnamese national identity are made by showing images of the Hanoi Ceramic Mosaic Mural, which, among other things, depicts historical events and legends (Mosaic Marble 2018). For example, there is an image of two soldiers with the Vietnamese flag in the background (time stamp 2:09) and the lettering “Quyet Thang,” meaning “to set one’s mind on victory” or “to be determined to win” (time stamp 2:11) (Fig. 14). These images link back to previous anti-imperial wars against France and the United States and are similar to the war rhetoric and images used on propaganda posters. The lyrics include references to solidarity (đoàn kết) and the inclusion of all citizens in the government’s pandemic response with the line “No one will be left behind” (sẽ chẳng để ai, bỏ lại phía sau). The country’s history is also referenced, focusing on the nation’s resilience in the line “With more than 4,000 years of history, the descendants of Lac Hong are still here” (Hơn 4000 năm lịch sử, con cháu Lạc Hồng vẫn còn đây). War rhetoric in the lyrics includes mention of the “decisive victory of our army” (quyết chiến quyết thắng của quân ta) and the line “singing over the sound of bombs” (tiếng hát át tiếng bom). By invoking Vietnamese history and previous struggles and framing the pandemic as a war, the song’s creators aimed to mobilize Vietnamese citizens to participate in the government’s Covid-19 response. Comparing current struggles to the sacrifices made by soldiers during war also put lockdown and quarantine measures into perspective.

Taking Care, Taking Responsibility

Beyond demonstrating the sacrifices made by the government and mobilizing the public through war rhetoric, the MoH also references a “morality of caring.” Caring in this context means the government taking care of its citizens, especially infected patients, and the state fulfilling its role as an educator, explaining to the public how they can protect themselves from the virus. On April 13, 2020, the MoH uploaded a song titled “Goodbye Covid” (Tiễn Covid), sung by Lê Thiện Hiếu (Vietnam, Bộ Y tế 2020a). The lyrics are predominantly educational, reminding people that “Masks are needed every day” (khẩu trang là thứ cần có mỗi ngày) and asking them to “always wash hands to avoid spreading [the virus]” (luôn rửa tay để tránh cô lây lan). Furthermore, the song calls on citizens to support the government’s response: “do not loiter [around with large groups of people]” (đừng la cà) and “please sit still” (xin hãy ngồi yên), meaning stay at home. The song is an easygoing pop song with some reggae elements and a catchy melody. The video style is animated and colorful. The images closely follow the song lyrics, showing different members of society wearing masks and health workers examining patients. The video portrays regular Vietnamese citizens from all strata of society as well as various workers involved in the pandemic efforts, such as soldiers and doctors. In this way, the video creators appeal to all sections of society, which helps to foster a sense of solidarity, inclusion, and individual responsibility in the community.

The video references popular shared images of corona patients being handed a bouquet of flowers after being released from hospital (SGGP 2020) (time stamp 2:58–3:03) (Fig. 15). This image is part of the story arc of the video, which shows people meeting each other on the streets, getting infected, visiting the doctor, and then recovering from the illness. The video storyline is educational and easy to understand. It portrays the comprehensive and initially successful government response to the virus. Thus, the video aims to create a positive public perception of the government and strengthen its legitimacy as well as public compliance. The images and tone of the video provide viewers with hope and motivation while simultaneously demonstrating that there is a real risk of community infection if regulations are ignored.

The video also references the MoH’s comprehensive information strategy. It shows images of cell phone messages being sent out to the public. The lyrics include the following line: “The Ministry of Health reminds everyone via media channels, does not miss anyone” (Bộ Y Tế, báo đài nhắc nhở không bỏ sót ai)—that is, it aims to reach everyone. This narrative again portrays the Vietnamese government as responsible, going above and beyond to keep the public informed and take care of its citizens. The video’s final image shows the then president of Vietnam, Nguyễn Xuân Phúc, being cheered on by supporters waving the Vietnamese flag (Fig. 16).

Social Engagement: Local Artists Spreading the Message

In line with the argument on “cooperative citizenship,” Vietnamese public figures embraced and adopted the state’s message of sacrifice and nationalistic narrative. This is evident from the large number of pandemic songs produced by local artists echoing the state’s sentiments and using similar language and imagery. One of the first of these songs was released on February 2, 2020, at a time when there were only 16 Covid-19 infections in the entire country. Although the song had a limited reach, with under 8,000 views on YouTube, its early publication shows the seriousness and urgency with which the Vietnamese government viewed the new Covid-19 virus. The song is called “Eyes of nCoV” (Đôi mắt nCoV) and is performed by the singer Sa Huỳnh (Sa Huỳnh Nhạc Sĩ Official 2020). The song’s main message is the sacrifices made by health-care professionals and the toll their work takes on their bodies and lives, as demonstrated by images of wrinkled hands and hair loss in the music video. Health professionals wearing full protective gear are shown working in the hospital, walking beside patients lying in gurneys, or resting on hospital floors. The video mixes black and white with color images. The tempo of the singing increases throughout the video, creating an urgent and passionate feel. The lyrics describe the workers’ sacrifice: “day and night curing fellow human beings” (ngày đêm cứu chữa cho đồng loại), “they have put on a shirt of sacrifice” (khoác lên trên mình tấm áo hy sinh), “red eyes and no time to lament” (những đôi mắt đỏ au và không kịp thời gian để thở than). The song also uses war language, such as “front line” (nơi tuyến đầu) to refer to hospitals and “hands still save a world of gunpowder smell” (những bàn tay vẫn cứu lấy một thế giới của mùi thuốc súng). Another early song was “Wuhan Pandemic” (Đại dịch Vũ Hán), released by the musician Nguyễn Duy Hùng on January 31, 2020 (Nguyễn Duy Hùng 12h Official 2020). Although this song reached an even smaller audience, with under 400 views, the title shows the early perception of the Covid-19 virus as a “Chinese virus,” similar to later discourses in the West (Bushman 2022).

A more popular early song was “Fighting Corona” (Đánh Giặc Corona), which was released on February 17, 2020 and viewed more than 16,000 times (Trường Đại học Mở Hà Nội 2020). Similar to later songs, the lyrics combine educational messages, such as “remember we wear the mask for the sake of our safety” (nhớ khẩu trang ta mang vì lợi ích ta an toàn), with references to national solidarity, such as “unite all our people, from young to old” (Đoàn kết toàn dân ta, từ trẻ đến người già). A search on various online music sharing platforms shows other songs from early 2020 on the topic of Covid-19, including “Why Should the Children of the Fairy and the Dragon Be Scared of Corona” (Cháu Con Tiên Rồng Ngại Gì Corona) (Yến Tatoo Official 2020) and “Don’t Fall in Love with Cô Vy” (Đừng Yêu Nhầm Cô Vy) (Đỗ 2020). Both songs promote health measures like handwashing and social distancing. They also promote the need for public sacrifice. The first song, from April 2020, uses mythical and historical references and a more martial language with nationalist and war metaphors. The second song depicts some of the experiences of living with the containment measures.

Beyond the production of pandemic songs by local artists, content producers on social media engaged with the government’s social media campaigns, such as the TikTok campaign #onhavanvui (#happyathome). During the campaign, started by the MoH in March 2020, users were invited to post videos of different activities being done at home; the intention was to promote social distancing measures (VNNews 2020b). The online space allowed a more fun and relaxed form of communication on social media in comparison with the martial rhetoric described above.

Discussion

As mentioned above, state communication in Vietnam is challenging to assess due to a continuous choice between engagement and ignoring on the part of the public. Due to the omnipresence of propaganda posters, public engagement with these and their messaging is questionable (Bayly 2020; Robert 2020, 4).

As seen with the posters above, in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic many posters employ similar styles, colors, symbols, and messages. They become part of the state representation in public spaces without being able to dominate the spaces. However, they are still part of the state narrative on the relationship between state and society. This becomes even more obvious when compared with the messaging in social media content as we look at the example of music videos propagated by the state authorities. Here, citizens voluntarily engage with content, pushing streaming and like/dislike numbers.

Comparing both mediums of communication, it becomes clear that the focus of the messaging follows similar motives and narratives. Posters in public spaces and online videos frame the pandemic in similar narratives to support a similar aim.

Overall, three major narratives can be identified from our datasets: (1) patriotism and historical references, (2) morality and solidarity, and (3) the use of scientific and factual framing regarding containment and preventive measures for public health.

Generally, all communication material has at least some simplified messaging on public health measures, particularly handwashing, mask wearing, and social distancing. However, these scientific health messages are embedded in a normative and patriotic framing. Thus, while both online and offline communication aim primarily to distribute information on preventive measures and increase awareness of the risk of Covid-19 infections, both forms of communication also aim to reframe state-society relations and the role of citizens during the pandemic.

Citizenship in the Framework of Patriotism

State symbols like the Vietnamese flag, its star, and its red color are predominantly used in communication material offline and online. Often slogans reference previous wars or use wartime rhetoric such as “fight,” “soldiers,” and “sacrifice.” Following Nguyen-Thu’s (2020) argument, the data from this paper support a clear focus of the propaganda on social responsibility and community and an underlying sense of patriotism. The referencing of heroism combined with war rhetoric has strong cultural and historical roots in a country only two generations removed from the last war ending in 1979. From this perspective, cooperative citizenship is rooted in the patriotic idealization of Vietnam and the need to fight for the country’s future. This patriotic perspective is present also in the heroization of health-care workers seen in some of the visual material. The heroic framing depicts the sacrifice of health-care workers as a social ideal while, on the other hand, highlighting their fighting spirit as the foremost protectors of the nation, demanding gratitude.

Citizenship as a Normative Framework

Besides the patriotic narrative, a normative framework is also used to frame the pandemic. This is closely linked to the heroic role of health-care workers and their perceived sacrifice. In this context, compliance with public health measures is no longer defined as a logical decision but as a moral obligation enforced by public pressure, as represented by the female gaze in some of the posters discussed above. Social responsibility and solidarity are central concepts implied in the messaging. Going to the doctor and washing hands become moral obligations when juxtaposed with the suffering and sacrifice of those fighting at the front line, that is, health-care workers. Consequently, those not complying become enemies, hindering the fight against the pandemic and being rendered outside of the community of fate consisting of the Vietnamese state and its citizens. The normative framework, which evokes a moral dimension, thus works as a unifying element. However, while represented in posters, only in the social media sphere can it be reproduced by citizens and thus be enforced.

Morality of Caring and Cooperative Citizenship

In the context of the pandemic, the negotiation of citizenship as state-society relations rooted in rights and obligations is framed, on the one hand, in terms of patriotic heroism and a collective fight and, on the other, as a moral obligation rooted in sacrifice, social responsibility, and solidarity. Both narratives can be summarized into the idealization of a cooperative citizenship that puts social pressure on the community to comply or care for the common good—here, public health. This also pits the individual against the community: Whereas the individual might resist or ignore the messaging on the pandemic, the collective, symbolized in the female gaze in the posters above, reproduces and enforces the normative and patriotic construction of citizenship. From this, a morality of caring emerges, which moves citizenship from a political and social framework defining state-society negotiations into a mythical realm that demands individual and collective sacrifice, compliance, and responsibility in the name of the nation.

However, as Nguyen-Thu (2020) argues, the choice to follow Covid-19 regulations, including mask wearing, handwashing, social distancing, and quarantines, is also a personal and collective choice toward the “common good.” The protection of the community is thus not only a top-down demand but a bottom-up choice to protect one’s community and neighborhood. This can be seen in the broad engagement in poster competitions and online engagement as well as neighborhood support networks. Thus, at least at the beginning of the pandemic, individual responsibility toward the community, a sense of solidarity, and moral obligation were reproduced not only in state communication but also in social interactions and the individual framing of the pandemic. The idea of cooperative citizenship is thus no longer a top-down concept but a bottom-up demand toward the state to address the public health crisis.

Conclusion

The visual narratives in the Vietnamese government’s communication strategy are aimed at mobilizing all citizens to adhere to Covid-19 regulations. They are also a tool to gain political trust and legitimacy. The communication strategy is embedded in an idealized vision of cooperative citizenship based on a moral obligation toward the Vietnamese nation. The focus is on morality of caring, which is represented in all state communication to teach what is understood as morally correct behavior. However, over the course of the pandemic, new conflicts on participation and transparency, as well as questions of political competence, emerged. Nguyen-Thu (2020) rightly points toward a lack of democratic process and states that the emerging transparency in public health communication at the beginning of the pandemic was neither sustainable nor translated into other aspects of the political discourse. While social engagement, particularly in social media communication, is encouraged, the overall communication strategy is still dominated by a top-down approach. The combination of morality and patriotism dominates the framing, creating a sense of collective responsibility but also social pressure and exclusion for those seen as not complying. The ideal of cooperative citizenship is embedded in a morality of caring which defines state-society relations in the context of the pandemic as a community of fate that aims to reduce space for pushback and increase government legitimacy. However, some evidence from 2021, with increasing infection and death cases in 2021 and a decrease in transparency, points toward a certain mistrust concerning the state’s capacity to deal with the crisis and a reduced legitimacy. Instead, local and private networks of support address rising difficulties, contesting the notion of cooperative citizenship while transferring the morality of caring from a state-centered narrative toward a social discourse.

Accepted: September 15, 2023

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the organizers and conveners, Le Phan Ha, Liam Kelley, Jamie Gillen, and Catherine Earl, of the annual Engaging With Vietnam Conference for supporting the development of this research paper.

References

AFP and Asia News Network. 2021. A Third of Vietnamese Put under Lockdown. Phnom Penh Post. July 20. https://www.phnompenhpost.com/international/third-vietnamese-put-under-lockdown, accessed February 10, 2022.↩

Baehr, Peter. 2005. Social Extremity, Communities of Fate, and the Sociology of SARS. European Journal of Sociology 46(2): 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000397560500007X.↩

Bayly, Susan. 2020. Beyond “Propaganda”: Images and the Moral Citizen in Late-Socialist Vietnam. Modern Asian Studies 54(5): 1526–1595. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X19000222.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Berenschot, Ward; Nordholt, Henk Schulte; and Bakker, Laurens. 2016. Introduction: Citizenship and Democratization in Postcolonial Southeast Asia. In Citizenship and Democratization in Southeast Asia, edited by Ward Berenschot, Henk Schulte Nordholt, and Laurens Bakker, pp. 1–28. Leiden: Brill.↩ ↩

Binh Trinh. 2021. Living in Uncertainty: Prosperity and the Anxieties of NGO Middle-Class Women in the Context of Marketisation and Privatisation in Vietnam. Asian Studies International Journal 1(1): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.47722/ASIJ.1001.↩ ↩

Biti’s Hunter. 2020. Vietnamese Sneaker Brand Biti’s Hunter Made Themselves a Canvas to Feature the Nation’s Prideful Initiatives in the Face of Covid-19. CISION, PR NewsWire Asia. April 13. https://en.prnasia.com/releases/apac/vietnamese-sneaker-brand-biti-s-hunter-made-themselves-a-canvas-to-feature-the-nation-s-prideful-initiatives-in-the-face-of-covid-19-277331.shtml, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Bui Trang. 2020. Aggressive Testing and Pop Songs: How Vietnam Contained the Coronavirus. Guardian. May 1. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/may/01/testing-vietnam-contained-coronavirus, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Bushman, Brad. 2022. Calling the Coronavirus the “Chinese Virus” Matters: Research Connects the Label with Racist Bias. Conversation. February 18. https://theconversation.com/calling-the-coronavirus-the-chinese-virus-matters-research-connects-the-label-with-racist-bias-176437, accessed February 10, 2023.↩

Chinese Home. 2020. Ghen Cô Vy (Chinese version) [Jealous coronavirus (Chinese version)]. YouTube video. The original video has since been taken down, however others have covered the Chinese version of the song. Vân Thanh. 2020. Ghen Cô Vy – Cover Tiếng Trung (Chinese sub) [Jealous coronavirus – Chinese Cover]. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kA0VaZpVIAs, accessed February 9, 2024.↩

Communist Party of Vietnam Online Newspaper. 2020. Vietnamese Artists’ Propaganda Posters Praised on British Newspaper. April 10. https://en.dangcongsan.vn/vietnam-in-foreigners-eyes/-550494.html, accessed February 19, 2024.↩

Công an Nhân dân Online [People’s Public Security Online]. 2020. Phát hành tranh cổ động phòng chống dịch Covid-19 [Publication of posters to fight against Covid-19]. Cổng thông tin điện tử học viện cảnh sát nhân dân [People’s Police Academy Portal]. March 17. http://hvcsnd.edu.vn/photo/phat-hanh-tranh-co-dong-phong-chong-dich-covid-19-373, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Dabla-Norris, Era; Gulde-Wolf, Anne-Marie; and Painchaud, Francois. 2020. Vietnam’s Success in Containing COVID-19 Offers Roadmap for Other Developing Countries. IMF Asia and Pacific Department. June 29. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/29/na062920-vietnams-success-in-containing-covid19-offers-roadmap-for-other-developing-countries, accessed February 10, 2021.↩ ↩

Dao Quang Vinh. 2021. COVID-19 in Vietnam: Containment Measures and Socio-political Impacts. Report, Hans Seidel Stiftung (HSS), Asia Fighting Covid. https://www.hss.de/fileadmin/user_upload/HSS/Dokumente/Weltweit_aktiv/02_Vietnam_Vinh_Fighting_Covid-19.pdf, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Đỗ Hoàng Dương. 2020. Đừng yêu nhầm cô vy – Đỗ Hoàng Dương [Don’t fall in love with Cô Vy – Đỗ Hoàng Dương]. YouTube video. April 2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xVqshVQFwaw, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Ebbigenhausen, Rodion. 2020. Vietnams Kriegserklärung an Corona [Vietnam’s declaration of war on corona]. Deutsche Welle. April 23. https://www.dw.com/de/vietnams-kriegserkl%C3%A4rung-an-corona/a-52923517, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Ehlert, Judith. 2012. Beautiful Floods: Environmental Knowledge and Agrarian Change in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Berlin: LIT Verlag.↩

Flusberg, Stephen J.; Matlock, Teenie; and Thibodeau, Paul H. 2018. War Metaphors in Public Discourse. Metaphor and Symbol 33(1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2018.1407992.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Giao M. 2020. Mỗi Người Dân Là Một Chiến Sĩ Phòng Chống Dịch Bệnh [Every citizen is a soldier fighting the disease]. Thanh Nien [Youth]. March 24. https://thanhnien.vn/moi-nguoi-dan-la-mot-chien-si-phong-chong-dich-benh-post938509.html, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Gibert, Marie and Segard, Juliette. 2015. Urban Planning in Vietnam: A Vector for a Negotiated Authoritarianism? Justice Spatiale/Spatial Justice 8(1): 1–25.↩

Glik, Deborah C. 2007. Risk Communication for Public Health Emergencies. Annual Review of Public Health 28: 33–54. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144123.↩ ↩

Harms, Erik. 2016. Luxury and Rubble: Civility and Dispossession in the New Saigon. Berkeley: University of California Press.↩

Hartley, Kris; Bales, Sarah; and Bali, Azad Singh. 2021. COVID-19 Response in a Unitary State: Emerging Lessons from Vietnam. Policy Design and Practice 4(1): 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2021.1877923.↩

Hayton, Bill and Tro Ly Ngheo. 2020. Vietnam’s Coronavirus Success Is Built on Repression. Foreign Policy. May 12. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/12/vietnam-coronavirus-pandemic-success-repression/, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Hoang Ha. 2020. K-Pop Male Androgyny, Mediated Intimacy, and Vietnamese Fandom. In Mobile Media and Social Intimacies in Asia, edited by Jason Vincent Cabañes and Cecilia S. Uy-Tioco, pp. 187–203. Dordrecht: Springer.↩

Humphrey, Chris. 2020. “In a War, We Draw”: Vietnam’s Artists Join Fight against Covid-19. Guardian. April 9. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/apr/09/in-a-war-we-draw-vietnams-artists-join-fight-against-covid-19, accessed February 8, 2024.↩ ↩

Huyện Bình Chánh [Bình Chánh District]. 2021. Thông điệp 5K: Trong phòng chống đại dịch Covid-19 [5K message: In the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic]. Trang thông tin điện tử Trung tâm Y tế Huyện Bình Chánh [Website of Bình Chánh District Medical Center]. February 5. https://trungtamytebinhchanh.medinet.gov.vn/thong-tin-truyen-thong/thong-diep-5k-trong-phong-chong-dai-dich-covid-19-c13763-39095.aspx, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Kerkvliet, Benedict J. Tria. 2010. Governance, Development, and the Responsive–Repressive State in Vietnam. Forum for Development Studies 37(1): 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410903558251.↩

Khánh Hà. 2020. Thiết kế poster cổ động “Chung tay đẩy lùi COVID” [Designing the poster to promote “Join hands to prevent and fight the Covid-19 pandemic”]. Cổng thông tin điện tử thành phố Đà Nẵng [Đà Nẵng Portal]. August 10. https://www.danang.gov.vn/chinh-quyen/chi-tiet?id=40494&_c=100000150, accessed February 10, 2021.↩ ↩ ↩

Kirubakaran, Pragadish. 2020. From Propaganda Posters to War Rhetoric: How Vietnam Is Winning the War against COVID-19. Republic World. May 19. https://www.republicworld.com/world-news/from-propaganda-posters-to-war-rhetoric-how-vietnam-fights-coronavirus/?amp=1, accessed February 10, 2021.↩

Koh, David. 2006. Wards of Hanoi. Singapore: ISEAS Publications.↩