Contents>> Vol. 14, No. 1

Festivals in a Time of War: Pasar Malam in Japanese-Occupied Indonesia

William Bradley Horton*

*Faculty of Education and Human Studies, Akita University, 1-1 Tegatagakuen-machi, Akita City 010-8502, Japan

e-mail: dbroto[at]gmail.com

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6469-7877

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6469-7877

DOI: 10.20495/seas.14.1_109

The advent of World War II in 1940 and the occupation of the Indies by the Japanese military for almost three and a half years were great shocks to residents of the Indies and brought about innumerable changes. However, the commonly reproduced cartoonish image of a nation uniformly suffering under the yoke of arbitrary Japanese military overlords from 1942 to 1945 was not particularly apt. The beloved Indonesian pasar malam festival is assumed to have vanished during the wartime years, as has been explicitly claimed in the case of the Pasar Malam Gambir. In fact, while somewhat unstable during the wartime years, the institution of the pasar malam never really disappeared, and 1943 could even be described as the “Year of the Festival” due to the relatively high visibility of pasar malam around Indonesia. Examinations of newspaper articles and published programs help to show how these festivals continued to be socially, economically, and even administratively important in somewhat new ways, foreshadowing postwar changes.

Keywords: pasar malam, Japanese occupation, Indonesia, propaganda, entertainment

In Indonesia, a traditional event called a pasar malam (night market) has been organized annually in many locales, reportedly since the early nineteenth century. Although it is called a night market, it is neither a market nor open exclusively at night. Still, money does change hands. Developing in parallel with the world’s fairs of Western countries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Rydell 1984; Mitchell 1991; Bloembergen 2006) and even Japan (Ruoff 2010), it is a large-scale festival blending enlightening exhibitions, entertainment and activities, and cafes and restaurants. Gradually developing over time—like Dutch colonialism itself—the pasar malam came into its own in the early twentieth century, displaying the marvels of the modern Western world. Along with it came other kinds of exhibitions, the most extensive being the international Semarang Koloniale Tentoonstelling (Colonial Exhibition) of 1914, which could be compared to some world’s fairs (see Heel 1916 and various issues of the local daily De Locomotief from 1914). The Semarang Colonial Exhibition welcomed 677,266 visitors and included pavilions from Australia, China, Formosa (Taiwan), and Japan in addition to those of Indonesian regions and a number of large companies. There were also professional exhibitions held in Indonesia, like the Rubber Exhibition at the International Rubber Congress in Batavia (Jakarta) in October 1914, but such professional exhibitions had very different audiences than the pasar malam. Most pasar malam were local affairs with large popular audiences seeking entertainment.

Organization of a large-scale event was both complicated and costly; while an organizing committee could easily be formed, some form of support from both government and business was almost always essential. The interests of those institutions were essential and likely to run counter to the popular expectations of entertainment. Each pasar malam was thus a unique blend of what could be assembled given the specific kinds of support offered by interested parties and the particular local context.

During the final decades of the Dutch colonial era, the government in the colonial capital played a central role in holding an annual pasar malam in Batavia for about two weeks before and after the queen’s birthday on August 31. One of the major festivals in Indonesia, the Pasar Malam Gambir was not held in 1940 or 1941, due to the war in Europe and the occupation of the Netherlands. Smaller, more irregularly scheduled pasar malam, however, still were held throughout the colony. Chinese organizations, for example, held numerous small pasar malam as fundraisers for charities. For example, in October 1941 a pasar malam was held in Surabaya, Java’s second-largest city. Despite taking place two months before the eruption of the Pacific War and the Netherlands East Indies’ declaration of war on Japan, 50 percent of its proceeds were donated to the war fund, 25 percent to the ambulance fund, and 25 percent to Chinese charities. The native Indonesian political party Parindra’s affiliated organization Roekoen Tani (Farmers’ Association) also held a pasar malam and agricultural exhibition in Paree (Kediri) to coincide with its congress in October 1941 (De Indische Courant, September 20, 1941).

The long-anticipated war reached Indonesia in December 1941 with the Netherlands East Indies’ declaration of war. After only three months, on March 9, 1942, the Dutch surrendered to the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces. With the complete occupation of Indonesia and establishment of three regional military administrations, both the Japanese military administration and Indonesian society began to change at a dizzying pace. A contradictory blend of the convenient status quo and ideologically essential radical change initially appeared. Even as all sides were still making adjustments, pasar malam began to appear throughout the areas of Java controlled by the 16th Army.

These festivals, like virtually anything that could be construed as positive or pleasant during the Japanese occupation, have been systematically forgotten, at least in public discourse. In the context of the struggle against the returning Dutch or within the sphere of domestic politics, collaboration—or even the perception of benefiting from the Japanese occupation—was dangerous to individuals and the Republic itself. One of the very few passing references to pasar malam can be found in a short article on the Nippon Eigasha Jakarta Studio in a massive 700-page encyclopedia on the war in Indonesia (Okada 2010, 367; Post 2010). The very existence of pasar malam begs examination and explanation about their content and functions in wartime Indonesia under Japanese military administrations.

Early Wartime Festivals

While it is far from certain that this was the first held after the Japanese arrived, a pasar malam was held in Bandung beginning on August 1, 1942; this festival was visited by high-level Japanese officials and reported about in the local Indonesian press. During the next several months, additional pasar malam were held in numerous cities and towns on Java, including in Jogjakarta and Semarang in October.

The Bandung pasar malam of 1942 was an important event for the Japanese occupation, and the cover of the program booklet proudly states that it was produced by the Barisan Propaganda (Propaganda Front) of the Japanese government with the assistance of the City of Bandung. The opening ceremony was held on August 1, around 6 p.m. Local clocks had been adjusted 90 minutes ahead to Tokyo time on March 27, 1942, meaning that it was still quite light. Both Indonesian and Japanese attendees at the opening ceremony, sitting in rows of sturdy wooden chairs, seemed very relaxed and familiar with the activities and with each other. The speakers stood on the lawn in front of one of the pavilions, surrounded on three sides by the audience.

According to the extremely succinct opening speech by Yokoyama Ryuichi, a prominent cartoonist who represented the Propaganda Section, the purpose of the pasar malam was to provide residents a broad perspective on original arts and culture as well as the Indonesian economy in particular and Asia’s economy in general. The Dutch- and German-educated mayor of Bandung, Raden A. Atmadinata,1) immediately expanded on this theme more enthusiastically, explaining the importance of pasar malam for the economy, because people could understand crops and handicrafts of various regions; this provided a kind of map for trade—where goods could be found and where products might be sent. At the same time, the games and cultural performances would not only entertain but also help plant the seeds of love for the national culture and arts (Pasar Malam Ra’jat Bandoeng 1942).

While an Indonesian-language program was printed, coverage of the Bandung pasar malam in the press provides a relatively good sense of what the administration wanted to emphasize. Military officials toured the various exhibits, and photographs were printed in the Indonesian weekly magazine Pandji Poestaka one week after the opening ceremony, helping to show some of the exhibits as well as the participation and approval of the Japanese officials. The cover of that issue, of necessity striving to appeal to local people, shows the opening gate with masses of people milling around, flags and loudspeakers on poles, and even a Ferris wheel in the background. The photographs of the opening ceremony clearly show the pavilion of the Body for Information about Woven Cloth, while other pictures show the Nippon Kan with its “beautiful pictures” of nature and also of the Pacific War. Military officials are shown touring the national publisher Balai Poestaka’s display with its reading materials for the public, the Nippon Kan with its pictures on the outside wall, and an agricultural section showing local agricultural methods.

The pasar malam apparently met with the approval of both Japanese military officials and the Indonesian community, as it was extended five days, from August 19 to 23, and a flyer was printed to supplement the printed catalog.2) This flyer is also instructive in showing the daily events that made the pasar malam important. Tickets were sold only from 6 p.m., and entry was allowed from 7 p.m. except on Sunday, when it was open from 1 p.m. Performances of stories such as “Tengkorak” (Skulls), “Mantoe Prijijai” (Aristocratic son-in-law), “Oelar jang Tjantik” (Beautiful snake), and “Dasima” were performed by the Opera Moulin Rouge Revue every day. Most of these stories were well-known from prewar novelettes and even films. One of two traditional historical drama troupes (ketoprak) performed every day, while Cabaret Miss Mimi performed various dances from around Indonesia and the world daily. There were also wayang golek performances by Dalang Atmadja, and of course music of various kinds, including Angklung Garut, which had toured in Japan, and sports such as boxing.

The other pasar malam of significance in 1942 was the Jakarta “Pasar Malam Gambir,” which had been canceled for two years (Pemandangan di Pasar Malam 1942). Beginning on September 3, 1942, on a somewhat reduced scale, the pasar malam was officially held to commemorate six months of Japanese occupation, and the Japanese army probably hoped to follow its slogan of “grabbing the hearts of the people” in an attempt to get closer to the Indonesian people. This pasar malam included Japanese industry and military equipment, a special building focusing on social affairs sponsored by the city government, a special handicraft room with weaving, wood products, sea products, jamu (traditional medicine) stands, keroncong3) singing, and sports such as wrestling—even though there was a major sports festival during the same period.

As noted in a critical discussion of a crowded exhibition of paintings by Indonesian artists, the pasar malam was also a place to have fun (St. 1942, 848), not to think or seriously consider things. The Jakarta pasar malam was held close to the traditional time in early September (September 3–13, 1942). One of the featured activities was singing songs, and children were the focus in at least one event, led by the composer Koesbini and with various VIPs like Deputy Mayor H. Dachlan Abdoellah and the chair of the pasar malam organizing committee sitting on the dais listening to the children sing. During the next year, high-profile pasar malam were the rage, serving a special role in the political economy of mass mobilization.

Fig. 1 Making Children Happy in the Jakarta Pasar Malam of 1942 (Pandji Poestaka 20[24] [1942]: 835)

Smaller festivities were held throughout Java for other occasions, such as Meiji-Setsu, a celebration of the nineteenth-century Meiji emperor’s birthday on November 3. One such event was in Surakarta (Solo), where a four-day celebration was held between November 1 and 4, 1942 (Komite Perajaän 1942). The first day merely had an opening speech by the chair of the organizing committee, Mr. K. R. M. T. Wongsonagoro, on the Solo radio station at 8:45 p.m. Each day there were music performances, films, as well as various traditional performances such as Golek Mataram, wayang orang, and ketoprak. On the third day, twenty-five thousand schoolchildren collected at their schools and then went to designated locations for ceremonies. There were also some sports activities on the third and fourth days. Most—or possibly all—of these activities and performances were free and held at preexisting facilities throughout the city center.

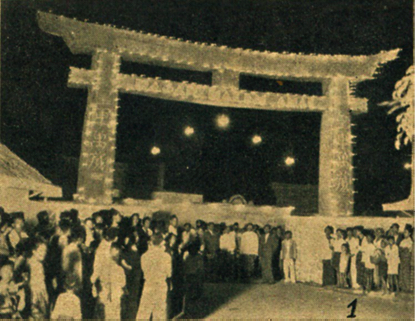

Fig. 2 The Japanese-Style Gate of the Pasar Malam in Modjokuto, East Java, in September 1942 (Pandji Poestaka 20[24]: 839)

June–October 1943 Festivals

On June 16, 1943, Japanese Prime Minister Tojo Hideki announced that Indonesians would be allowed to participate more in government, albeit gradually. It was a relatively peaceful period of the war, at least in western Indonesia. Plans for pasar malam were already in motion in various places, including Jakarta. The pasar malam in Jakarta was scheduled to be held daily from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. from June 25 to July 15 (21 days). In colonial times, the pasar malam was held in late August and early September for two weeks and one day to celebrate Queen Wilhelmina’s birthday. The Japanese daily Jawa Shinbun (June 24, 1943) published eight photographs in a set of articles under the heading “Pasar Malam Opens Tomorrow” showing some of the Rakutenchi (former Prinsenpark) festival grounds. The 1943 pasar malam grounds occupied nearly twice the area of the previous year.4)

Under the leadership of the large construction company Obayashi Corporation, a number of new pavilions had been built, older pavilions renovated, and new decorations created with a large budget (Jawa Shinbun, June 24, 1943).5) Some of these buildings were the New Java Industrial Hall, Japan Industry Hall, and Poetera Hall. Poetera stood for Poesat Tenaga Ra’jat, or Center for the People’s Power, and was the mass organization of the time which the military administration hoped would help promote cooperation with the administration in labor recruitment and other affairs; Poetera allowed Indonesian nationalists to reach a large public on Java. In addition to the pavilions intended to enlighten visitors, such as a building for the Assembly of the People’s Forces formed in January, the Health Hall, and the Photo Gallery, there was also an athletic stadium, a music hall, a theater, a movie theater, an aquarium, a cafeteria, and a shop. At the Japan Industry Hall, products from twenty companies such as textiles, electrical products, oil, rubber, and beer were displayed, while in a photo exhibition the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shinbun exhibited 108 photos introducing Japan, providing an opportunity for visitors to learn about the country. The Poetera Hall also provided support for war and the Fatherland Defense Volunteer Army. The Bintang Surabaya Theater Company, the Bintang Jakarta Theater Company, and Miss Tjitjih’s Theater Company performed regularly in addition to various Javanese entertainers, including theater troupes, traditional dancers, gamelan ensembles, and martial arts specialists from West Java. There were also performances such as Javanese shadow puppet plays (wayang kulit) and benjang, which was described as a mix of Indonesian pencak martial arts, American wrestling, sumo, and jujutsu (Jawa Shinbun, June 24, 1943; Pembangoen, July 3, 1943; Nippon Eigasha Djawa 1943a). In short, there was a wide range of events that combined enlightening activities and entertainment, information about Japanese society, and a display of Indonesian culture. It was a celebration.

All things were not equal at the fair, however. While there was an entry fee, many of the performances had additional fees, which would have made it difficult for many children and poorer people to attend. Other parts of the fair were free, and gamelan was played on a tower, allowing everyone to hear the music. Most free things were in “educational” sections with photographs or displays intended to educate the visitor, although that was not necessarily seen as bad. Asia Raya (July 14, 1943) called attention to one such free educational item: the “Poetera” Agricultural Quiz, which could be entered with a postcard and with prizes of ƒ10–25 paid for by Asia Raya, ƒ5–7.5 paid for by another Jakarta daily, Pembangoen, and ƒ2.5 paid for by Poetera itself. Additionally, there were exhibitions and descriptions of medical supplies that could be made locally (one was described in detail in the newspaper), information related to aquafarming, and explanations related to the production of soap for personal use. All of these provided educational, economic, and perhaps other social benefits to attendees.

Fig. 3 The Gamelan Music Platform (Pandji Poestaka 21[20/21] [1942/1943]: 763)

A Sundanese commentator writing in Pandji Poestaka as a “grandfather” described the crowded atmosphere on the opening night, where he was dragged against his will, and expressed his excitement about the peaceful “Eastern” atmosphere. However, he lamented that some of his “grandchildren” did not take advantage of the opportunity to learn, as there were handicrafts that could replace many foreign goods that could not be obtained any more—although in his opinion tennis balls were still a problem as he was crazy about tennis. He resolved to not push his grandchildren anymore, or they would not even give him a cup of coffee (Aki Pangebon 1943, 762). This humorous article was perhaps the strongest statement of the organizing and sponsoring elites, as the author claimed that the whole purpose of going to the pasar malam was really to see things that could provide financial or other real benefits to the fairgoer.

Fig. 4 Local Handicrafts at the Pasar Malam Jakarta in 1943 (Pandji Poestaka 21[20/21] [1942/1943]: 764)

The pasar malam was meant to draw as many people as possible. Special streetcar and bus services were provided to and from various parts of the city, as well as to and from the major train stations, until midnight. Traffic around the fairgrounds was subject to special restrictions. The entrance fee was 10 cents for Indonesian adults and 5 cents for Indonesian children, but double for Japanese, Arabs, Chinese, Indians, and other ethnic groups. On July 4, between 12 noon and 2 p.m., all performances were free in order to provide an opportunity for students, soldiers, and the poor. This special occasion drew more than ten thousand people during the day, which was very unusual (Pembangoen, July 3, 1943; July 5, 1943). Other times, in addition to entry tickets there were performances and activities with additional charges. About four hundred thousand people visited the event over the 21 days, the proceeds were donated to charity, and the pasar malam was declared a success. Naturally, some of the information that the Japanese military administration (including Indonesian civil servants) wanted disseminated would have reached many of the attendees.

Fig. 5 The Pasar Malam Jakarta (小野佐世男ジヤワ從軍画譜 1945)

More than any photograph could, the Japanese illustrator Ono Saseo, who spent the entire war attached to the Propaganda Section of the 16th Army on Java, captured the atmosphere of chaotic merriment, with men, women, and children crowded into the area, each doing their own thing: children walking hand in hand with parents; mothers bending over their reluctant children; squatting children; as well as adults talking, walking, or looking around. The illustrations also show balloons, a Ferris wheel, and other activities fading into the distance, and a large banner reading “Djakarta.” Taken in this context, pictures of stage plays (sandiwara), dancing, and the night scenery in the popular semi-bilingual magazine Djawa Baroe are more meaningful.

The Pasar Malam Jakarta of 1943 was important enough to be covered in a significant newsreel story (Nippon Eigasha Djawa 1943a) emphasizing the goal of defeating the enemy and showing that this pasar malam was better than those of previous years. The newsreel story showed the making of thread, an aquarium, agricultural products, the Poetera Hall, handicrafts of the women’s section, agricultural methods, the merry-go-round, and the general scenery of the pasar malam. Interestingly, there was a short section showing the health section with a clinic, which included both a mock display and apparently real doctors and nurses examining and treating a patient.

During the course of the pasar malam, on July 7, Japanese Prime Minister Tojo arrived in Jakarta for a brief visit to Java during his trip through Southeast Asia, returning to Tokyo by July 12. His visits to schools, reception by the public on the road to and from the airport, meetings with local VIPs, and public addresses to large groups of Indonesians had a significant impact. The special issues of Pandji Poestaka and Djawa Baroe at the time mixed extended coverage of the prime minister’s activities and various important people’s reactions to his visit on the one hand with the pasar malam on the other, creating what must have been an exciting atmosphere for many. Things were happening in peaceful wartime Java. Two weeks after the fair, the large port city on the other end of Java, Surabaya, was bombed by the Allies for the first time, bringing the war a little closer.

Pasar malam were still held in various other places in the same year, giving the illusion that life in Indonesia had returned to normal. Bandung held a pasar malam in July, while Malang in East Java also held a fair and published a catalog. Extant pamphlets reveal war slogans along with the color-printed advertisements and cultural performance schedules. The war was there.

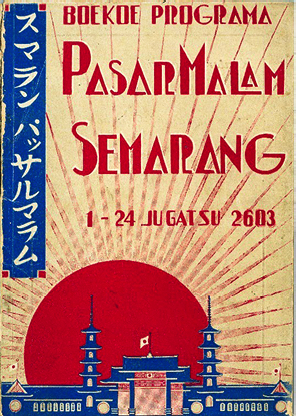

One of the pasar malam later in the year was in Semarang, the large port city in north-central Java. This pasar malam was held on October 1–24, coinciding with the Muslim Lebaran (Idul Fitri) holiday at the end of the fasting month. As with pasar malam in other areas, the date of the Semarang event seems to have been consciously set in a different time frame than in the colonial past. In 1934 it had been held from July 24 to August 12.

With a large rising sun casting warm red light everywhere and a mixed Indonesian- and Chinese-style building graced with Japanese flags on the cover, a program booklet provided detailed information about the schedule and organization of the pasar malam. This booklet indicated that the event’s purpose was to help defeat the Allies, and so the familiar slogan “Amerika kita setrika, Inggris kita linggis” (America we will flatten with an iron, England we will beat with a crowbar) was written in red letters at the bottom of each page. There was a special section on the “Planned Efforts to Defeat the Allies and Defend [Our] Homeland in the Pasar Malam Semarang,” listing speeches, comedy contests, and plays (p. 11) as well as poster and painting contests, slogan contests, and singing (p. 13). This was listed separately from the general program. Naturally, it was noted that the proceeds were to go to charities, as was common for most pasar malam.

Fig. 6 Program Booklet, Semarang Pasar Malam, 1943

Like in other program booklets, a large section was devoted to advertisements—in this case mixed throughout the book, but with more in the final sections. These could be very important in disseminating information about available products and services. Poetera was a major sponsor of the Semarang Pasar Malam, and the purposes and structure of both the main Java-wide organization and the Semarang area branch were presented. There was a section on health written by Dr. R. Soedjono Djoned Poesponegoro (Boekoe Programa Pasar Malam Semarang, pp. 33, 35) focusing on a few points to ensure good health. These addressed issues related to pregnant women, babies and children, food, cleanliness of the body and home, the importance of physical activity for health, and vaccinations. There was also a section on freshwater aquaculture by Moerdoko (pp. 37, 29) that described the characteristics and advantages of seven types of fish, increasing interest in the pasar malam aquaculture displays before the opening date. The final fish described was ikan Moedjair (Tilapia zillii), which had the potential benefit of helping to eliminate malarial mosquitos in some areas. Named after the Indonesian who first cultivated it, this fish was widely promoted during the war (Perihal Ikan-Moedjair 1945).

Sulawesi 1943

Java was not the only site of pasar malam held during the war, or even just in 1943. In Sulawesi, local governments and prominent residents actively organized festivals that seemed largely to be in line with Japanese administrative expectations. With the official holiday for the Japanese emperor’s birthday (April 29), Tenchōsetsu, approaching, a committee in Bone began to plan a three-day pasar malam, with daytime activities on those days (Pewarta Selebes [Makassar], March 11, 1943). Another pasar malam in Majene was scheduled for the next month. Around March 16, planning began for a large pasar malam in Bantaeng to be held in Lembangtjina/Bantaeng between April 24 and May 2, 1943 (Pewarta Selebes [Makassar], March 16, 1943). Bantaeng was a particularly important symbolic location, as it had been the site of a major battle in 1942.

Makassar also held a pasar malam in October 1943 for two weeks at its normal time. Film crews were on hand to record events for Berita Film di Djawa (Film news in Java), and a short segment made it to the Java newsreels in Indonesian and Japanese (Nippon Eigasha Djawa 1943b)—although with musical background unrelated to Makassar. The buildings shown in the film were made of local materials with thatched roofs rather than modern buildings like in the festivals on Java. Traditional dances that might appeal to distant audiences, as well as scenes of crowded audiences, were filmed for the news. Local newspapers presented the pasar malam very differently, showing badminton competitions and people looking at pictures in the Nippon Hall (Pewarta Selebes [Makassar], October 11, 1943). Boxing, basketball, and keroncong music were to close the 15-day pasar malam, which was extended for another two days. Besides boxing and sandiwara plays, the local newspaper discussed the competition among goen (administrative districts) for a prize awarded to the best agricultural products, and a whole range of similar activities.

Fig. 7 Badminton at the Makassar Public Pasar Malam, 1943 (Pewarta Selebes [Makassar], October 11, 1943)

Only a few days after the Makassar fair closed on October 17, the Goa pasar malam opened on October 20, 1943, about 50 km away (Pewarta Selebes, October 20, 1943).

A Shift in Atmosphere

The year 1944 seems to have brought a shift in the mood of the military administration, at least on Java, and along with that a shift in the mood of society. The desperation of the war situation for Japan could be felt in the urgency with which everything was—at least pro forma—directed toward the collective goal: the defeat of enemies, ultimate victory of Japan, and creation of a new Asia under Japanese leadership. While war occupied a greater percentage of newspaper content as the size and number of pages decreased due to paper shortages, shortages of food, clothing, medicine, and other goods developed to different degrees throughout Java, which also changed the general atmosphere.

By August 1943, the long-running magazine Pandji Poestaka had shifted to war-related images for its covers. These were often images of soldiers or civilians in military support roles, though there were periodic breaks with pictures of agriculture, children, or sports. The other major magazine published in Jakarta, the highly illustrated Djawa Baroe, did not fully switch to war-related images until around October 1944. However, this was part of a gradual shift during 1944 in imagery and mood, and naturally pasar malam were involved in this shift.

Pasar Malam in 1944

On September 7, 1944, the government of Japanese Prime Minister Koiso Kuniaki announced in the 85th Teikoku Gikai (Imperial Diet) session that Japan would grant Indonesia its independence in the future. A range of spontaneous as well as carefully calculated reactions and expressions of both joy and appreciation appeared throughout Java. On September 8, 1944, the head of the military administration on Java, the Saikō Shikikan, officially declared that the Indonesian flag was to be used alongside the Japanese flag and that the song “Indonesia Raya” was now recognized as the national anthem. On September 17, 1944, September 7 was declared “Indonesian Independence Promise Day.”

In Jogjakarta, a decision was made to hold a pasar malam in October in the hope that residents would be filled with joy “because there is indeed reason to be joyful” (Panitya Pasar Malam 1944, 1). The printed program contained the pasar malam committee’s explanation, followed by the national anthem—“Indonesia Raya” (p. 2)—an explanation from Prime Minister Koiso about Indonesian independence (p. 3), an explanation about official policies for the use of the national anthems and national flags (pp. 4–6), descriptions of the Central Javanese “princes” meeting with the Saikō Shikikan (pp. 7–8), and a statement by Sukarno and the fifth meeting of the Chuo Sangi In (the consultative body on Java). Finally, the leaders and main members of the pasar malam committee and the twenty subcommittees were listed, and the air raid procedures were explained. Only on pages 21–23 was the schedule explained. Following that were more essays on the steps toward independence, the constructive efforts of the pasar malam, and explanations about animal husbandry (especially chickens) and the issuance of clothes in the Jogjakarta area. The remainder of the 77-page booklet was made up of advertisements.

The tone of the booklet conveyed a restrained, mature, serious celebration. That this was a celebration is clearest from the daily scheduled performances of sandiwara dramas, wayang orang, wayang potehi Indonesia,6) and music. Sports such as soccer, kendo, boxing, sumo, and wrestling occupied multiple days, but kroncong singing occupied the final slot, closing out the 15-day fair.

Similar celebrations were organized throughout Java, although the timing and extent of the celebrations varied. Not all were designed as pasar malam; in fact, some preceded Koiso’s announcement. Pekalongan, a coastal city west of Semarang, had held its third annual Pasar Malam Kesenian (Cultural pasar malam) from July 22 to August 6. This pasar malam was “protected” by the Japanese regional head and assisted by the Barisan Propaganda of the Japanese Army. In fact, the social calendar on Java was quite packed with activities, including health campaigns, sports activities, and in December a celebration of the start of the war.

Areas outside of Java were somewhat different, as the war situation continued to worsen. Pasar malam continued to be held in Sulawesi, and in September–October 1944 the second page of the Pewarta Selebes almost always mentioned either events at the Makassar Pasar Malam Oemoem or the pasar malam scheduled for other regional towns in South Sulawesi. Along with these was explicit reference to the promise of independence, but it is not clear whether the pasar malam were explicitly designed in that context.

Conclusion

While far from complete, the descriptions that appear in wartime materials offer a picture of the pasar malam during the Japanese occupation as sites of entertainment and enjoyment for the public. These festivals were almost certainly larger, longer, and more common in the first two years of the war, when goods were a little easier to obtain and there was less of a foreboding feeling brought on by the encroaching Allies and the battles gradually approaching Japan and even Java. However, their presence throughout the wartime period and changing forms provides an opportunity to reconsider the places and functions of pasar malam, to consider changes over time, and to remember that in the end, life went on for the residents of Indonesia.

We have seen that often pasar malam appeared to be either charity events or responses to Tojo’s promise of greater political participation or Koiso’s promise of Indonesian independence. These “spontaneous” Indonesian responses must be viewed critically, but not entirely cynically, as everyone knew that such promises were never offered by the Dutch, nor had Japanese offered them earlier, though the Philippines and Burma had obtained a form of independence. It seems reasonable to expect that over two years the Indonesians and Japanese had learned to play a game together, and that the Indonesians knew it was important to respond positively, if only to ensure future benefits, and the Japanese knew that knowledge of such promises needed to be spread around. That was probably not difficult, as events like the 1942 Pasar Malam Bandung opening ceremony showed that Indonesian officials could be more serious about producing “real” economic results than Japanese.

More broadly, it seems that a culture that emphasized a serious purpose for everything was being created during the Japanese occupation, through the pasar malam and other activities. Publications blended into pasar malam promoted new forms of agriculture and aquaculture, whether for health reasons (eliminating breeding grounds for malarial mosquitos) or for food and income. Healthy sports activities and Japanese-language competitions came to have a place both within festivals and by themselves. Nonetheless, it would be a mistake to see such things as originating with the Japanese occupation—health officials and businesses had always seen the pasar malam as potential grounds for propaganda efforts. However, the notion of festivals being solely for enjoyment was gradually reduced and almost eliminated during the Japanese occupation, though the activities and the fun were not.

In 1944 and 1945 it was clear throughout Indonesia that the war was at a critical juncture, though the abrupt ending in August 1945 was not easy to foresee. The numbers of newspaper pages were reduced, magazine covers grew more military oriented, and more articles focused on the war. Creation of the Peta self-defense force meant that Indonesians themselves were involved in the military as well, as magazines like Pradjoerit (Soldier) (1944–45) and fiction like Karim Halim’s Roman-Pantjaroba Palawidja (Palawija, a novel of many changes) (1945) reminded readers. In urban areas, some people suffered from hunger due to food shortages; many rural areas were worse.

Pasar malam did continue. The Pasar Malam BPP Bogor in April 1945 and the headlining sandiwara Tjahaja Timoer were extended until April 18; boxing was held on April 11, soccer between April 13 and 15, and kroncong on April 14 (Asia Raya, April 9, 1945). A pasar malam scheduled in Madiun for July or August 1945 even had a “struggle” section, which—with local police approval—published biographies of three national heroes who had fought against the Dutch in earlier centuries (Panitya Pasar Malam Madioen 1945). Nonetheless, big pasar malam did not reappear until the end of the occupation, and even then, financial losses and political instability during the fighting between the Netherlands and the Republic of Indonesia resulted in the cancellation of a number of important pasar malam.

Reappearing and evolving during a short period when a “normal” life was possible for many, pasar malam were important for Indonesians at that time. However, it should not be forgotten that officially the pasar malam brought people together for serious purposes: learning important knowledge, moving toward independence, and, most important, the purpose of winning the war, a war that led to another war (1945–49) which most Indonesians were far more invested in. The pasar malam of the Japanese occupation are also a page in the history of the common people.

Accepted: October 15, 2024

Acknowledgments

Research for this paper was supported by JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 19H01321 (Principal Investigator, Mayumi Yamamoto). The assistance of many people was essential for materials and language help, including Mayumi Yamamoto, Didi Kwartanada, Hisashi Nakamura, Atep Kurnia, Heri Waluyanto, and Arya Anggara.

References

Asia Raya

De Indische Courant

Djawa Baroe

Pandji Poestaka

Pembangoen

Pewarta Selebes (Makassar)

Aki Pangebon. 1943. Lelab-Roembah [Garden stuff]. Pandji Poestaka 21(20/21): 762.↩

Asia Raya. 1945. Advertisement. April 9, p. 2. Available online at http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:3215471, accessed February 25, 2025.↩

Bloembergen, Marieke. 2006. Colonial Spectacles: The Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies at the World Exhibitions, 1880–1931. Singapore: Singapore University Press.↩

Boekoe Programa Pasar Malam Semarang 1–24 Jugatsu 2603 [Program book for the Pasar Malam Semarang, October 1–24, 1943]. 1943. Djakarta: Kantor Reklame dan Adpertensi “Korra.”↩

De Indische Courant. 1941. PASAR-MALEM IN PAREE. Van “Roekoen Tani.” Sept. 20, sheet 2, p. 2. https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ddd:011176309:mpeg21:p006, accessed on February 25, 2025.↩

Djawa Baroe. 1943. Pasar Malam Diboeka/パッサル・マラム開かる [Pasar Malam opens]. Djawa Baroe 1(13): 26.↩

Djawa Gunseikanbu. 1944. Orang Indonesia jang Terkemoeka di Djawa [Prominent Indonesians in Java]. Djakarta: Gunseikanbu.↩

Heel, M. G. van, comp. 1916. Gedenkboek van de Koloniale Tentoonstelling Semarang, 20 Augustus–22 November 1914 [Memorial book for the Semarang Colonial Exhibition, August 20–November 22, 1914]. 2 vols. Batavia: Mercurius.↩

Jawa Shinbun ジャワ新聞. 1943. 「戰ふ爪哇」の縮圖 七万坪に展く絢爛繪卷 [A Miniature of the “Battle of Java.” A gorgeous scroll spread over 70,000 tsubo]. June 24, p. 1.

Komite Perajaän. 1942. Atjara Perajaan Hari Besar MEIJI-SETSU 2602 Diselenggarakan oleh Komite Perajaän dari Segenap Pendoedoek Soerakarta [Festivities for the Meiji-Setsu holiday of 1942 organized by the celebratory committee from the entire population of Surakarta]. Solo.↩

Mitchell, Timothy. 1991. Colonising Egypt. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.↩

Nippon Eigasha Djawa. 1943a. Disinipoen Medan Perang (6), Berita Film di Djawa [The battlefield is here too (6): film news in Java]. Beeld en Geluid. https://zoeken.beeldengeluid.nl/program/urn:vme:default:program:2101608040030654731, accessed February 26, 2023.↩ ↩

――――. 1943b. Sekoetoe Haroes Roentoeh! Berita Film di Djawa no. 15 [The Allies must collapse! Film news in Java no. 15]. Beeld en Geluid. https://zoeken.beeldengeluid.nl/program/urn:vme:default:program:2101608040030618431, accessed February 26, 2023.↩

Okada Hidenori. 2010. The Rise and Fall of the Nippon Eigasha Jakarta Studio. In The Encyclopedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War, edited by Peter Post, pp. 363–370. Leiden: Brill.↩

Ono Saseo 小野佐世男. ジヤワ從軍画譜 [Illustrations of the Java Military attached Ono Saseo; collection of the drawings of Ono Saseo in participating in the war in Java], compiled by the Barisan Propaganda. 1945. Djakarta: Djawa Shimbun Sha.↩

Panitya Pasar Malam. 1944. Pasar Malam Jogyakarta: Memperingati Perkenan Indonesia Merdeka di Kemoedian Hari [Commemorating the granting of Indonesia’s independence in the future]. Jogjakarta: Panitya Pasar Malam.↩

Panitya Pasar Malam Madioen [Syuu Hookookai] Bahagian Pertoendjoekan Pembelaan. 1945. Riwajat dan Perdjoeangan Pahlawan-pahlawan Indonesia sepintas laloe [The history and struggles of Indonesian heroes in brief].↩

Pasar Malam Ra’jat Bandoeng [Bandung People’s Pasar Malam]. 1942. Pandji Poestaka 20(18): 627.↩

Pemandangan di Pasar Malam [Scenes at the pasar malam]. 1942. Pandji Poestaka 20(23): 808–809.↩

Pembangoen. 1943. Kabar Tontonan Pasar Malam [News of Pasar Malam performances]. July 3, p. 3.

Perihal Ikan-Moedjair [About the Moedjair fish]. 1945. B.P. No. 1589. Djakarta: Gunseikanbu Kokumin Tosyokyoku (Balai Poestaka).↩

Pewarta Selebes (Makassar). 1943. Pasar Malam Oemoem 2603 [1943 Public Pasar Malam]. October 11, p. 3.

Post, Peter, ed. 2010. The Encyclopedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War. Leiden: Brill.↩

Regeerings-almanak voor Nederlandsch-Indië. Tweede Gedeelte, Kalender en Personalia [Government almanac for Netherlands East Indies. Second part: Calendar and personnel]. 1942. Batavia: Lands-Drukkerij.↩

Ruoff, Kenneth. 2010. Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary. Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.↩

Rydell, Robert W. 1984. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876–1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.↩

St. 1942. Pertoendjoekan Loekisan Indonesia di Pasar Malam Djakarta (2–14 September 2602) [Exhibition of Indonesian paintings in the Pasar Malam Jakarta (September 2–14, 1942)]. Pandji Poestaka 20(24): 848–849.↩

1) Raden Atmadinata was also chair of the Bandung-based Nederlandsch-Indische Jaarbeurs (Netherlands-Indies Annual Market) for 1942 (Regeerings-almanak 1942, 627; Djawa Gunseikanbu 1944), so it is very likely that he was then the chair of the organizing committee for the pasar malam.

2) “Programa Pasar Malem, Samboengan dari tanggal 19 sampai 23 Hachigatsu 2602” [Pasar malam program, continued from August 19 to 23, 1942] (Bandung: Barisan Propaganda Dai Nippon, Bandoeng Syakuseo). Thanks are due to Heri Waluyanto for showing me this flyer.

3) A hybrid form of music popular in Indonesia in the early twentieth century

4) While Japanese-language sources stated the area of the 1943 grounds was 70,000 tsubo (1 tsubo equals approximately 3.3 m2, thus approximately 231,000 m2), the Indonesian-language text of Djawa Baroe stated it was 70,000 m2 (thus 21,212 tsubo). As Jawa Shinbun also states that the previous year occupied 36,000 tsubo, tsubo is probably the correct unit (Jawa Shinbun, June 24, 1943; Djawa Baroe 1943).

5) The total cost was listed as ¥XX0,000, a vague but not entirely meaningless figure.

6) A form of traditional Chinese puppetry