Contents>> Vol. 4, No. 2

The Emergence of Heritage Conservation in Singapore and the Preservation of Monuments Board (1958–76)

Kevin Blackburn* and Tan Peng Hong Alvin**

* Department of Humanities and Social Studies Education, National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, 1 Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616

Corresponding author’s e-mail: kevin.blackburn[at]nie.edu.sg

** Raffles Girls’ School, 20 Anderson Road, Singapore 259978

DOI: doi.org/10.20495/seas.4.2_341

Keywords: Singapore, preservation, conservation, monuments, sites

In Singapore, where a strong state has driven heritage conservation measures, there has evolved a distribution of conservation work between two state agencies—the Urban Redevelopment Authority and the Preservation of Monuments Board (known since 2013 as the Preservation of Sites and Monuments). The Urban Redevelopment Authority has designated whole conservation zones, while the smaller Preservation of Monuments Board has picked out individual historic monuments and buildings for preservation. The beginning of heritage conservation in Singapore lies with the events that led to the creation of the Preservation of Monuments Board in 1971. The Urban Redevelopment Authority did not commence its involvement in heritage conservation until much later. The Urban Redevelopment Authority’s designation of key conservation areas, such as Chinatown, Kampong Glam, and Little India, started only in the 1980s. Singapore’s heritage non-governmental organization, the Singapore Heritage Society, was not established until 1987. The Preservation of Monuments Board had already been listing historic buildings for conservation for 16 years. Studying the history of the creation of the Preservation of Monuments Board in Singapore reveals the forces behind the early emergence of heritage conservation in Singapore and how Western ideas and institutions provided models for heritage conservation in Singapore to follow.

Heritage conservation was often viewed as a luxury developing countries such as Singapore could not afford during the early years of independence. There was an urgency to rapidly industrialize and to maximize urban space for commercial development and modern housing through urban renewal. This has been taken to mean that little thought was given to heritage conservation by postcolonial governments until after significant economic development had occurred (Yeoh and Huang 1996, 411). However, Lily Kong, in her history of Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority, suggested an opposing view. She proposed that even during the intense period of demolition and rebuilding of urban renewal, there were advocates of heritage conservation within the bureaucracy “who persisted until their voices became more influential” (Kong 2010, 47). These voices, although present in the 1960s and 1970s, had to wait for a wider acceptance within the bureaucracy. Her argument is that Singapore government agencies “were not monolithic or homogenous”; instead “within those agencies and bodies, multiple voices seek to be heard” (ibid.). Lily Kong and Brenda Yeoh (2003, 131) make it clear that in Singapore, the “state’s engagement with issues of heritage” only occurred more fully at “a specific juncture of its development”—the 1980s and 1990s. However, the Preservation of Monuments Board had its genesis during the 1960s. Debates in the 1960s that led to the Preservation of Monuments Board’s creation might reveal more about these early voices of heritage conservation that Kong describes as not coming to the fore until much later.

Kong’s assertion that there were quiet heritage debates within the Singapore bureaucracy in the 1960s and 1970s is hinted at by some published material reflecting the thinking of the bureaucrats and the politicians. In one article, Alan Choe, who became in 1964 the first head of the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s predecessor, the Urban Renewal Department, asserted: “Contrary to misinformed belief, urban renewal does not mean just the pulling down of slum sections and rebuilding on the cleared area” (1969, 165). He argued: “There are actually three indispensable elements of urban renewal; conservation, rehabilitation and rebuilding. This would mean identification of the areas worth preserving; a programme to improve such areas and make them habitable with an improved environment; and an identification of the areas that must be demolished and rebuilt” (1968, 2–5). In a published interview, Choe even mentioned that in 1967 then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had approached him with his concern that not enough consideration had been given to preserving historic buildings in the rush by Singapore’s urban planners to engage in urban renewal (Straits Times, April 12, 2014). These published statements raise the question why there was not more of a balance between conservation and redevelopment of the urban landscape. This article uses recently declassified material in the Singapore state’s archives to answer this question and explore these early conservation debates.

Heritage debates that developed from colonial times into the early postcolonial period in other Asian countries have been influenced by what Denis Byrne has called a “Western hegemony in heritage management” spread “by a process of ideology transfer rather than imposition” (1991, 273). Ken Taylor (2004), expanding on Byrne, argued that Western heritage organizations, such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and Western codes of heritage preservation, such as the 1964 Venice Charter, were in the early debates over heritage conservation not culturally sensitive enough to incorporate traditional Asian views. Western notions of heritage conservation described in the Venice Charter have emphasized “authenticity” of the original building materials, while traditional Asian notions of heritage have seen little wrong with regular rebuilding and expansion of historic buildings that maintain “the spirit of the place” and the traditional skills needed to rebuild and expand (Byrne 1991, 275).

The Venice Charter, in particular, has been seen as delineating in Western terms the very definitions of heritage management in many of the early debates of the 1960s and 1970s (Winter 2014, 123). In the Venice Charter, conservation was synonymous with preservation. Conserving a building or site meant keeping it “authentic” and preserving it with no changes. Restoration contrasted with preservation. Changes to a historic building or site were limited by strict prohibitions allowing the use of only “original” and “authentic” materials in the restoration process. The Charter outlined a conception of heritage in its preamble, declaring: “Imbued with a message from the past, the historic monuments of generations of people remain to the present day as living witnesses of their age-old traditions. People are becoming more and more conscious of the unity of human values and regard ancient monuments as a common heritage” (ICOMOS). Were the early heritage debates in Singapore during the rapid redevelopment of its urban landscape influenced by this Western hegemony, as is suggested by studies of other Asian countries?

Heritage Conservation in Colonial Singapore

The urban redevelopment of Singapore was planned well before the People’s Action Party (PAP) government took over in 1959 when Singapore achieved self-government. These plans do suggest a Western hegemony, in particular, dominating ideas from the center of the British Empire. In 1955, a Master Plan for Singapore, modeled on the Greater London Plan prepared by Peter Abercrombie in 1944, was drawn up by veteran British town planner Sir George Pepler (Lim 1955, column 574). He had been responsible for Britain’s Town and Country Planning Act of 1947, which enacted many of Abercrombie’s ideas (Khublall and Yuen 1991, 40).

The Singapore Master Plan was approved by the Governor in 1958 as a statute that controlled all future urban development until 1972 (Dale 1999, 73–77). It became known as the 1958 Master Plan. Pepler’s main recommendations contained many features of the Greater London Plan. Singapore’s Master Plan promoted decentralization by setting up satellite “new towns” outside the Central Area such as Woodlands, Yio Chu Kang, and Jurong, to facilitate future urban growth rather than add to an already densely populated Central Area. The Master Plan was designed to accommodate Singapore’s doubling of population from one million in 1953 to two million in 1972. Urban redevelopment of Singapore’s overcrowded Central Area was planned. A green belt was envisaged to contain the expansion of the Central Area. All these concepts applied to Singapore had their origins in Abercrombie’s ideas. The planned urban redevelopment of Singapore appears to illustrate notions of a Western hegemony over the cultural and urban landscape during the colonial period.

One of the other recommendations of the plan was that the colonial urban planning agency and public housing builder, the Singapore Improvement Trust, “shall prepare and shall supplement and amend from time to time a list of ancient monuments and land and buildings of historic and/architectural interest” (Colony of Singapore 1955, 17). The Singapore Improvement Trust took on an additional role of “the protection of ancient monuments and land and buildings of historic and/or architectural interest” (ibid.). Thirty historic buildings and sites, all dating before the mid-nineteenth century, were listed by the Master Plan as worthy of preservation. Their selection seemed to follow the then current Western ideas of “authenticity” and antiquity, because no building from the twentieth century was included. However, there were compromises as most of the temples and mosques had undergone substantial restorations since their erection in the nineteenth century.

The list included many temples such as the Thian Hock Keng and the Sri Mariamman temples in Chinatown, built in 1821 and 1827 respectively. Also listed were an equal number of mosques such as the Jamae Mosque in Chinatown, which was first built in 1826. European churches were included, such as the Catholic Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, constructed in 1846, and the Anglican St Andrews Cathedral, built in 1862. Raffles Institution, a school erected in 1837, and Outram Gaol, built in 1847, were also buildings to be preserved. One Indian and two Malay-Muslim graveyards were on the list (ibid.). The list was a multicultural representation of Singapore’s different races and faiths. This was the first time a Singapore state agency had been entrusted with heritage conservation.

The 1955 heritage list of what were called “Ancient Monuments and Land and Buildings of Architectural and/or Historical Interest” did not represent the first compilation of Singapore’s historic buildings and sites. However, it was the first list in Singapore presented by a state agency for future preservation. In 1954, the colonial administration had formed what it called the Ancient Monuments Committee to compile a list of historic buildings and monuments. This list designated sites where historic markers were placed; it was not for protecting sites and buildings, and it did not stop buildings from being demolished (Public Relations Office, 625/54).

The 1954 and 1955 lists were examples of what Laurajane Smith called a situation in which heritage is designated by a “hegemonic discourse” which was “reliant on power/knowledge claims of technical and aesthetic experts” (2006, 11). The committees that drew up the 1954 and 1955 lists also illustrated Byrne’s notion that in Asia, there was a Western and colonial hegemony over what constituted heritage. Both committees comprised mainly colonial officials who were trained in British ideas of what were regarded as historic buildings, monuments, and sites. They included Michael Wilmer Forbes Tweedie and Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, the postwar directors of the Raffles Museum. All items listed were originally erected in the early nineteenth century. Most items on the lists were temples and mosques. Older religious buildings and sites were seen as more “authentic” and “original” representations of Asian cultures (Public Relations Office, 625/54).

The 1955 list was drawn up in consultation with an organization known as the “Friends of Singapore” (Ministry of Culture, 276/63). This society was founded in 1937 by wealthy and well-educated members of the colonial elite in order to “stimulate interest in the cultural and historical life of Singapore” (Straits Times, August 19, 1948). The organization’s founder was European lawyer Sir Roland St. J. Braddell, who had written a history of Singapore (Singapore Free Press, September 10, 1947). One of the society’s objectives was the “preservation of historical buildings and sites” (Friends of Singapore, Charter). European firms held “life membership” in the society in order to financially support the organization. Its patron was Sir Robert Black, the Governor of Singapore (Straits Times, August 26, 1955; January 23, 1957). When the Master Plan became law in 1958 after extensive public meetings on its proposals, two more buildings were added to the list to make a total of 32. These were the Sun Yat Sen Villa in the Balestier Road area and the Sri Srinivasa Perumal temple in Little India.

The Friends of Singapore continued to have considerable influence over the listing of historic buildings. The society was invigorated by the heritage preservation powers of the Singapore Improvement Trust. Previously, the society had failed in its attempt to produce a historic guide to Singapore, and its major achievement was putting up portraits of all of Singapore’s governors in the Victoria Memorial Hall (Singapore Free Press, April 1, 1948). In 1956, the Friends of Singapore supported the Singapore Improvement Trust in resisting objections to the heritage listing of Killiney House at No. 3 Oxley Rise, which was built in 1842 by the Surgeon General Dr. Thomas Oxley. The owner, Chartered Bank Trustee Company, felt that if the building were classified as an “ancient monument,” it would be hard to sell it, so the company wanted it removed from the list. The Friends of Singapore gave the Singapore Improvement Trust historical and architectural “evidence that the property should be preserved for prosperity” (Straits Times, June 21, 1956). Killiney House remained on the list. In the same year, the Friends of Singapore successfully fought to keep a nature park in the Master Plan that marked a 1942 battle between the Malay Regiment and the Japanese, as park space. The army had proposed that it be turned into a car park (Straits Times, June 22, 1956; July 12, 1956).

In 1957, at the Friends of Singapore’s 20th anniversary dinner, its president T. W. Ong, a wealthy Anglophile Chinese businessman, felt emboldened to make the organization’s first clear statement against the demolition of historic buildings: “We should not tear down historical buildings and monuments so quickly in order to put up some new brick and mortar building for it is difficult to replace some monuments” (Singapore Free Press, February 7, 1957). For Ong and the Friends of Singapore, these buildings reinforced the collective memories of the past of the country’s different ethnic communities (Friends of Singapore, Report and Accounts for the Year 1937/38). Ong added: “Singapore would be a city without a soul if the cultures of its various races were not maintained” (Singapore Free Press, February 7, 1957). The activities of the Friends of Singapore demonstrated that in the 1950s, there appeared little difference between preservation and conservation. These terms were as they appeared in the Venice Charter in the 1960s—almost interchangeable. This Western hegemony over the terms of heritage used in Singapore was also evident in the terminology and ideas employed in the redevelopment of the urban landscape, which became a priority in the early postcolonial period.

Urban Renewal and “Rehabilitation” of Historic Areas

This emerging awareness of heritage conservation within and outside of the state threatened to be side-lined by the election of the People’s Action Party (PAP) government in 1959 when Singapore achieved self-government from the colonial administration. The PAP came to power on a party platform promising to create more jobs and to build more public housing (Fong 1980, 72). This entailed what it called “clearing the slums”—demolishing dilapidated old buildings overcrowded with the urban poor in the Central Area of the city of Singapore and erecting modern flats in their place (The Tasks Ahead 1959, 29). The PAP’s 1959 election manifesto declared that “the Colonial Government has failed miserably in housing the people, and the result is more and more slums” (ibid.). The priority of the PAP was that “land can be used fully for housing and industrial development” (ibid.).

Some members of the incoming PAP government evinced animosity towards the Friends of Singapore. Lee Kuan Yew, leader of the PAP and after 1959 the new Prime Minister of Singapore, dismissed the Friends of Singapore as a “quaint” society “whose objects is the entertainment of past and present Governors and one of whose duties is to collect portraits of previous Governors” in order to get what he called “kudos” from the Governor (Lee 1956, column 186). The Friends of Singapore was equally dismissive of Lee. Its president Ong alleged that Lee was engaged in the “distortion of facts to gain personal publicity,” which Ong said, “was not an uncommon trait among leaders of any extremist party.” Ong went even further, adding that Lee was in a position where he “must concoct something to save his own skin” (Straits Times, September 9, 1956). These words were exchanged between Lee and Ong in 1956, but they doomed the Friends of Singapore as an emerging heritage NGO once Singapore’s colonial administration handed power over to the PAP. The Friends of Singapore ceased to have any influence and was disbanded by the 1970s.

After 1959, urban planning in Singapore entered a new stage. In the last few months of the colonial administration in February 1959, legislation was drafted to dissolve the Singapore Improvement Trust into two organizations: the Housing Development Board to build public housing and the Planning Department. The transition to the postcolonial government meant these ordinances did not come into effect until February 1960. However, there were teething problems for the postcolonial government. There was an acute shortage of planning staff in the Planning Department, which consisted of three local urban planners, only two of whom had experience in the Singapore Improvement Trust (Dale 1999, 78). Given the deficiencies of an understaffed, ad hoc, and uncoordinated haphazard planning process, the Singapore government requested assistance from the United Nations Development Programme for recommendations on dealing with the difficult issues of urban renewal and redevelopment. This culminated in several key reports and recommendations that had far-reaching consequences for the Singapore landscape.

The first United Nations mission in 1962, led by Erik Lorange, recommended the complete revision of the 1958 Master Plan in order to pursue redevelopment, large-scale public housing, and the establishment of new towns. Ole Johan Dale (1999, 78), a Singapore-based urban planner, deemed the catalyst which Lorange provided for urban renewal as his “most important contribution.” For Lorange, “the social arguments for taking up central redevelopment of Singapore are evident and obtrusive. The condition of the majority of the central residential buildings is poor to a frightening degree” (Final Report 1962, 6). He concluded that “comprehensive redevelopment without a doubt is the ultimate answer of the present extensive accumulation of slums in the Central Area, but this will demand a long period of years to fulfil in substance” (ibid., 51). Lorange suggested that in the meantime, minor measures be taken to “rehabilitate” areas. According to him, while some buildings might need demolishing, many in the short term could be “subjected to code enforcement, to induce the owners to widen shop frontages and make selective repairs on their buildings” (ibid., 51).

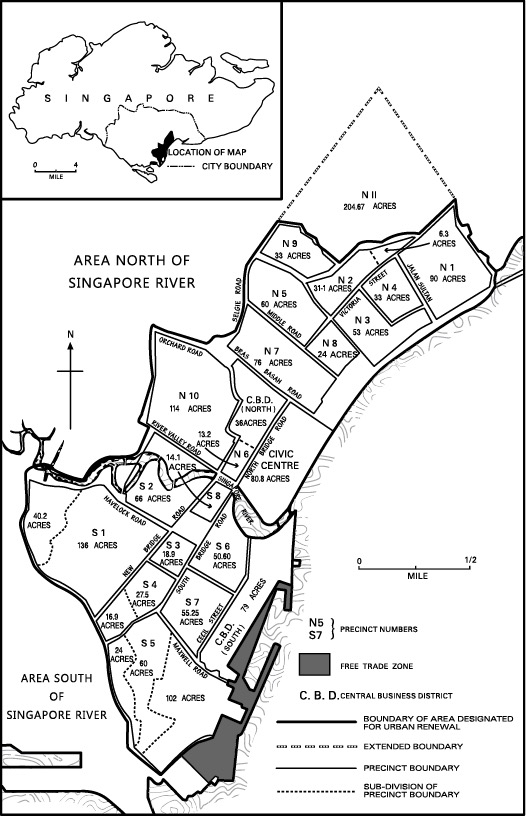

In his report, Lorange recommended that demolition and extensive urban redevelopment begin only from the fringes of the Central Area and gradually move into its center so that much could be learnt from experimenting on the periphery of the old city area. For the first stage of urban renewal, he designated the old Kampong Rochor shophouses that were part of the Malay-Muslim Kampong Glam historic area, extending from Crawford Street to Jalan Sultan. The area had been designated N1 (meaning North 1 precinct) among the 19 precincts in the city divided up by the 1958 Master Plan. While Lorange’s recommendations for urban renewal were accepted by the Singapore planning authorities, his calls for “rehabilitation” were ignored. In 1966, Kampong Rochor, with the exception of the Hajjah Fatimah Mosque, built in 1845, was demolished to make way for public housing as part of the first phase of urban renewal in Singapore. The Hajjah Fatimah Mosque, along what was then Java Road, was on the 1958 Master Plan’s list of historic buildings to be preserved (Gamer 1972, 139). This lone standing historic building in the demolished Kampong Rochor area testified to the power of being on the list of what were regarded as historic buildings. However, at the other end of the Central Area, Outram Gaol, which was also on the same heritage list from the 1958 Master Plan, was demolished along with many shophouses, to make way for the redevelopment of the S1 (meaning South 1 precinct) area in the south, as recommended by Lorange.

A subsequent 1963 United Nations mission consisting of Charles Abrams, Susumu Kobe, and Otto Koenigsberger, also laid the groundwork for intensive state involvement in urban planning. The mission recommended that urban planning in Singapore be institutionalized through the creation of an Urban Renewal Team within the Housing Development Board (Growth and Urban Renewal in Singapore 1963, 189). Set up in 1964, the Urban Renewal Team later became the Housing Development Board’s Urban Redevelopment Department in 1966 and was legislated as a separate statutory authority, the Urban Redevelopment Authority in 1974.

In contrast to Lorange, the members of the 1963 United Nations mission were adamant that urban renewal should not lead to large-scale demolition. Members of the United Nations mission, like Lorange, highlighted that the “three indispensable aspects of urban renewal are (1) conservation, (2) rehabilitation, and (3) rebuilding” (ibid., 121). They “rejected the idea of wholesale demolition of large quarters” of the old city (ibid., 18). They explained that “this decision was motivated primarily by the desire to minimize the social upheaval and the suffering” (ibid.). The decision was “based also on the recognition of the value and attraction of many of the existing shophouses and the way of living, working, and trading that produced this particularly Singapore type of architecture” (ibid.). “Every big city needs escape hatches from sameness and order, and areas like Chinatown can emerge into important examples if they are treated with something more subtly than the steam shovel” (ibid., 123). They warned: “We must beware of the bulldozer ‘addicts’ who are straining to flatten out every hill, fill in every valley, and cover the resulting flat desert with a dull network of roads, factory sheds, and regimented blocks of houses” (Gamer 1972, 142).

According to Alan Choe (1975, 98), who became the first head of the Urban Renewal Department, the 1963 United Nations Mission Report was “studied by the Singapore Government, and subsequently a comprehensive plan for urban renewal in the Central Area of Singapore was formulated.” Choe had absorbed postwar British ideas of town planning and heritage conservation when taking extra electives for his degree in architecture from the University of Melbourne in Australia (Straits Times, April 12, 2014). Urban planners in Singapore during the 1960s, while not accepting rehabilitation and conservation as much as the United Nations teams recommended, did not rule them out. However, in the case of Singapore, urban planners such as Choe tended to be ambivalent about its built heritage:

Unlike England or Europe, Singapore does not possess architectural monuments of international importance. There are therefore few buildings worthy of preservation. In addition many of the buildings in the Central Area are overdue for demolition. Hence to preach urban renewal by conservation and rehabilitation alone does not apply in the Singapore context. There must also be clearance and rebuilding. (Choe 1969, 165)

The comments by Choe about Singapore’s built heritage reveal why in the 1960s the balance between conservation and redevelopment was tilted towards the latter. Western notions of “authenticity” in having a “grand old building” in the same physical state for hundreds of years were difficult to apply to the local landscape. However, Choe believed that the movement towards a list of monuments and historic buildings to be preserved was compatible with urban renewal. In August 1968, when the idea of a National Trust or Preservation of Monuments Board was being mooted within the Ministry of Culture, Choe said in a public address: “As a result of urban renewal it has been found desirable to set-up a proper body to look into the question of ‘Preservation of Sites, Buildings and Monuments of Historical or Architectural Interests.’” He added, “Legislation for the proper formation of such a body will give it the necessary powers including the proper selection, preservation, management financing etc. of such sites, buildings and monuments” (Choe 1968, 3). Choe’s expression of this ambivalence towards the creation of a heritage preservation body was in keeping with the debates that were going on inside the Singapore government bureaucracy during the 1960s. There were discussions about how to create a government agency that could preserve historic buildings amidst extensive urban renewal.

UNESCO and Singapore

While a conservation-redevelopment debate over whole areas of Singapore’s old city was stimulated by the United Nations mission of urban planners, the action of UNESCO also provoked discussion in Singapore over the preservation of its historic buildings, monuments, and sites. In 1961, Vittorine Veronsese, Director-General of UNESCO, wrote to the Singapore Ministry of Culture asking for a representative to be on UNESCO’s International Committee on Monuments, Artistic and Historical Sites and Archaeological Excavations, which was the predecessor of the World Heritage Committee (Ministry of Culture, 179/61). UNESCO was stepping up its activities to help the preservation of monuments in the developing world as well as in developed countries. In Asia, these actions included a 1961 assessment of the Buddhist pagodas of Pagan in Burma, a 1963 restoration study of the giant Buddhist statues at the Bamiyan site in Afghanistan, a 1966 mission to preserve the Buddhist stupas of the old Thai capital of Ayutthaya, a study of the Indonesian site of Borobudur in 1966, and the restoration of Angkor Wat in 1967–68 (UNESCO 1970, 33–36).

The Director-General of UNESCO, while noting national efforts to preserve historic monuments and sites, believed that UNESCO “had a duty to take its own steps to bring these national efforts into a world-wide scheme” (ibid., 23). UNESCO proposed an International Campaign for Historical Monuments in 1964 aimed at creating among UNESCO member nations “publicity during this period, to bring home to their citizens the value of the monuments of the past” (ibid.). UNESCO’s intervention stimulated the idea of setting up in Singapore a heritage preservation organization based on the model which Singapore bureaucrats were most familiar with—the National Trust of England (Ministry of Culture, 400/62).

Christopher Hooi, a senior curator of anthropology at the Singapore National Museum, advised the Singapore government to accept UNESCO’s invitation to participate in its proposed international heritage preservation organization (Ministry of Culture, 179/61). Hooi had graduated with a degree in anthropology from the University of London, and his thinking on the preservation of historic buildings was influenced by his time in Britain when he had familiarized himself with the National Trust and British heritage legislation. His enthusiasm for what UNESCO was planning and his own ideas, which were drawn from his training in Britain, confirms Bryne’s notion that the Western hegemony on early heritage management in Asia was the result not of ideological “imposition” but of “transfer” (Bryne 1991, 273). Hooi was also aware that other developing countries were setting up state organizations to manage historic buildings based on the British Ancient Monuments Protection Act, which dates to 1882. This act also had its own list of preserved and protected historic buildings. Within the developing world, India followed Britain and had its own Ancient Monuments Preservation Act since 1904; following independence, this was expanded and became the 1951 Ancient and Historic Monuments and Remains Act. India’s version of the Britain’s National Trust was enshrined into the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH) (Ribeiro 1990). Malaya enacted its Treasure Trove Act in 1957, which contained some provisions for protecting ancient monuments and historic sites.

The Singapore Government took Hooi’s advice. Hooi convened an ad hoc committee meeting on December 29, 1962 to apply to the Singapore context UNESCO’s ideas on the preservation of historic monuments and sites. Professor K. G. Tregonning and Professor Wang Teh Chao, two academic historians, as well as two representatives from Singapore’s Ministry of Culture attended this meeting. The committee accepted Tregonning’s proposal that “a historical monument” should be defined as “any building 100 years or over in 1962” and “any other building, shrine or monument which in the eyes of the committee has historical value or significance” (Ministry of Culture, 400/62). Tregonning also suggested “the possibility of legislation being made later on to preserve certain historic monuments” (ibid.). At the next meeting of the committee on January 15, 1963, this definition of what was to be preserved was expanded to include historical sites. After its meetings ended, Hooi transmitted the deliberations of the committee to the Prime Minister’s Office, which maintained an interest in heritage conservation at the behest of Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (ibid.).

Creating a National Trust for Singapore

After the committee to examine UNESCO’s proposals on monuments had ceased, Hooi was involved in establishing a further committee within the Singapore Ministry of Culture in May 1963 to re-examine the 1958 Master Plan’s idea of having a list of historic monuments protected by legislation. The terms of reference of the committee were to re-examine the list of 32 historic monuments and sites outlined by the Master Plan and to suggest regulations that would protect them. It was chaired by Tan Jake Hooi, Acting Chief of the Planning Department that had emerged from the dissolution of the Singapore Improvement Trust, the body entrusted with preserving historic monuments. Tan Jake Hooi and his fellow planners dominated the new committee.

At its first meeting on August 26, 1963, the committee began with the assumption that for preserving a building, “age alone should not be a criterion” (Ministry of Culture, 276/63). The committee considered not just preservation but partial preservation of historic buildings, or even the “preparation of measured drawings of the structures concerned prior to their demolition” (ibid.). The members of the committee examining the list of 32 historic monuments and sites outlined by the Master Plan mulled over whether to have public inquiries when planning applications were made that would affect historic buildings. However, the committee, which was dominated by urban planners, rejected this proposal as it would most likely slow down the rapid urban renewal that they were overseeing in the Central Area of Singapore.

Within the committee, the intentions of the urban planners in the Planning Department were articulated by Tan Jake Hooi, the Chief Planner who headed the Planning Department. At the second meeting of the committee, when addressing the task of deciding on a list of historic sites and buildings to be preserved, Tan remarked that “the object of drawing up such a list” was “not to guarantee preservation but consideration of the possibility of preservation” (ibid.).

The position of the planners on the committee was influenced by the Planning Department’s decision to embark upon significant urban renewal of the Central Area. By mid-1963, the Planning Department had begun the demolition of the 1847 Outram Gaol, which was on the original 1955 heritage list of the draft Master Plan. Neighboring blocks of shophouses next to the Outram Gaol were also slated for demolition. This was recommended in the 1962 United Nations Lorange Report. In March 1963, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew started the redevelopment program by laying the foundation stone of two blocks of flats in the Outram area. Lee publicly announced the redevelopment of the Outram area in conjunction with the Kampong Rochor district. Both these redevelopment projects were recommended by Lorange (Straits Times, March 22, 1963). The Singapore government viewed the old buildings of the Outram area as slums and planned to demolish them and build high-rise flats that would accommodate 50,000 people (Straits Times, March 28, 1963).

At its meeting of February 7, 1964, the committee, at the behest of the urban planners, started dropping entries from the list on the pretext that the buildings would cost too much to restore or were not in their original form. The Western hegemonic ideas of “authenticity” were used by Western-educated planners to remove obstacles to urban renewal. The eight which were dropped at this meeting when urban development was in its early stages were: G. D. Coleman’s house, Raffles Institution, Outram Gaol, Victoria Memorial Hall, Sri Sivan temple, Geok Hong Tian temple, Keramat Radin Mas, and Sri Perumal temple (Ministry of Culture, 276/63). The dominance of urban renewal over heritage conservation was highlighted at this meeting by the deletion of Outram Gaol, which was in the S1 precinct that was one of the first areas of the Central Area to be earmarked for urban renewal. It had been marked for demolition the year before in 1963.

When it came to envisaging the type of administrative body to preserve historic buildings, Singapore’s colonial connections meant that the members of the committee turned to Britain for a model of heritage conservation. The National Trust of England was regarded as a model to follow for conservation in Singapore. It was proposed that the executive committee members of a Singapore national trust would periodically visit and inspect buildings that were designated as worthy of preservation and advise their owners on alterations and changes. The proposed trust would acquire historic buildings that were seen as warranting preservation if acquisition was needed. From its first meeting, the committee favored the creation of such an independent trust, which would have the support of the Ministry of Culture, but like its English counterpart, would primarily rely on private donations as well as some grants from the government (ibid.). At its meeting of March 17, 1964, the committee recommended to the Minister for National Development “the setting up of a Trust which would not only advise Government on what monuments, lands and buildings might be worthy of preservation or other measures but also help raise the necessary funds for securing preservation” (ibid.).

The idea of preserving Singapore’s historic buildings and sites began to gather momentum in Singapore’s bureaucracy in the mid-1960s when there was regret, expressed most publicly by the Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group (SPUR) which was founded in 1965, that the urban renewal projects were changing the urban landscape to the detriment of the historical character of Singapore. SPUR consisted mainly of architects such as William Lim and Tay Kheng Soon, but also included professionals and academics such as Tommy Koh and Chan Heng Chee. Bureaucrats, such as Christopher Hooi and Tan Jake Hooi, were also members of the group. SPUR championed a number of issues in urban planning, namely conservation of old buildings, a rail network, traffic control in the city, and the building of an airport at Changi (Naidu 2002, 62–66). It engaged in public discussions, forums, and talks; wrote letters to the press; and made representations to the government.

Speaking for its members in 1966, Edward Wong in a public talk, made clear SPUR’s position on the limits of urban renewal: “Although we are not advocating large-scale urban renewal, we do recognise that a measure of redevelopment is necessary as part of the evolution of any City” (Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group 1967, 21). SPUR agreed with the 1963 United Nations team that “in both urban renewal and urban rehabilitation we have the same three basic processes. They are rehabilitation, conservation, and redevelopment” (ibid.). SPUR, following the same lines of reasoning as the Ministry of Culture committees on heritage preservation, advocated “the selection of buildings or groups of buildings for preservation indefinitely by reason of their historical, architectural or other special significance” (ibid.). Regarding the Central Area, SPUR argued that when “conserving selected buildings in this area our approach should be quite different from that of the Western world whose architectural history is written and taught from noble architectural monuments. We would be however conserving to a large measure vernacular architecture which is no less interesting” (ibid.). SPUR was suggesting that the ideas drawn from Western hegemony over heritage management, with their stress on “grand” old buildings and monuments, were inappropriate to the Singapore urban and cultural landscape, which comprised architecturally modest shophouses and equally modest religious buildings. Its members also seemed aware that this tipped the balance away from heritage conservation towards redevelopment. SPUR advocated having a pilot study in which the focus would be on rehabilitation rather than demolition and rebuilding.

In the mid-1960s, within the Singapore state bureaucracy, some attention was paid to preservation despite the ongoing urban renewal project. The committee established in 1963 sent its report to the Ministers for Culture and National Development, as well as the Prime Minister’s Office, at the end of 1964. It took some time for the report to be digested and the implications of it to be appreciated. Choe recalled, “One day [in 1967] I got a note from Lee Kuan Yew asking: ‘Have we thought about conservation?’ I sent him the folio I prepared. He sent me a note telling me he was very happy to see somebody was thinking ahead to preserve what little we had” (Straits Times, April 12, 2014). In Choe’s memorandum submitted to the Prime Minister on May 18, 1967, he proposed that for the preservation of historic buildings and sites, legislation should be drawn up to establish a national trust for Singapore. The result was that the Prime Minister “endorsed the need to preserve monuments of architectural or historic interest in Singapore” and directed that a committee be set up exploring “the question of forming a trust to undertake this task” (Ministry of Culture, 254/67).

In September 1967, a committee was formed within the Ministry of Culture and assigned with the task of drafting a piece of legislation aimed at creating a national trust for Singapore. There was continuity with the previous committees. Christopher Hooi was the chairman of a new sub-committee that worked towards the setting up of the national trust. Hooi had chaired the 1963 committee, which had concluded that “if the Trust [was] properly empowered, it could act positively” (Ministry of Culture, 276/63).

The 1963 committee members observed that the existing legislation, the Planning Ordinance, only gave the Planning Department “negative” powers at aiding preservation, such as delaying the approval of planning applications “in the hope that Government or other appropriate Authorities could step in” (ibid.). The government could prevent the owner from redeveloping but was not empowered to assume responsibility for ensuring the upkeep of the historic building or to buy it off the owner.

It was agreed among the members of the 1967 committee that a national monuments trust “should be given sufficient powers to assume a positive role” (Ministry of Culture, 254/67). The proposed national trust’s “positive” powers included the role “to advise [the Minister for National Development] on lands, artifacts, sites and buildings which should be listed and preserved as national monuments” and “the ability to acquire and maintain properties to ensure their preservation” (ibid.).

Proposed legislation for a Singapore national trust borrowed heavily from British heritage legislation and the National Trust of England. The British High Commission in Singapore even sent the Singapore committee copies of British town planning laws on heritage preservation and information about its National Trust. The pieces of legislation included copies of the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act 1913, the Ancient Monuments Act 1931, the Historic Buildings and Ancient Monuments Act 1953, and the Local Authorities (Historic Buildings) Act 1962. In drafting legislation for a Singapore national trust, definitions of terms, such as “ancient monuments” and “owners,” were taken from these British acts (ibid.). The definition of “ancient monuments” was a copy of that written in the British Ancient Monuments Act which, according to the Singapore committee, was defined “so widely as potentially to include almost every building or structure of any kind made or occupied by man from ancient to modern times” (ibid.).

The proposed national trust of Singapore, like its British counterpart, was empowered to inspect historic buildings and to take action against owners who neglected or damaged them. Once a historic building or monument was officially gazetted, as in British legislation, there was no provision for that official declaration to be revoked if the owner was unhappy with it. Following the National Trust in Britain, there was provision for acquiring buildings by purchasing them. The national trust of Singapore was also mainly funded by donations rather than the government. It had a small government-funded budget that paid for its small number of staff. Donations were non-existent as Singapore was a developing country with few local philanthropists who were willing to contribute to preserving historic buildings, compared to donors who supported the National Trust in Britain. There was one major contrast between the proposed Singapore national trust and the National Trust in Britain: the British institution was not a government organization, although it was aided by various pieces of legislation.

Singapore’s national trust, when it was publicly announced in August 1969 by Eddie Barker, the National Development Minister, was conceived as a body serving the interests of the state and concerned with constructing a national identity and promoting economic benefits. The action of the government was viewed by the press as “a new move to see to it that landmarks of old Singapore will not just crumble away in forgotten memories” and that such a government body would assuage “the fear that the bulldozer of progress will leave nothing of the old behind in its dash to bigger and better buildings” (Straits Times, August 3, 1969). The urban planners on Christopher Hooi’s committee emphasized the value of a national trust to tourism and its contribution to the development of an identity for a new nation which had only gained full independence in 1965. For them, “this need for preservation was not only significant in the face of the tourism industry” but also “the very basis of a country’s history and heritage and will contribute to the formation of a national identity” (ibid.).

In 1970, Barker introduced to the Singapore parliament a revised piece of legislation for a government body similar to the proposed national trust of 1969 but called instead the Preservation of Monuments Board. This reflected its role as an arm of the state. When introducing the bill, Barker warned that because of urban renewal, “we may wake up one day to find our historical monuments either bulldozed or crumbling through neglect. As a new Singapore is being built, we must not let the worthwhile part of older Singapore disappear” (Barker 1970, column 337). Singapore’s Preservation of Monuments Board was empowered “to preserve monuments of historic, traditional, archaeological, architectural or artistic interest” (ibid.). It could recommend buildings to the Minister of National Development to be gazetted, and it could then acquire these buildings from their owners. The heritage sites which the Board considered were based on those listed in the 1958 Master Plan that had been evaluated and added to by several government committees in the 1960s. The membership of the Board was similar to the various preceding government committees of the 1960s: Urban Redevelopment Department planners, architects, museum workers, government tourism officials, and civil servants. Perhaps with a view to soliciting donations, a wealthy banker, Lien Ying Chow, became the Chairman of the Board.

Preserving Individual Buildings versus Preserving Whole Conservation Zones

The Preservation of Monuments Board’s early gazetting of individual historic buildings for preservation stimulated heritage debates within the bureaucracy and outside it. When it was first publicly proposed in 1969, the expectations of such a body being able to declare conservation zones rather than just individual buildings were raised in the press (Straits Times, August 3, 1969). In 1970, William Lim, an architect from SPUR, echoed this call when he stated in a public address that “much larger areas will need to be conserved for the character of the Central Area to be kept intact. This is necessary to provide our citizens with a sense of environmental and historical continuity, and to allow gradual evolutionary changes to take place in the urban environment” (Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group 1971, 40).

The issue of preserving whole conservation zones was on the minds of the senior members of the Singapore government. In November 1971, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and Lim Kim San, a senior cabinet minister who implemented the PAP’s housing policy throughout the 1960s, discussed what they called “urban renewal and preservation of our multiracial culture and tradition” (Singapore Tourist Promotion Board, TPB/F/72 [A] Vol. I). At the suggestion of the Prime Minister, a Special Committee for Conversion of Selective Historic Sites into Tourist Attractions was set up. Alan Choe of the Urban Renewal Department sat on the committee, together with senior representatives from the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board, the Ministry of Finance, the National Museum, and the Jurong Town Corporation. Choe suggested to the Prime Minister 16 areas for conservation. The committee proposed to the Prime Minister that the Chinatown area of Telok Ayer Street and Smith Street/Mosque Street/Pagoda Street be divided into two projects for conservation to be overseen by the Urban Renewal Department. The two conservation areas in Chinatown were trials for other areas Choe and the committee had selected for preservation (ibid.).

In the discussions on heritage conservation within the bureaucracy, it was initially thought that the Preservation of Monuments Board might be able to go beyond listing only individual buildings and sites and move to proclaiming whole conservation zones. From its first meeting on April 21, 1972, the Preservation of Monuments Board began to use its power to acquire historic buildings. It started by purchasing the Thong Chai Medical Institution, but this purchase soon turned out to be a financial disaster as the Board’s funds were consumed by the high cost of ongoing restoration. The bad experience of owning a historic building meant that the Preservation of Monuments Board never contemplated doing it again. At this initial meeting, the Preservation of Monuments Board had proposed to preserve a whole street—Telok Ayer Street. This street, with its Chinese Thian Hock Keng temple and two mosques, was seen as “a good example to preserve a whole street as a historic landmark” (Preservation of Monuments Board Meeting, May 26, 1972). In August 1972, the proposal of preserving the whole of Telok Ayer Street was shelved indefinitely because the Board’s technical committee reported that “it would be better to concentrate initially on one project at a time to gain experience” (Preservation of Monuments Board Meeting, August 18, 1972). The failure of this proposal to be followed up illustrated the limitations of the powers of the Preservation of Monuments Board. It lacked the resources to preserve a whole street or zone.

The Preservation of Monuments Board struggled to preserve even single buildings and chose buildings that could be preserved at little financial cost to the Board, but which could still be used for their original function. At first, the Preservation of Monuments Board gazetted for preservation mainly religious buildings that remained in private ownership. State buildings were also easily gazetted. The Board avoided gazetting private buildings that did not have a religious function. The religious buildings gazetted by the Board included the Armenian Church, the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, the Sri Mariamman temple, and the Sultan’s Mosque. There was a clear reason behind such a strategy, as V. T. Arasu discovered when he was on the Preservation of Monuments Board—the Board was underfunded, understaffed, and could only buy one building. Even its role to ensure that historic buildings were maintained and preserved was hampered. Arasu recalled:

I asked why only religious buildings, I was told that because if a building is a public building used for religious purposes, then by declaring the building as a monument you do not have to change the use. Then secondly, you do not need to pay any compensation and PMB need not take any responsibility on maintaining the buildings. (Arasu 2000, 238)

The debates about preserving heritage within the Preservation of Monuments Board reflected how its powers and funding could barely cope with preserving individual buildings, let alone administer whole conservation zones, which was clearly beyond its capacity. In 1976, Alan Choe, General Manager of the Urban Redevelopment Authority, which replaced the Urban Renewal Department in 1974, suggested expanding the powers of the Preservation of Monuments Board. On May 27, 1976, at a meeting of the Board, Choe asked on behalf of the Urban Redevelopment Authority for the Board to “consider on a long term basis the basic preservation of rows of houses and/or sections of central area/Chinatown” (Preservation of Monuments Board Meeting, May 27, 1976). Choe was critical of the Preservation of Monuments Board’s efforts, which he argued “had been confined to only designating individual buildings, mainly in the form of religious structures” (ibid.). However, Choe was rebuffed by the rest of the members of the Preservation of Monuments Board, who felt that the underfunded body with little finance could not cope with designating conservation zones. The Finance Committee of the Board strenuously opposed Choe’s proposal, arguing that “in regard to this particular proposal, the Board would be in no position to render financial contribution” (Preservation of Monuments Board Meeting, June 17, 1976). When the full Board met to consider Choe’s proposal, it took the advice of its Finance Committee and decided to reject the proposal, arguing that “should such a project be launched, it would be too big for any one organization to handle alone” (ibid.).

As General Manager of the Urban Redevelopment Authority, Choe determined the course of heritage conservation in Singapore by initiating trial restoration and rehabilitation of groups of buildings and whole streets. In cooperation with the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board, the Urban Redevelopment Authority started with the restoration of the Tudor Court buildings in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Urban Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report, 1975–76, 42). These were Tudor-styled buildings along Tanglin Road which had been built for government staff during the colonial period (Kong 2010, 32). The Urban Redevelopment Authority, under the 1966 Land Acquisition Act, was given extensive powers to compulsorily acquire land and buildings at a low price; they could then sell them to developers at a higher price (Urban Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report, 1974–75, 13–15). It therefore had access to a level of funding and power over land and buildings that the Preservation of Monuments Board did not.

The Urban Redevelopment Authority focused on demolition and rebuilding, arguing that “in our land-short republic it is part of the thrust towards growth and progress, providing not only environmental improvement but also better employment and investment opportunities” (ibid., 7). It was the Urban Redevelopment Authority that tendered out run-down historic buildings to be demolished and replaced with new concrete multi-storey complexes (Urban Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report, 1975–76, 58–70). Then it published before and after photographs highlighting the changes in its annual report as “progress.” The Urban Redevelopment Authority also highlighted its pilot studies that allowed it to acquire and restore historic areas. A row of 17 shophouses at Cuppage Road was restored and refurbished for new businesses in 1976. These restored shophouses were previously retail shops, sundry shops, and a fishmongery, but upon their restoration became antique shops and stores selling local craft and art items (Urban Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report, 1977–78, 58–60). Next to the restored shophouses was the nine-storey concrete Cuppage Complex, which replaced other old shophouses and roadside hawkers (Urban Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report, 1975–76, 31). The Urban Redevelopment Authority was clearly more engaged in the demolition of historic buildings than their conservation during the 1970s.

In its conservation of historic buildings, the Urban Redevelopment Authority had begun to move away from Western hegemonic ideas of preserving “authentically” and had compromised, such that the buildings could be considerably altered, re-used, and adapted to another purpose. This was a step away from the ideas of the Venice Charter and of UNESCO, which had been debated in Singapore during the 1960s.

In 1976, the Urban Redevelopment Authority also restored a row of shophouses along Murray Street in Chinatown. They were transformed into what was called “Food Alley,” which was a food center selling Chinese, Malay, and Indian delicacies (Urban Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report, 1977–78, 31). When commenting on the Cuppage Road and Murray Street projects, the Urban Redevelopment Authority observed:

Preservation of such buildings will serve as nostalgic reminders of our architecture and history and at the same time afford the streaming tourists with a view of the ‘old Singapore’. In this connection, the acid test of URA’s versatility in design would be the rehabilitation of Chinatown which is presently under active study. One of the main considerations in the preservation of this area is to improve the environmental set-up without losing the engaging bustle that is the mark of Chinatown. (ibid., 4)

The Urban Redevelopment Authority under Choe was in the mid-1970s engaged in experimenting with heritage conservation zones on a small scale; it had the objective of creating larger areas for rehabilitation and conservation in the future, such as Chinatown. The first large conservation zone was the Tanjong Pagar area of Chinatown. The Urban Redevelopment Authority had already acquired most of the land and buildings in the area for demolition and rebuilding. But the success of the small-scale conservation projects prompted a rethink that encouraged the Urban Redevelopment Authority to choose conservation in the mid-1980s (Kong 2010, 44).

Out of these early heritage debates of the 1960s and 1970s, there arose distinctive Singapore institutions of heritage conservation which saw conservation divided between the Preservation of Monuments Board and the Urban Redevelopment Authority. The heritage debates within the Singapore bureaucracy had produced the conservation model that would operate in Singapore from the 1980s onwards. The Preservation of Monuments Board gazetted individual historic buildings, monuments, and sites, which were usually religious or government buildings whose management was well within the limited powers of the Board. The Urban Redevelopment Authority filled the gap in heritage conservation that had been identified by Alan Choe, declaring whole conservation zones and restoring them for reuse. Tracing the rise of this Singapore model of conservation using archival documents of the Singapore state confirms Kong’s observation that within the bureaucracy, there had long been advocates of heritage conservation before the large-scale conservation zones were declared by the Urban Redevelopment Authority in the 1980s.

The debates of these early advocates of heritage conservation in Singapore were influenced by a Western hegemony over heritage management. These considerably diminished by the 1980s as Singapore developed its own institutions of heritage conservation. Singapore had rejected the idea of a national trust and had opted for a state agency, such as the Preservation of Monuments Board, that had very limited powers. Also, by placing the power to conserve whole zones in the hands of the very organization that had aggressively pursued demolition and rebuilding—the Urban Redevelopment Authority—conservation in Singapore could never displace redevelopment. Thus, despite these early debates over conservation in the bureaucracy, in the balance between redevelopment and conservation, it comes as no surprise that the focus was on redevelopment. The marginality of the Preservation of Monuments Board in conservation compared to the dominance of the Urban Redevelopment Authority has continued well into contemporary times. Recent heritage debates over the Bukit Brown and Jalan Kubor cemeteries have reflected this marginality, with graves and cemeteries that were once on the 1958 Master Plan list no longer considered to be the concern of the Preservation of Monuments Board but under the control of the Urban Redevelopment Authority, with its emphasis on redevelopment.

Accepted: January 14, 2015

References

Arasu, V. T. 2000. Accession Number 002307/30. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

Barker, E. 1970. Parliamentary Debates Singapore, Official Report, Vol. 29, November 4, 1970, column 337.

Byrne, Denis. 1991. Western Hegemony in Archaeological Heritage Management. History and Anthropology 5(2): 269–276.

Choe, Alan F. C. 1975. Urban Renewal. In Public Housing in Singapore: A Multidisciplinary Study, edited by Stephen H. K. Yeh, pp. 97–116. Singapore: University of Singapore.

―. 1969. Urban Renewal. In Modern Singapore, edited by Ooi Jin-Bee and Chiang Hai Ding, pp. 161–170. Singapore: University of Singapore.

―. 1968. Objective in Urban Renewal. Singapore Institute of Architects Journal 30: 2–5.

Colony of Singapore. 1955. Master Plan Written Statement. Singapore: Government Printer.

Dale, Ole Johan. 1999. Urban Planning in Singapore: The Transformation of a City. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Final Report on Central Redevelopment of Singapore Prepared for the Government of Singapore by Erik Lorange in Capacity of U.N. Town Planning Adviser. 1962, February 1–July 31. Urban Redevelopment Authority Resource Centre, Singapore.

Fong Sip Chee. 1980. The PAP Story: Pioneering Years. Singapore: Times Periodicals.

Friends of Singapore. Charter. Microfilm NL 11216. National Library Board, Singapore.

―. Report and Accounts for the Year 1937/38. Microfilm NL 11216. National Library Board, Singapore.

Gamer, Robert R. 1972. The Politics of Urban Development in Singapore. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Growth and Urban Renewal in Singapore: Report Prepared for the Government of Singapore by Charles Abrams, Susumu Kobe and Otto Koenigsberger, Appointed under the United Nations Programme of Technical Assistance, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 1963. National University of Singapore Library.

ICOMOS, Venice Charter, accessed November 1, 2014, http://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf.

Khublall, N.; and Yuen, Belinda. 1991. Development Control and Planning Law in Singapore. Singapore: Longman Singapore Publishers.

Kong, Lily. 2010. Conserving the Past, Creating the Future: Urban Heritage in Singapore. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority.

Kong, Lily; and Yeoh, Brenda S. A. 2003. The Politics of Landscapes in Singapore: Constructions of “Nation.” Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Lee Kuan Yew. 1956. Singapore Legislative Assembly Debates: Official Report, Vol. 2, September 7, 1956, column 186.

Lim Koon Teck. 1955. Singapore Legislative Assembly Debates: Official Report, Vol. 1, August 24, 1955, column 574.

Ministry of Culture. Ancient Monuments and Lands and Buildings of Historic or Architectural Interests: Committee to Re-examine the List of 32 Items, 276/63. Microfilm No. AR66. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

―. Corresponding Members of the Committee on Monuments Artistic and Historical, 179/61. Microfilm No. AR39. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

―. International Campaign for Historical Monuments UNESCO, 400/62. Microfilm No. AR55. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

―. Preservation of Building of Architectural of Historic Interest, 254/67. Microfilm No. AR82. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

Naidu, Dinesh. 2002. SPUR: An Alternative Voice in Urban Planning. In Building Social Space in Singapore: The Working Committee’s Initiative in Civil Society Activism, edited by Constance Singam, Tan Chong Kee, Tisa Ng, and Leon Perera, pp. 61–68. Singapore: Select Publishing.

Preservation of Monuments Board Meeting Minutes. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

Public Relations Office. Ancient Monuments Committee, 625/54. Microfilm PRO 14. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

Ribeiro, E. F. N. 1990. The Existing and Emerging Framework for Heritage Conservation in India: The Legal, Managerial and Training Aspects. Third World Planning Review 12(4): 338–343.

Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group. 1971. SPUR [19]68–[19]71. Singapore: SPUR.

―. 1967. SPUR [19]65–[19]67. Singapore: SPUR.

Singapore Tourist Promotion Board. Selective Historical Sites into Tourist Attractions. TPB/F/72 (A) Vol. I. National Archives of Singapore, Singapore.

Smith, Laurajane. 2006. The Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge.

Taylor, Ken. 2004. Cultural Heritage Management: A Possible Role for Charters and Principles in Asia. International Journal of Heritage Studies 10(5): 417–433.

The Tasks Ahead: P.A.P.’s Five Year Plan, 1959–1964, Part 2. 1959. Singapore: PAP.

UNESCO. 1970. Protection of Mankind’s Cultural Heritage. Paris: UNESCO.

Urban Redevelopment Authority. Annual Reports.

Winter, Tim. 2014. Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage Conservation and the Politics of Difference. International Journal of Heritage Studies 20(2): 123–137.

Yeoh, Brenda, S. A.; and Huang, Shirlena. 1996. The Conservation-Redevelopment Dilemma in Singapore: The Case of Kampong Glam Historic District. Cities 13(6): 411–422.

Newspapers

Singapore Free Press

Appeal to All Races. February 7, 1957, p. 18.

Clementi Portrait for Victoria Hall. April 1, 1948, p. 5.

S’pore Friends Want Members. September 10, 1947, p. 8.

Straits Times

When You’ve an Opportunity to Improve Your Life, Grab It. April 12, 2014, p. D4.

Looking Back. August 3, 1969, p. 12.

Steps on the Road to Progress. March 28, 1963, p. 10.

Start to Be Made on S’pore Slum Clearance. March 22, 1963, p. 18.

“Friends” to Give Dinner. January 23, 1957, p. 8.

Ong Hits Back: “You Alter Facts for Publicity.” September 9, 1956, p. 4.

Marina Hill “Battle” Is Over. July 12, 1956, p. 1.

Battle for Marina Hill: 1956 style. June 22, 1956, p. 9.

This House with a Past Has an Uncertain Future. June 21, 1956, p. 9.

Friends’ Patron. August 26, 1955, p. 7.

Friends of Singapore Membership. August 19, 1948, p. 5.