Contents>> Vol. 13, No. 3

Digital Political Trends and Behaviors among Generation Z in Thailand

Wisuttinee Taneerat* and Hasan Akrim Dongnadeng**

*วิสุทธิณี ธานีรัตน์, Public Administration Program, Faculty of Commerce and Management, Prince of Songkla University, Trang Campus, 102 Moo. 6, Khuan Pring, Mueang Trang

District, Trang 92000, Thailand

Corresponding author’s e-mail: wisuttinee.t[at]psu.ac.th

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6839-6932

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6839-6932

**ฮาซันอักริม ดงนะเด็ง, Department of Public Policy, Faculty of Political Science, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus, 181 Charoenpradit Rd, Rusamilae, Mueang Pattani District, Pattani 94000, Thailand

e-mail: arsun.do[at]psu.ac.th

![]() https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9666-8149

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9666-8149

DOI: 10.20495/seas.13.3_521

With online media having become influential socially, economically, and politically, there is a tendency for people—especially Generation Z—to engage in political behavior digitally, particularly on social networking sites. The current research is a mixed-method study on 1,000 respondents from a Generation Z sample group in Southern Thailand. The findings show that the sample group relies mostly upon the online media platform X (formerly Twitter) to consume political news, followed by Facebook and Instagram. Most of the respondents have expressed demands for governmental transformation. The Generation Z group display their political behavior by expressing opinions and criticisms to those close to them who are not parents or relatives (friends, lovers, and special persons), sharing their opinions on social networks, or deciding not to express any political views. In addition, the Generation Z group agree that using social networking sites to express political views is rightful, legal, and free for Thai people, as provided in Chapter 3 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand B.E. 2560 and part of the national democracy system.

Keywords: trends, political psychology, political behavior, digital political behaviors, Generation Z

Introduction

When an individual’s beliefs and principles determine their political behavior, it can be considered political expression. Political behavior consists of various political activities that may effect political change. Patterns or trends of political behavior at the personal level may be seen in the form of political participation both nationally and locally, such as the behavior of political leaders, voting in elections, assisting in political parties’ campaigns, running for election, engaging in demonstrations against the government, choosing a political party to support, and selecting a political ideology (Campbell 2013; Dimitrova et al. 2014; Jati 2020). In the Thai elections on May 14, 2023, it was found that many political parties used social media to communicate with their target audiences. In a nutshell, values shape political behavior, which is a form of political expression at the individual level (Purawich 2023).

Undoubtedly, globalization and the driving force of technology have had a significant impact on social values. The same is true for political behavior. Globalization and technology have transformed political behaviors such as posting messages to express opinions about government policies, accessing political opinions online, and criticizing the work of the government. These forms of behavior are regarded as democratic political participation. In addition, politicians and political parties use digital technology as an open communication channel for publicity purposes, both to push their general agenda and during special occasions such as elections and political campaigns (Ahmad et al. 2019). On the other hand, political expression may have darker consequences such as inequality, division, and exploitation. Its results may further extend to dangers such as cybercrime, cyberterrorism, and cyberwarfare, which involve not only the hacking of information systems but also the disruption of weapons and national defense systems, espionage, and the dissemination of fake news, such as seen in the UK referendum to leave the European Union and the 2016 US presidential election. When it comes to political content, the Internet is still mostly wide open (Gibson et al. 2005).

Due to the easy accessibility of various social media platforms and websites, there are several channels through which government policies can be criticized. And politicians themselves utilize social media to communicate with their target groups. Therefore, political behavior via social media is a topic of interest to many. It is easy today for people to express their political views digitally, especially those in Generation Z, who were born between 1995 and 2015. This generation is regarded as a group who grew up with abundant resources and have the ability to use technology and learn quickly. They also tend to have been raised in nuclear families. In addition, people in Generation Z tend to be addicted to the online world (Sen and Murali 2018, 1–5). Therefore, when it comes to social drive, this group of people emphasize equality and a way of thinking that encompasses all groups of people in all aspects. These individuals want everyone to feel equal regardless of age, ethnicity, or gender. They also wish to be at the center of innovation, feel constantly challenged, and develop themselves for new problem solving. They are not easily satisfied, which can lead to a lack of self-respect. They do not confine themselves to a specific definition, which gives them freedom and a desire to learn and experience new adventures while gradually growing into themselves. Thus, they have different identities, but they do not see these differences as reason for conflict. Generation Z people are generally prepared to place themselves in new encounters, and they tend to understand people and situations that are different (Cho et al. 2020; Farrell and Tipnuch 2020).

A range of nonverbal cues, gestures, and actions have become part of Gen Z’s means of expressing opinions (Suthida 2019). Popular social media case studies in Thailand involving Generation Z individuals between 15 and 18 years old have included them tying white bows, running, singing the song “Hamtaro,” and raising the three-finger salute while singing the national anthem (Khemthong 2020; Phattarapan and Karisa 2023; Phrakhrusamusuwan 2023). When groups of Gen Z individuals from various institutions organize flash mob activities to demand democracy, at certain points participants sing “Hamtaro” with modified lyrics. Youth groups have adapted the lyrics of the song to parody the government. In the modified lyrics the favorite snack is no longer sunflower seeds, and Hamtaro is not just sleeping everywhere. At one point the lyrics state, “Come out and run, run Hamtaro, wake up from your den, run Hamtaro, the best snack is . . . the public tax” (in Thai: “Aow . . . aok ma wing wing na wing na Hamtaro tun aok chak rang wing na wing na Hamtaro Khong aroi teesud kor ku pasi prachachon เอ้า ออกมาวิ่ง วิ่งนะวิ่งนะแฮมทาโร่ ตื่นออกจากรัง วิ่งนะวิ่งนะแฮมทาโร่ ของอร่อยที่สุดก็คือ . . . ภาษีประชาชน”). Such behavior does not necessarily indicate a lack of respect or an unwillingness to acknowledge the sanctity of the Thai national anthem, as perceived by the older generation. It has become increasingly clear that the three-finger salute originated from certain individuals within the group, and it reflects sentiments toward fundamental institutions that Thai people love and cherish (PhraNatthawut et al. 2022). Such behavior diverges from that of previous generations, who were taught that the national anthem was sacred and should be sung with respect, and that individuals were expected to stand upright with composure while it was being sung (Phattarapan and Karisa 2023). Even political rallies have changed, from predominantly offline events to online gatherings; in addition, communication is increasingly done through online platforms (Attasit et al. 2022).

Based on demographic data from 2023, Generation Z made up Thailand’s largest population group, 26.5 percent; baby boomers accounted for 18.7 percent, Gen X 23.2 percent, and Gen Y 21.8 percent (Thailand, National Statistical Office 2023). Thus, Generation Z will be important in the country’s economic and social development over the next twenty years since they will be of working age (Thailand, Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council 2020).

In Southern Thailand, where people take politics seriously, politics is shaped by a combination of broad public politics—akin to a coffee council, where people sit around and talk about politics in a lively way—and open criticism of the work of national and local governments (Chareon 2018, 20). The southern region continues to have long-standing unrest and smoldering conflicts despite persistent efforts by the government to resolve these problems. From the perspective of youths in the area, they also desire a resolution and thus place great importance on political awareness and expression (Adizin 2017; Attasit et al. 2022). Political expression today is not limited to older age groups; Generation Z are also interested in and critical of the government’s work: fighting for justice (Khemthong 2020); dynastic democracy, which often leads to corruption; nepotism (Kritdikorn 2023, 375); the need for politicians who genuinely work for the people; and so on. Therefore, if Generation Z have political ideologies or behaviors that are inappropriate or unproductive, it could potentially impact the future direction of Thailand. In the May 2023 election the Future Forward Party emerged victorious, gaining widespread support despite being a relatively new political party. Many scholars have attributed this success to the party’s policies and the favorable image of its candidates, which resonated well with the younger generation (Phattarapan and Karisa 2023; Purawich 2023). However, in the end the Future Forward Party could not successfully lead the formation of a government because it did not pass the vote in the joint session of Parliament in two rounds. This was due mainly to its attempt to revoke Article 112 of the criminal code, which deals with offenses against the Thai monarchy—an extremely sensitive issue in Thai society (Phrakhrusamusuwan 2023).

Generation Z use social media—Facebook, Instagram, X/Twitter, Clubhouse, and many more platforms—as an important tool for expressing opinions. They account for 27.8 percent of the population in Thailand’s southern region (Thailand, National Statistical Office 2023). Thus, the behavioral model and approach for promoting constructive digital political behaviors among Generation Z in the South becomes an intriguing political arena to investigate. There have been studies on various aspects of Generation Z behavior (Wanwilai 2019; Parin and Jirawate 2020), such as their good organizational membership behavior (Nuchchamon et al. 2019), work behavior (Chenin 2020), and media exposure behavior (Pongsavake 2019). However, there is still a lack of research on the digital political behavior of Generation Z, which is believed to be a crucial issue in the current environment because various events arising from such behavior reflect the mental vulnerability of children and youths in this group. Therefore, this research aims to (1) study trends of digital political behaviors among Generation Z, and (2) compare Generation Z’s digital political behaviors in various categories.

Literature Review

Theoretical Basis of Political Psychology

Political psychology is a cross-disciplinary field that focuses on the study of politics, politicians, and political behavior through a psychological lens. It delves into psychological processes within sociopolitical contexts. The association between politics and psychology is viewed as reciprocal: psychology serves as a tool for comprehending politics, while politics serves as a tool for understanding psychology (Carmines and Huckfeldt 2003). As an interdisciplinary domain, political psychology draws insights from various fields, including anthropology, economics, history, international relations, journalism, media, philosophy, political science, psychology, and sociology (Mols and ’t Hart 2018).

Political psychology aims to grasp the intricate connections between individuals and their surroundings with respect to beliefs, motivations, perceptions, cognition, information processing, learning strategies, socialization, and attitude formation. It examines how psychological factors influence political behavior, attitudes, and decision-making processes at both the individual and collective levels. This interdisciplinary field seeks to understand the psychological processes that shape political opinions, ideologies, leadership, voting behavior, and the dynamics of political groups (Cottam et al. 2010; Huddy et al. 2023). Theories of political psychology are used by political scientists to study and understand political behavior, to understand beliefs, attitudes, cognition, perception, motivation, emotions, and socialization and why people behave the way they do in political contexts: how they engage in political behavior, make voting decisions, or exhibit leadership behaviors. Political behavior encompasses the behavior of leaders as well as other individuals (Dimitrova et al. 2014).

Theoretical Basis of Political Behavior

Political behavior encompasses a combination of democratic attitudes and orientations that recognize individuals as crucial contributors to the advancement of democracy (Coleman and Norris 2005; Campbell 2013; Lidén 2015). It includes formal political participation as well as extra-parliamentary activism. Formal political participation includes voting, having the right to contest for any office or position at the state or national level, and membership in political parties, pressure groups, civil societies, labor unions, market unions, and humanitarian advocacy groups. Extra-parliamentary activism includes protests and unconventional forms of political engagement such as strikes, demonstrations, petitions, and rallies in order to attract attention to the electorate’s most pressing demands and needs regarding government policies for the benefit of the general public (Ruqayya et al. 2022).

Through synthesizing documents and related research, this study concludes that political behavior has three components: political observation, political participation, and political partnerships (see Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1 Key Components of Political Behavior

| Component | Details | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Political Observation | Following political news, political policies, government performance, and behavior of polit icians; discussing politics with surrounding people; and showing interest in political activities | Campbell (2013); Bronstein and Aharony (2015); Mols and ’t Hart (2018); Saksin et al. (2019); Ruqayya et al. (2022) |

| (2) Political Participation | Exercising the right to vote, persuading others to choose candidates that one supports, persuading others to vote, attending speeches by politicians, and disseminating political news | Coleman and Norris (2005); Hatemi et al. (2009); Somit and Peterson (2011); Saksin et al. (2019); Ruqayya et al. (2022) |

| (3) Political Partnerships | Expressing opinions about political policies, making political demands, becoming a member of a political party or organization, running an election campaign, attending meetings of political parties, offering financial support for a political party, fundraising for a political cause, cooperating with government officials in policy implementation, participating in political protests, nominating candidates for political elections, and holding political positions | Hatemi et al. (2009); Campbell (2013); Bronstein and Aharony (2015); Lidén (2015); Mols and ’t Hart (2018); Taufik Alamin et al. (2020); Kanokrat (2022) |

Source: Wisuttinee and Hasan Akrim

Sociopolitical change is inevitable, and sociopolitical phenomena are dynamic and open to interpretation. Individual behaviors are connected with larger societal processes: the dynamics of political behavior, along with the conditions influencing them, are manifestations of broader social changes (Taufik Alamin et al. 2020). Therefore, studies on political behavior often incorporate social and cultural contexts.

Theoretical Background of Digital Politics

Åke Grönlund (2003) and Stephen Coleman and Donald Norris (2005) stated that “digital politics” is the use of information technology to advance democratic processes and structures. The above definition is consistent with Gustav Lidén’s (2015) explanation that digital politics is the use of information technology in political processes involving information, debate, and decision. In other words, digital politics is the use of information technology to exchange information and accommodate political debates and decisions in virtual form on various platforms.

There are two important components of digital politics: (1) the use of information and communication technology, and (2) citizen participation. Relevant entities such as the government, representatives, media, political parties, interest groups, civil society organizations, international organizations, citizens, and voters use information and communication technology to enhance civic engagement (Veera 2016). Roman Gerodimos (2005) identified four components of citizens’ participation in digital politics: (1) accessibility, in which citizens have access to information and communication technology equally and universally; (2) political participation with a sense of attachment, in which citizens are motivated, confident, and well versed in politics, leading to a historical connection and political participation with a sense of commitment and genuine willingness; (3) consultation, in which citizens with differing viewpoints and ideas can meet and discuss issues with the aim of finding a common solution; and (4) linkage between the government and citizens, with the government opening communication channels to listen to criticism, opinions, and suggestions from the public in the policy process.

Research on digital politics is something that scholars prioritize in order to explain patterns of transformative digital phenomena in politics. For example, Sahana Udupa et al. (2020) conducted a study on digital politics in “millennial India.” They proposed that members of millennial India (those between late Gen Y and early Gen Z) shed light on digitalization as a distinct sociopolitical moment, bringing forth new conditions of communication, and explored the significance of millennials who turn to digital media to express political concerns. Digitalization has contributed to the democratization of public participation, facilitated by the self-driven engagement of online users. From research conducted in 38 African countries, it was found that Internet usage and democracy were highly interrelated (Evans 2019). The findings suggest that at the macro level, Africa is moving toward a new stage where the Internet will lead to increased levels of democracy and digital politics. In the case of Thailand, it has been observed that despite government attempts to control inappropriate websites and the flow of information, there is increased political activism among youths using online media (Kanokrat 2022).

Methodology

Research Context

The multi-stage random sampling method was used to determine the research area. Step 1 was to conduct stratified random sampling in the four geographic regions of Thailand identified by the Ministry of Interior: the Northern, Central, Northeastern (Isan), and Southern regions. Based on the results, the South was identified as having relatively high political participation by the Gen Z population. Step 2 was to apply cluster random sampling according to provinces in the Southern region and divide the provinces into three groups: (1) Andaman coastal southern provinces, (2) Gulf of Thailand southern provinces, and (3) southern border provinces. The research context was to determine the area for data collection by selecting a province that met the following requirements: (1) a large number of people in Generation Z as a percentage of the total population, and (2) a large number of people in Generation Z who were interested in politics and wanted to get involved. Thus, the following provinces were identified as target areas for the study: (1) Trang Province (southern Andaman coast), (2) Nakhon Si Thammarat Province (southern coast of the Gulf of Thailand), and (3) Pattani Province (southern border). Step 3 was to apply simple random sampling.

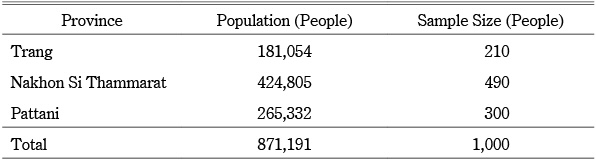

Respondents

To analyze the population, data from the National Statistical Office (2023) pertaining to Generation Z in the three target provinces—Trang, Nakhon Si Thammarat, and Pattani—was used. These provinces had a total of 871,191 people, and stratified random sampling was used to obtain a sample group of 1,000 people representative of each targeted province (see Table 2). The simple random sampling method was used to choose samples based on the following criteria: (1) individuals domiciled in the target area, (2) individuals aged between 18 and 28 years, and (3) individuals with the ability to communicate in Thai. If an individual failed to meet any of the above criteria, they were not considered for the questionnaire and a new individual was randomly selected.

After obtaining quantitative data on the digital political trends and behaviors of Generation Z, qualitative research was conducted via in-depth interviews with this group of people who engaged in driving political activities on digital platforms. A group of 30 informants was selected through purposive sampling, with the following selection criteria: (1) individuals domiciled in the target area, (2) individuals aged between 18 and 28 years, (3) individuals who played a role in driving political activities on digital platforms, such as expressing opinions about political policies, submitting a political demand, being a member of a political party, participating in election campaigns for candidates, and many more.

Research Instrument

Concepts, theories, and relevant research results were considered to form and develop a conceptual framework and research instrument. The tools used in the study were a questionnaire and interview.

Data Collection

Initially quantitative research was carried out, using the survey research method through a questionnaire, as a large sample was required in order to generate a comprehensive summary of information, including the opinions of people in the sample. Subsequently, qualitative research was conducted by delving into important findings from the quantitative research and further analyzing information from members of the target group who were specifically selected as Generation Z people involved in driving political activities on digital platforms, in order to obtain in-depth information on the reasoning behind trends of digital political behavior.

For data collection, the researchers ensured that all ethical guidelines and principles for human research subjects were strictly followed. Before initiating data collection, the researchers went through the Human Research Ethics Review process in order to seek approval from the Center for Human Research Ethics Committee, Social and Behavioral Sciences, Prince of Songkla University. Once approval was granted, the questionnaire and interview form could be distributed to collect data (Certification Code: PSU IRB 2021-LL-Cm028).

With regard to the rights and confidentiality of informants, a research invitation letter was distributed with details about data collection and an informed consent form if the informants agreed to participate. This was to ensure that the privacy and confidentiality of informants was protected. Upon the completion of data analysis, the raw data provided by informants was destroyed immediately; this was carefully handled, as it is a fundamental right of informants to be protected.

Data Analysis

For quantitative data analysis, data that had already been tested for completeness was entered into a statistical package program. The statistics used in data analysis consisted of descriptive as well as inferential statistics. The differences were compared using a multiple comparisons test tool to investigate the levels of opinions and digital political behavior of the Generation Z group classified by general characteristics, together with an application of the least significant difference method to determine differences in pairs of means at significance levels of 0.05 and 0.01.

For qualitative data analysis, after completing interviews with all 30 informants, the researchers transcribed the tapes word for word and cross-checked for accuracy by listening to the audio recordings again, ensuring clarity and addressing any unclear or missing information. The data providers were coded and divided into two groups: students (S) and employees (E). The three research provinces were coded as Trang (T), Nakhon Si Thammarat (N), and Pattani (P). For example, “ST” means “student from Trang.” Content analysis was used for data analysis.

Results

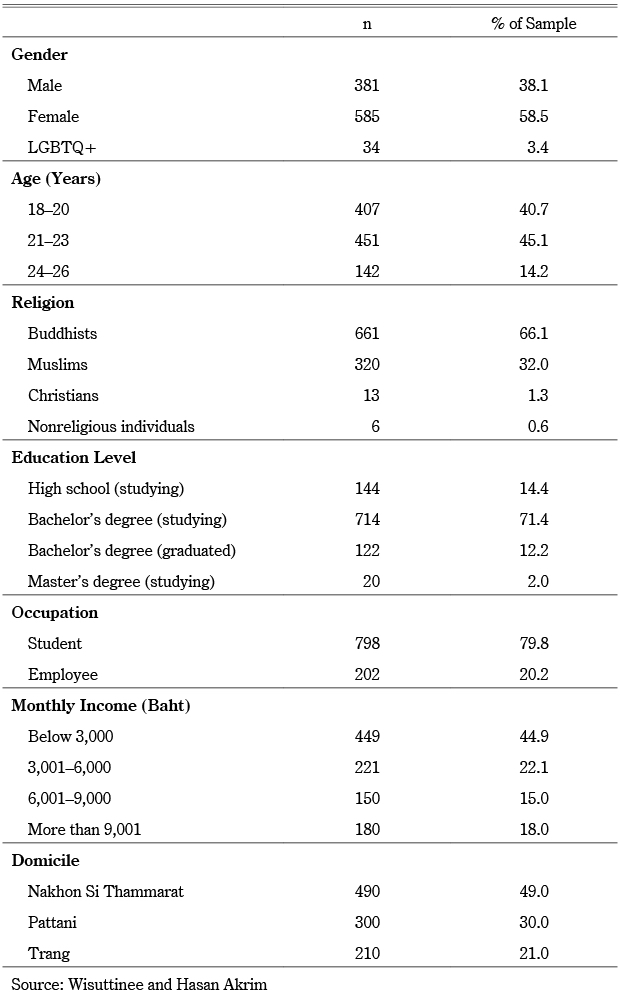

General Characteristics of Respondents in Quantitative Study

The general characteristics of the Generation Z individuals in the sample of 1,000 people were that more than half were female (58.5 percent), followed by male (38.1 percent) and LGBTQ+ (3.4 percent). The general characteristics of the respondents can be found in Table 3.

Table 3 General Characteristics of Generation Z Group (N = 1,000)

Background Information on Respondents in Qualitative Study

The key informants consisted of students and employees who engaged in driving political activities on digital platforms. Most of them were women aged between 19 and 26 years. The respondents had education levels ranging from currently studying in high school (14.4 percent) and pursuing a bachelor’s degree (71.4 percent) to graduating with a bachelor’s degree (12.2 percent) and currently pursuing a master’s degree (2 percent).

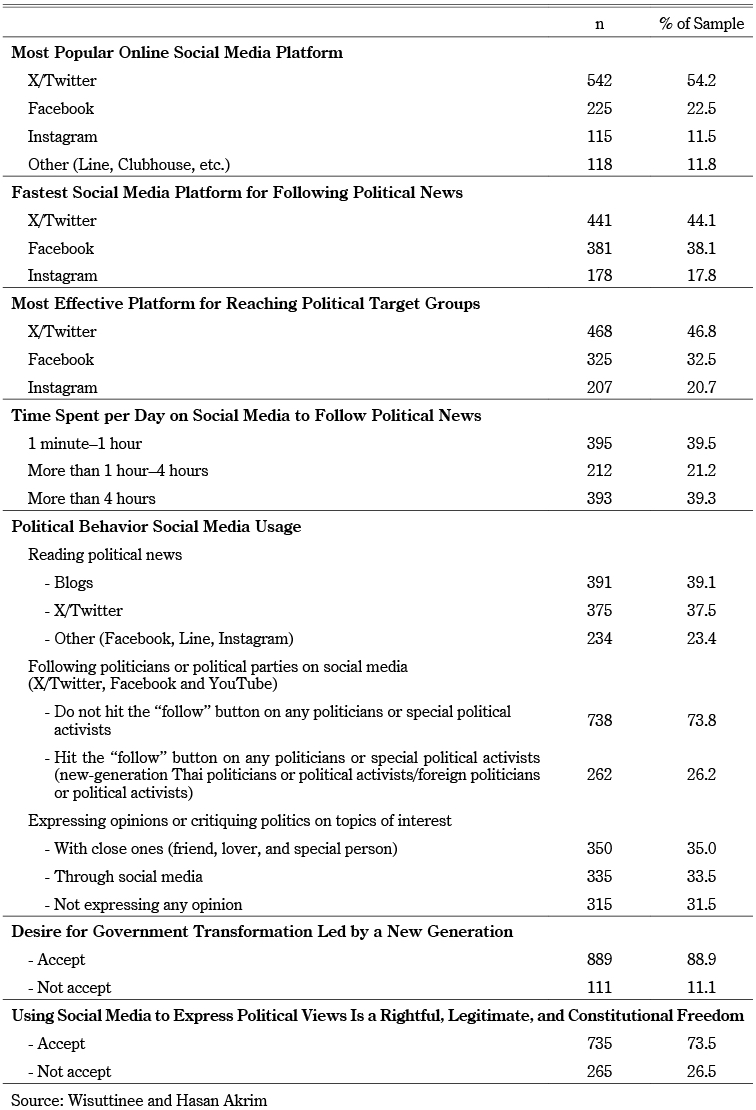

Behavior of Generation Z in Political Media Usage

Most of the respondents used X/Twitter (54.2 percent) to keep up with political news online. Facebook (22.5 percent) and Instagram (11.5 percent) came in second and third, respectively. The behavior of the study sample can be found in Table 4.

Table 4 Behavior of Generation Z with Regard to Political Media Usage (N = 1,000)

Level of Digital Political Behavior of Generation Z

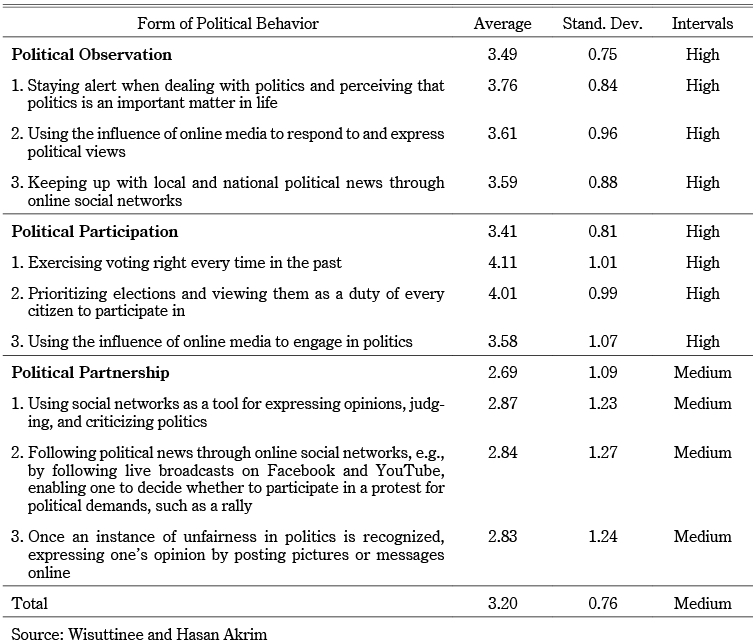

The average and standard deviation of the digital political behavior of Generation Z are at moderate levels (A = 3.20, SD = 0.76), where political behavior in the form of political observation (A = 3.49, SD = 0.75) has the highest average, followed by political participation (A = 3.41, SD = 0.81) and political partnership (A = 2.69, SD = 1.09), respectively. Table 5 summarizes the descriptive statistics.

Table 5 Digital Political Behaviors among Generation Z Group (N = 1,000)

Based on in-depth interviews, an interesting phenomenon was observed in the online media usage behavior of Generation Z: Generation Z individuals often create new accounts or choose to join closed groups to express their political opinions, as the expression of such opinions in Thai society is still restricted, even with family and friends. Some student interviewees gave the following explanations:

“I chose to create another Facebook account specifically for expressing political opinions. I did this to avoid having to answer questions and to avoid problems with my parents and close friends. I think politics is still a relatively sensitive issue in Thai society.” (SN1)

“Adults usually think that I am arguing and showing aggressive behavior, even though in reality I just want to express my own opinion only.” (SP5)

“I know that my parents, grandparents, and I have different political preferences. Therefore, we choose not to discuss this matter with each other.” (ST2)

The above statements are consistent with the comments of Generation Z employees who were interviewed:

“When I want to express my political opinions, I choose to use Twitter over Facebook or IG because some of my parents and my boss may not use it. The main reason is that I choose to only let my friends or close ones see the parts of me that I want them to see. Because I don’t know how people will feel when we express our political opinions.” (ET2)

“In the workplace, expressing political opinions is a sensitive issue that requires special caution.” (EN3)

“In the working world, everyone must show maturity. Therefore, giving importance to political behavior is crucial.” (EP4)

Thus, to express their opinions freely with like-minded people who share the same perspective, Generation Z often choose to comment only on things that others want to hear about and discuss, even if it goes against their own thoughts and beliefs.

“I want there to be a reform in the country. I’m tired of politicians who deceive the nation, tired of the political system, and tired of the current state of Thai society. However, I can’t discuss these matters with my parents or colleagues close to me. That’s why I choose to have a presence in the online world instead because I feel a sense of freedom, and this is my safe zone.” (EP5)

“I have to pretend to support a politician whom my parents admire, even though in reality my feelings are opposite. Because I hardly see that politician doing anything beneficial for our province.” (ET4)

“The expression of differing opinions is something that cannot be openly revealed in Thai society.” (EN1)

“I’ve heard that some of my long-time friends are in disagreement due to differing political views. I don’t want to be caught up in that kind of situation, so I choose to express my opinions in a closed group where people share similar interests instead.” (SN3)

“I’m also one of those who choose to speak about things that others want to hear, even though I may not agree with the truth.” (ST3)

“Thailand should reach a point where everyone is free to express their true political opinions without reservation.” (SP4)

Results of Objective 2: Comparison of Digital Political Behaviors Classified by General Characteristics of Generation Z

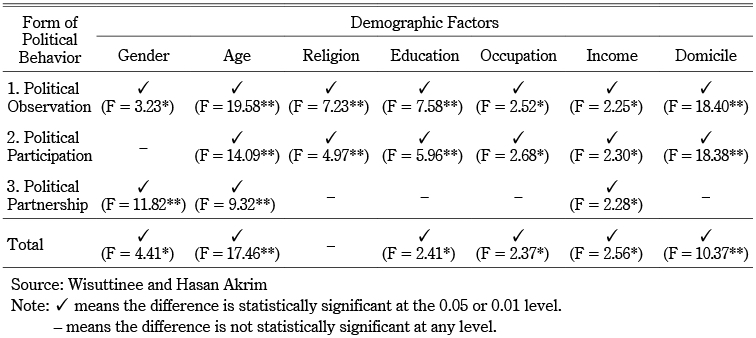

This study analyzes the forms of Generation Z’s digital political behaviors, comparing these forms across various demographic factors: gender, age, religion, education level, occupation, income, and place of residence. Differences in the digital political behaviors of Generation Z are statistically significant at the 0.05 and 0.1 levels. With regard to political observation, the views of Generation Z with clearly different digital political behaviors are ranked the highest, followed by political participation and political partnership, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6 Comparisons of Generation Z’s Digital Political Behavior, Classified by Demographic Factors

Discussion

Discussion of Research Objective 1:

The world is going through major political, economic, and social changes, with technology playing a big role. Political behavior has changed with the proliferation of digital technology, evolving into “digital political behavior.” Particularly Generation Z, who have grown up with a variety of technologies, are familiar with all forms of digitalization (Dolot 2018; McCann Worldgroup 2022). They use technology with such agility that it is almost part of the body (Kununya 2022). No matter what information this group needs, it is usually available online (Farrell and Tipnuch 2020; Klinger 2023).

Political observation means becoming politically aware and realizing that politics is an important part of life. This is something the new generations care about. With the Thai government regulating the flow of information, Generation Z Thai have become more politically conscious, regarding politics as a crucial aspect of life. This has had an impact on political movements in various forms (Kanokrat 2022). Interestingly, the results of this study show that political opinions can still not be freely expressed, even though Thailand has a democratic government. Generation Z have found a solution by expressing political views through various forms of online media (Gidengil et al. 2016). They are comfortable using technology and are more likely to be exposed to a variety of political views online. They are also less likely to fear reprisals from their parents, their friends, or the government, while some may choose to express themselves by being silent and not expressing any opinion at all (Miller 2016; Sen and Murali 2018; Attasit et al. 2022).

Political participation: Thailand had its first constitution (Provisional Governing Constitution Act of Siam, B.E. 2475) in 1932. It has been governed as a democratic system with the king as the head of state for almost a century. But within the Generation Z group there is a perception that the country is not a democracy: they see that the government has not granted full freedom to the people, especially during the administration of General Prayuth Chan-o-cha, spanning more than eight years. Therefore, Generation Z place great importance on elections, as can be seen from the elections on May 14, 2023. Voter turnout was as high as 75.71 percent (Thailand, Office of the Election Commission of Thailand 2023), which is believed to be the highest proportion of eligible voters ever recorded. This indicates the interest and enthusiasm of the public in exercising their rights, not just as a civic duty specified in the constitution but as an expression of the desire for change through the electoral process. It also reflects the power of social media, which played a role in shaping the perception and political participation of the public both before and after the elections, including during the political party campaigning period. Social media is considered a crucial tool that helps drive election trends and at the same time has transformed the political landscape from traditional paths. It has enabled the emergence of “natural canvassers” and conversations about political change through Twitter hashtags, as well as information dissemination through various other platforms (Purawich 2023).

Political partnerships: The Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2560 (the twentieth and current constitution) stipulates in Chapter 3, Section 34, the rights and freedoms of Thai people to express their opinions and rightfully criticize the government’s work; thus, such behavior is legal within the framework of the constitution. Such rights are also consistent with the provisions of Section 9 of the Official Information Act, B.E. 2540, which stipulates that government agencies have a duty to provide official information for the public to access and assess, such as policies, plans, and projects; annual expenditure budgets; duty manuals or instructions for government officials that affect the rights and duties of the people; and concession contracts. Therefore, Generation Z in Thailand perceive Section 9 of the Official Information Act, B.E. 2540 as sanctioning a form of political behavior that includes expressing opinions, making judgments, and criticizing politics through online media (Turner 2018). However, the reality is the opposite, as the government has historically restricted various forms of political behavior. As a result, Generation Z express themselves symbolically in various ways such as tying white bows, running, singing “Hamtaro,” and raising the three-finger salute—all of which have become viral trends across online platforms (PhraNatthawut et al. 2022; Phattarapan and Karisa 2023).

Despite a growing trend toward openness in political behavior, particularly among Generation Z youths, such behavior might still be seen as bold or disrespectful because there are cultural and societal norms that discourage or frown upon certain forms of political expression, especially from the younger generations (Nawapon 2022; PhraNatthawut et al. 2022; Phrakhrusamusuwan 2023). Therefore, it is essential for the government and policymaking agencies to adjust perceptions toward the older generations and foster an understanding of the differences between generations. Recognizing such differences does not equate to passing judgment. Since older individuals often have an influence over Generation Z, there may be a need to establish constructive avenues for expression, providing space for Generation Z to express themselves freely within appropriate boundaries (Attasit et al. 2022; Kanokrat 2022).

Discussion of Research Objective 2:

Gender: Gender equality is a popular topic of discussion around the world. It is one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a set of global development goals endorsed by the 193 member states of the United Nations (United Nations 2023). Thailand’s Gender Equality Act, B.E. 2015 (Thailand, Secretariat of the Cabinet 2015) was enacted as an alternative to protect and preserve the rights of people who are treated with unfairness and discrimination while promoting equality between men and women as well as people of diverse genders. This was Thailand’s first legal instrument for protecting gender diversity (Section 3 of the constitution) and came into force on September 8, 2015.

Generation Z is a truly diverse group, both in terms of gender and in terms of acceptance of gender differences (Howe et al. 2008; Hatemi et al. 2009; Gil de Zúñiga and Chen 2019). Although Thailand has a law on gender equality, there are still many concerns that remain to be addressed, such as marriage equality (Jirayut and Nakorn 2020) and change of title in official documents to match gender change (transgender). Marriage equality and marital rights is regarded as a crucial issue in Thai society, particularly among Generation Z. This is evident from past Thai elections, where it was used as one of the key policies to garner support by several political parties, including the Pheu Thai Party (Sudarat 2023), which was a leading force in the formation of the current government. In fact, many countries have already enacted marriage equality laws—the Netherlands, Belgium, Brazil, the United States, the Republic of China, and many more.

Age: There is empirical evidence that Thailand’s Generation Z—youths, adults, and working-age people—place importance on political behavior through the use of online media. This is considered a positive phenomenon as it indicates they are paying attention to the unfolding of their own political situation and expressing themselves in a way that differs from the past, when political behavior took offline forms such as protesting in front of democracy monuments (Somkiat 2022; Kasit 2023). Thus, in the past political behaviors were typically limited to certain groups of people. However, digital technology has broken down barriers, making political expression easier and convenient for more people (Khemthong 2020; Attasit et al. 2022). On the other hand, digital technology has also created a more vulnerable group: while Generation Z are adept at using digital technology across various platforms, they lack the critical thinking skills to effectively filter information. When there is a discrepancy between the reality and the group’s understanding of political issues, it may lead to inappropriate behavior that can spread and have a wide impact. This is because Generation Z pay attention to equality, do not confine themselves to a specific identity, and are independent and keen to learn and take on new challenges. Therefore, if there is any issue Generation Z disagree with or view as incorrect, they are ready to protest in order to make their point (Sen and Murali 2018). Sensitive social issues, such as those related to institutions, politics, beliefs, and traditions, carry a higher risk of creating problems. When such sensitive issues are misunderstood or misrepresented, it can lead to heightened tensions and potentially result in conflicts within the community or society at large (Kritdikorn 2023).

Religion: The teachings of all religions are aimed at cultivating good individuals. As for the digital expression of political views, this is a personal affair as it depends on one’s interests, lifestyle, faculty, or the discipline that one is exposed to, as well as social conditions and trends. There is a need to pay special attention to the unique circumstances of the southern border provinces (Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat) when discussing the digital expression of political behavior. These provinces have a culturally diverse society made up of Muslims, Buddhists, and others, which may influence how political behavior is expressed and perceived. The region has received special attention from the government because of its unrest, referred to as the “Southern Conflict,” for several years. The conflict is a sensitive and complex problem with regard to its social, psychological, economic, political, and governance aspects, especially given the mutual misunderstanding and suspicion between the people and government officials. This explains the greater interest in politics among Generation Z in the southern border provinces compared to other areas (Jati 2020; Nipapan 2020; Nawapon 2022).

Education level is believed to have a strong influence on digital political behavior (Campbell 2013). Political participation is a common concern among Generation Z, who are currently students at university and high school, in terms of expressing their opinions through various online media platforms. X/Twitter is a popular social media platform among young people around the world, as in Thailand. Through the use of hashtags (#) on X/Twitter, Generation Z often engage with social and political movements such as “#เยาวชนปลดแอก” (#Yeawachon plodxaek, Free Youth), one of the student movements that played a significant role in the 2020 protests. Free Youth is believed to have the largest following among all the movements (Wichuda and Theetat 2021), with over 1.9 million followers on its Facebook page as of November 2023 and nearly 400,000 followers on Twitter. Such groups mostly use social media for political awareness and information. They also believe that political efficacy plays a significant role in influencing political activities (Ahmad et al. 2019), as has been explained by Kanokrat (2022) in the context of Thailand. However, the flip side of the coin is that certain people may attempt to manipulate Generation Z by providing false information and use such groups as tools to influence social movements and political behaviors. Social media is a double-edged sword: in addition to being useful it can cause harm.

Occupation: Members of Generation Z in each occupation show different digital political behaviors depending on their knowledge, attitude, values, experience, and social refinement. For example, civil servants and government employees may engage in more formal and policy-focused online discussions, while private company employees might participate in debates related to business and economic policies. High school and university students, on the other hand, are often more vocal about social justice issues and educational reforms. In this study, occupation is found to be related to income: Generation Z individuals of working age (civil servants, government employees, state enterprise employees, and private company employees) are observed to have higher incomes than those of school age (high school students, university students, and new graduates/unemployed). Higher income can provide access to better technology and more time for online engagement, which influences digital political behavior. In addition, parenting styles in Thai society tend to be more authoritative and permissive than authoritarian as in the past (Haerpfer et al. 2022). This shift in parenting style has led to positive social outcomes since parents are still somewhat in control of their school-age children. Most of these children are still being raised and financially supported by their parents, which forces them to have a narrower worldview and viewpoint than people in the working-age group of Generation Z (Gidengil et al. 2016; Rungrat 2020). Although digital political behavior varies from person to person, those with a broad worldview who continuously follow up on information and are exposed to news are more adept at understanding and interpreting political messages, rhetoric, and discourse, including the use of language in communication.

Domicile: The Generation Z group selected to participate in this research reside in the southern part of Thailand, a region with strong political participation. All Thai governments pay attention to the southern border provinces (Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat) since they are far from the capital and adjacent to neighboring countries such as Malaysia, which have similar cultures—social, religious, or traditional. The area is unique in that it is a “multicultural society” (Adizin 2017; Thailand, Office of Strategy Management, South Border 2023). The southern border provinces are also regarded as a conflict area, with the government having established the Southern Border Provinces Administration Center (SBPAC) to play an important role in formulating policies for it. As defined in Section 9 of the Southern Border Provinces Administration Act, B.E. 2553, the SBPAC has the following roles and missions: (1) implementing strategies for the development of the southern border provinces; (2) protecting rights and freedoms, providing justice, providing remedial assistance to those who have been impacted by the actions of government officials, promoting the participation of people from all sectors in tackling problems in the southern border provinces; and (3) serving as a bridge between the development strategy of the southern border provinces and the strategy of the Internal Security Operations Command.

Conclusion

Online media, with its benefits and disadvantages, plays a role in determining values and behaviors, especially the political behavior of Generation Z—children, youths, adults, and people of working age. Therefore, it is important to study the digital political behavior of Generation Z (see Fig. 1). This generation is vital in determining Thailand’s future: Generation Z individuals will be the ones driving the country forward in the next twenty years. Thus, it is necessary for the government to formulate policies promoting constructive digital political behavior among this generation, to act as guidelines for social harmony. It is a crucial duty of government agencies to guide and direct people’s values, patterns, and behaviors. This is part of the development and empowerment of human resources as stipulated in the “20-year national development strategy [2018–37]” (Thailand, Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council 2020).

Accepted: January 9, 2024

Acknowledgments

This research received support from the Basic Research Grant of Prince of Songkla University, Thailand (contract no. CAM6402016S).

References

Adizin Nirae อาดิซีน หนิเร่. 2017. Thassana khong klumkhon runmai nai phuenthi samchangwat chaidaenthai tee mee to panha kwammaisangop tee kerdkhuen nai phuenthi ทัศนคติของกลุ่มคนรุ่นใหม่ในพื้นที่สามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้ที่มีต่อปัญหาความไม่ สงบที่เกิดขึ้นในพื้นที่ [The attitude of the new generation in the three southern border provinces toward the unrest in the area]. Research report. Bangkok: Thammasat University.↩ ↩

Ahmad, Taufiq; Alvi, Aima; and Ittefaq, Muhammad. 2019. The Use of Social Media on Political Participation among University Students: An Analysis of Survey Results from Rural Pakistan. Sage Open 9(3): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019864484.↩ ↩

Attasit Pankaew; Stithorn Thananithichot; and Wichuda Satidporn. 2022. Determinants of Political Participation in Thailand: An Analysis of Survey Data (2002–2014). Asian Politics & Policy 14(1): 92–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12625.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Bronstein, Jenny and Aharony, Noa. 2015. Personal and Political Elements of the Use of Social Networking Sites. In Proceedings of ISIC: the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, September 2–5, 2014. https://www.informationr.net/ir/20-1/isic2/isic23.html#.YFjTp68zbIU, accessed March 21, 2023.↩ ↩

Campbell, David. 2013. Social Networks and Political Participation. Annual Review of Political Science 16: 33–48. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-033011-201728.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Carmines, Edward G. and Huckfeldt, Robert. 2003. Political Behavior: An Overview. In A New Handbook of Political Science, edited by Robert E. Goodin and Hans-Dieter Klingemann, pp. 223–254. New York: Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198294719.003.0008.↩

Chareon Yuthong-Sanguthai จรูญ หยูทอง. 2018. Phaktai: kanmuang lae phakrat ภาคใต้: การเมืองและภาครัฐ [Southern region: Politics and public sector]. Songkhla: Institute for Southern Thai Studies, Thaksin University.↩

Chenin Chen เชนินทร์ เชน. 2020. Phuettikam khong khonrun Y to khwamsanook nai sathanthithamngan khong borisat kamchat nai prathet Thai พฤติกรรมของคนรุ่น Y ต่อความสนุกในสถานที่ทำงานของบริษัทข้ามชาติในประเทศไทย [Behavior of generation Y toward workplace fun in multinational companies in Thailand]. Romphruek Journal 38(1): 83–99.↩

Cho, Alexander; Byrne, Jasmina; and Pelter, Zoë. 2020. Digital Civic Engagement by Young People. New York: UNICEF.↩

Coleman, Stephen and Norris, Donald. 2005. A New Agenda for e-Democracy. New York: Social Science Research Network Press.↩ ↩ ↩

Cottam, Martha L.; Dietz-Uhler, Beth; Mastors, Elena; and Preston, Thomas. 2010. Introduction to Political Psychology. Second Edition. New York: Psychology Press.↩

Dimitrova, Daniela; Shehata, Adam; Strömbäck, Jesper; and Nord, Lars. 2014. The Effects of Digital Media on Political Knowledge and Participation in Election Campaigns: Evidence from Panel Data. Communication Research 41(1): 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211426004.↩ ↩

Dolot, Anna. 2018. The Characteristics of Generation Z. e-mentor 74(2): 44–50. https://doi.org/10.15219/em74.1351.↩

Evans, Olaniyi. 2019. Digital Politics: Internet and Democracy in Africa. Journal of Economic Studies 46(1): 169–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-08-2017-0234.↩

Farrell, Wendy Colleen and Tipnuch Phungsoonthorn. 2020. Generation Z in Thailand. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 20(1): 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595820904116.↩ ↩

Gerodimos, Roman. 2005. Democracy and the Internet: Access, Engagement and Deliberation. Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics 3(6): 26–31.↩

Gibson, Rachel; Lusoli, Wainer; and Ward, Stephen. 2005. Online Participation in the UK: Testing a “Contextualised” Model of Internet Effects. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 7(4): 561–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2005.00209.x.↩

Gidengil, Elisabeth; Wass, Hanna; and Valaste, Maria. 2016. Political Socialization and Voting: The Parent-Child Link in Turnout. Political Research Quarterly 69(2): 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912916640900.↩ ↩

Gil de Zúñiga, Homero and Chen Hsuan-Ting. 2019. Digital Media and Politics: Effects of the Great Information and Communication Divides. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 63(3): 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2019.1662019.↩

Grönlund, Åke. 2003. Emerging Electronic Infrastructures: Exploring Democratic Components. Social Science Computer Review 21(1): 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439302238971.↩

Haerpfer, Christian; Inglehart, Ronald; Moreno, Alejandro; et al., eds. 2022. World Values Survey: Round Seven: Country-Pooled Datafile Version 5.0. Madrid and Vienna: JD Systems Institute and WVSA Secretariat. https://doi.org/10.14281/18241.20.↩

Hatemi, Peter K.; Medland, Sarah E.; and Eaves, Lindon J. 2009. Do Genes Contribute to the “Gender Gap”? Journal of Politics 71(1): 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381608090178.↩ ↩ ↩

Howe, Neil; Strauss, William; and Nadler, Reena. 2008. Millennials & K-12 Schools: Educational Strategies for a New Generation. Richmond: LifeCourse Associates Press.↩

Huddy, Leonie; Sears, David; Levy, Jack; and Jerit, Jennifer. 2023. The Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.↩

Jati, Wasisto Raharjo. 2020. Review of Scandal and Democracy: Media Politics in Indonesia by Mary E. McCoy. Southeast Asian Studies 9(2): 281–284. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.9.2_281.↩ ↩

Jirayut Monjagapate and Nakorn Rungkittanasan. 2020. The Study of Acceptance Thai LGBTQs in Bangkok: Analysis of Attitudes from Gen-Z People. International Journal of Information Privacy, Security and Integrity 4(2): 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIPSI.2019.10028198.↩

Kanokrat Lertchoosakul. 2022. The Rise and Dynamics of the 2020 Youth Movement in Thailand. Brussels: Heinrich-Böll-Stifung Democracy Publishing.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Kasit Piromya. 2023. Thailand Rejected the Old Ways: It’s up to the New Generation to Move Democracy Forward. South China Morning Post (blog). June 24. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3225159/thailand-rejected-old-ways-its-new-generation-move-democracy-forward?, accessed September 29, 2023.↩

Khemthong Tonsakulrungruang. 2020. Review of Fighting for Virtue: Justice and Politics in Thailand by Duncan McCargo. Southeast Asian Studies 9(3): 485–488. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.9.3_485.↩ ↩ ↩

Klinger, Ulrike. 2023. Algorithms, Power and Digital Politics. In Handbook of Digital Politics, edited by Stephen Coleman and Lone Sorensen, pp. 210–258. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.↩

Kritdikorn Wongswangpanich. 2023. Review of Dynastic Democracy: Political Families in Thailand by Yoshinori Nishizaki. Southeast Asian Studies 12(2): 373–378. https://doi.org/10.20495/seas.12.2_373.↩ ↩

Kununya Atthmongkolchai. 2022. Generation Z’s Expressions of Dissatisfaction in the Thailand Context. Research report, University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce.↩

Lidén, Gustav. 2015. The Policy Making of Digital Politics: Examining the Local Level in Sweden. Paper presented at the Second International Conference on Public Policy, Milan, July 1–4. https://www.ippapublicpolicy.org/file/paper/1433853893.pdf, accessed March 21, 2023.↩ ↩ ↩

McCann Worldgroup. 2022. The Truth about Gen Z. McCann Worldgroup. https://truthaboutgenz.mccannworldgroup.com/p/1, accessed September 30, 2022.↩

Miller, Carl. 2016. The Rise of Digital Politics. Research report, Demos.↩

Mols, Frank and ’t Hart, Paul. 2018. Political Psychology. In Theory and Methods in Political Science, edited by Vivien Lowndes, David Marsh, and Gerry Stoker, pp. 142–157. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.↩ ↩ ↩

Nawapon Kaewsuwan นวพล แก้วสุวรรณ. 2022. Phuettikam kansuesan sarasonhtet thang kanmuang khong yaowachon nai samchangwat chaidaenphaktai พฤติกรรมการสื่อสารสารสนเทศทางการเมืองของเยาวชนในสามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้ [Political information communication behavior of youths in three southern border provinces]. Research report, Prince of Songkla University.↩ ↩

Nipapan Jensantikul นิภาพรรณ เจนสันติกุล. 2020. Samchangwat chaidaenphaktai khwam pen sathaban lae kankratham pai tai thissadee khrongsang nathi niyom สามจังหวัดชายแดนภาคใต้ ความเป็นสถาบันและการกระทำภายใต้ทฤษฎีโครงสร้างหน้าที่นิยม [Three southern border provinces institutionalization and action under structural functionalism theory]. Suthiparithat Journal 27(84): 77–90.↩

Nuchchamon Pramepluem ณัชชามน เปรมปลื้ม; Manop Chunin มานพ ชูนิล; and Pinkanok Wongpinpech ปิ่นกนก วงศ์ปิ่นเพ็ชร. 2019. Patjai choenghet lae phon khong phuettikam kanpen samachik thi di khong ongkan khongkhru generation y sangkat sumnaknganket pheuntikansuksa mattayomsuksa ket kao ปัจจัยเชิงเหตุปละผลของพฤติกรรมการเป็นสมาชิกที่ดีขององค์การของครูเจเนอเรชั่นวายสังกัดสำนักงานเขตพื้นที่การศึกษามัธยมศึกษาเขต 9 [Antecedent and consequence factors of Generation Y teachers’ organizational citizenship behavior under the Secondary Educational Service Area Office 9]. Journal of Public Administration and Politics 8(3): 24–44.↩

Parin Kritsunthon ปริญญ์ กฤษสุนทร and Jirawate Rugchat จิรเวทย์ รักชาติ. 2020. Kanwikhro ong prakop khong sue VDO game nai pi phoso 2557–2562 การวิเคราะห์องค์ประกอบของสื่อวีดีโอเกมในช่วงปี พ.ศ. 2557–2562 [An analysis of video game media elements during 2014–2019]. Journal of Communication and Integrated Media 8(2): 36–66.↩

Phattarapan Nithiwaratsakul ภัทรพันธุ์ นิธิวรัตน์สกุล and Karisa Sutthadaanantaphokin ฆฬิสา สุธดาอนันตโภคิน. 2023. Awachanaphasa: sanyalak kankhueanwai thang kanmuang khong yaowachon Thai อวัจนภาษา: สัญลักษณ์การเคลื่อนไหวทางการเมืองของเยาวชนไทย [Nonverbal language: Symbol of the political movement of Thai youths]. Journal of Roi Kaensarn Academi 8(3): 528–539.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Phrakhrusamusuwan Viriyo พระครูสมุห์สุวรรณ วิริโย. 2023. Kanmuang khong khonrunmai nai sangkhom Thai การเมืองของคนรุ่นใหม่ในสังคมไทย [Politics of the new generation in Thai society]. Academic Journal of Political Science and Public Administration 5(1): 13–23.↩ ↩ ↩

PhraNatthawut Phanthali พระณัฐวุฒิ พันทะลี; Sukhapal Anonjarn สุขพัฒน์ อนนท์จารย์; Artit Saengchawek อาทิตย์ แสงเฉวก; and Weeranuch Promjak วีรนุช พรมจักร์. 2022. Kankleunwai thang kanmuang Thai khong khonrunmai nai sangkhom Thai การเคลื่อนไหวทางการเมืองของกลุ่มคนรุ่นใหม่ในสังคมไทย [Political movements of the new generation in Thai society]. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Mahamakut Buddhist University Isan Campus 3(3): 56–70.↩ ↩ ↩

Pongsavake Anekjumnongporn พงศ์เสวก เอนกจำนงค์พร. 2019. Phuettikam kanrapru kanthongthiew khong prachakhon run Y: korani suksa naksuksa radap parinyatri พฤติกรรมการรับสื่อกับการรับรู้การท่องเที่ยวของประชากรรุ่นวาย: กรณีศึกษานักศึกษาระดับปริญญาตรี [Media exposure behavior and Generation Y’s perception of tourism: Case study of undergraduate students]. Journal of Liberal Arts, Prince of Songkla University 11(2): 371–389.↩

Purawich Watanasukh ปุรวิชญ์ วัฒนสุข. 2023. Kanmuang lung leuktang 66 kanplienplaeng kap phalang social การเมืองหลังเลือกตั้ง 66 การเปลี่ยนแปลงกับพลังสื่อโซเชียล [Politics after the ’66 election, changes in politics and the influence of social media]. Thammasat University Press (blog). June 7. https://tu.ac.th/thammasat-070666-politics-after-the-election#content-0, accessed September 25, 2023.↩ ↩ ↩

Rungrat Sukadaecha รุ่งรัตน์ สุขะเดชะ. 2020. Kanobrom liengdu dek khong khropkhrua Thai: kanthopthuan wannakam baep buranakan yang pen rabop การอบรมเลี้ยงดูเด็กของครอบครัวไทย: การทบทวนวรรณกรรมแบบบูรณาการอย่างเป็นระบบ [Child-rearing in Thai families: A systematic integrated literature review]. Journal of Nursing Science & Health 43(1): 1–9.↩

Ruqayya Aminu Gar; Mohammed Nuru Umar; and Murtala Muhammad. 2022. Understanding the Concept of Political Behaviour. SocArXiv 44(2): 355–380. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/txqzj.↩ ↩ ↩

Saksin Udomwittayapaisarn ศักดิ์สิน อุดมวิทยไพศาล; Yupaporn Yupas ยุภาพร ยุภาศ; and Sanya Kenaphoom สัญญา เคณาภูมิ. 2019. Krop naewkit choeng phuttikam thang kanmuang khong prachachon กรอบแนวคิดเชิงทฤษฎีพฤติกรรมทางการเมืองของประชาชน [Theoretical conceptual framework of people’s political behaviors]. Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, UBRU 10(1): 293–306.↩ ↩

Sen, Ronojoy and Murali, Vani Swarupa. 2018. Digital Politics: Emerging Trends in South and Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of South Asian Studies.↩ ↩ ↩

Somit, Albert and Peterson, Steven A., eds. 2011. Biology and Politics: The Cutting Edge. Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing.↩

Somkiat Tangkitvanich. 2022. Time to End Thailand’s Generation War. Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI) (blog). December 9. https://tdri.or.th/en/2022/12/time-to-end-thailands-generation-war/, accessed September 29, 2023.↩

Sudarat Promsrimai สุดารัตน์ พรมสีใหม่. 2023. Mong Nayobai reuang phet nai khong sutthay kon leuaktang มองนโยบายเรื่องเพศในโค้งสุดท้ายก่อนเลือกตั้ง [Looking at the Policies Regarding Gender in the Final Stretch before the Election]. The 101.world (blog). May 13. https://www.the101.world/gender-policies-in-election/, accessed September 25, 2023.↩

Suthida Pattanasrivichian สุธิดา พัฒนศรีวิเชียร. 2019. Phalang khong suesangkhom kap kankhapkluean khabuenkan khluenwai thang sangkhom mai พลังของสื่อสังคมกับการขับเคลื่อนขบวนการเคลื่อนไหวทางสังคมใหม่ [The power of social media in mobilizing the new social movement]. Academic Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Burapha University 27(53): 132–155.↩

Taufik Alamin; Darsono Wisadirana; Sanggar Kanto; Hilmy Mochtar; Sholih Mu’adi; and Mardiyono Mardiyono. 2020. Political Change Patterns of the Mataraman Society in Kediri. Journal of Development Research 4(2): 106–114. https://doi.org/10.28926/jdr.v4i2.121.↩ ↩

Thailand, National Assembly of the Kingdom of Thailand. 2017. Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand (B.E. 2560 [2017]). Constitution Drafting Commission. https://cdc.parliament.go.th/draftconstitution2/more_news.php?cid=128, accessed January 5, 2023.

Thailand, National Statistical Office. 2023. Report of Population from Registration Classified by Age Group, Gender and Province 2023. Ministry of Digital Economy and Society, Thailand.↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

Thailand, Office of Strategy Management, South Border. 2023. Administration of Southern Border Province Policy. Office of the Prime Minister, Thailand. https://www.osmsouth-border.go.th/frontpage, accessed January 5, 2023.↩

Thailand, Office of the Election Commission of Thailand. 2023. General MP Election Results, May 14, 2023. https://ectreport66.ect.go.th/overview, accessed November 16, 2023.↩

Thailand, Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. 2020. Report of Human Development to Support the Country’s Movement. Office of the Prime Minister, Thailand. https://www.nesdc.go.th/ewt_w3c/ewt_news.php?nid=9953&filename=, accessed January 5, 2023.↩ ↩

Thailand, Secretariat of the Cabinet. 2015. Gender Equality Act (B.E. 2558 [2015]). https://law.m-society.go.th/law2016/uploads/lawfile/594cc091ca739.pdf, accessed September 26, 2024.↩

Turner, Anthony. 2018. Generation Z: Technology and Social Interest. Journal of Individual Psychology 71(2): 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1353/jip.2015.0021.↩

Udupa, Sahana; Venkatraman, Shriram; and Khan, Aasim. 2020. “Millennial India”: Global Digital Politics in Context. Television & New Media 21(4): 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419870516.↩

United Nations. 2023. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals, accessed January 5, 2023.↩

Veera Lertsomporn วีระ เลิศสมพร. 2016. Prachathippatai electronic: serm sang rue chut rang ประชาธิปไตยอิเล็กทรอนิกส์: เสริมสร้างหรือฉุดรั้ง [Electronic democracy: Strengthen or hold back?]. Political Sciences and Public Administration Journal 7(1): 138–160.↩

Wanwilai Phochai วรรณวิไล โพธิ์ชัย. 2019. Khunkha trasinkha lae patjai dan kansuesan kantalat thi song phon to kantatsinjai sue phalitapan serm ahan puea sukkaphap khong kum gen y nai krungthepmahanakhon คุณค่าตราสินค้าและปัจจัยด้านการสื่อสารการตลาดที่ส่งผลต่อการตัดสินใจซื้อผลิตภัณฑ์เสริมอาหารเพื่อสุขภาพของกลุ่ม Gen Y ในกรุงเทพมหานคร [Brand equity and marketing communications influencing purchase decisions toward supplementary food of generation Y in Bangkok]. Journal of Development Administration Research 9(3): 87–95.↩

Wichuda Satitporn วิชุดา สาธิตพร and Theetat Chandrapichit ธีทัต จันทราพิชิต. 2021. Klum yaowachon plot aek กลุ่มเยาวชนปลดแอก [Free Youth]. King Prajadhipok’s Institute (blog). June 17. http://wiki.kpi.ac.th/index.php?title=Free_youth, accessed September 25, 2023.↩