Contents>> Vol. 8, No. 2

Dear Thai Sisters: Propaganda, Fashion, and the Corporeal Nation under Phibunsongkhram

Kanjana Hubik Thepboriruk*

* กัญจนา เทพบริรักษ์ Department of World Languages and Culture, Northern Illinois University, 335 Watson Hall, DeKalb, IL 60115, USA; Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Northern Illinois University, 520 College View Court, DeKalb, IL 60115, USA

e-mail: kanjana[at]niu.edu

DOI: 10.20495/seas.8.2_233

Embodying modernity and nationality was a self-improvement task for fin de siècle Siamese monarchs. In post-1932 Siam, kingly bodies no longer wielded the semantic and social potency necessary to inhabit the whole of a nation. Siam required a corporeal reassignment to signify a new era. This study examines previously neglected propaganda materials the Phibunsongkhram regime produced in 1941 to recruit women for nation building, specifically, the texts supplementing Cultural Mandate 10 addressed to the “Thai Sisters.” I argue that with the Thai Sisters texts, the regime relocated modernization and nation building from male royal bodies onto the bodies of women. Moreover, these texts specified gendered roles in nation building and inserted nationalism into the private lives of women by framing nationbuilding tasks as analogous to self-improvement and the biological and emotional experiences of a mother. Vestimentary nation building prescribed by Mandate 10 turned popular magazines into patriotic battlegrounds where all Thai Sisters were gatekeepers and enforcement came in the form of photo spreads, advertisements, and beauty pageants. By weaving nation building into fashion and the private lives of women, the Phibunsongkhram regime made the (self-)policing of women’s bodies—formerly restricted to elite women—not only essential but also fashionable and patriotic for all Thai Sisters.

Keywords: Thailand, nation building, women, fashion

I Introduction

On October 4, 1941 various Thai government ministers gathered in the capital of Nong Khai Province to celebrate the opening of a district office of the Publicity Department. Attendees at the celebration received a small commemorative volume titled “Collection of Mandates, Codes, and Guidelines for National Culture.”1) There is one copy of this commemorative volume in the Rare Books Archives at the National Library of Thailand, its pages crumbling and held together by twine. The booklet is a collection of supplemental publications to the 12 Cultural Mandates.

Nestled in the 188 pages are seven documents addressed to “Thai Sisters” (phi nong satri thai) published by various government agencies of the Phibunsongkhram regime in 1941. There are no texts in this volume that directly address Thai men. It is noteworthy that the Phibunsongkhram regime would specifically target women during this transformative period in Thai history and then later deem such publications valuable enough to be reprinted in a commemorative volume. Not only does this remarkable subset of texts offer a glimpse into the regime’s notion of the ideal modern woman, it is also one of the earliest examples of the government’s attempt to recruit women for the task of nation building. Why were women targeted for these texts, and to what end? What do these texts reveal about the nationalization and modernization of Siamese women during that time?

This particular period of Thai history has very few analyses focusing on women, especially in English, despite Phibunsongkhram enjoying a recent resurgence of interest among scholars of Thai studies.2) The discovery and analysis of these neglected archival materials show that the regime saw it necessary to produce materials specifically for women; thus, women’s role and participation in nation building during this transformative period warrants further study. The language in such propaganda, moreover, is always deliberate, and a textual analysis of these Thai Sisters documents can reveal the nationalistic ideology toward women. The current study explores how the Phibunsongkhram regime recruited women for nation building through propaganda and, in the process, conscripted women’s bodies as corporeal proxies for the nation. It is my hope that this study will help to advance discussions on the condition of Siamese women during this era as well as show the importance of these texts in Thai national history.

I use translations from Thak et al. (1978) for the Cultural Mandates. All other Thai-English translations are my own, including all translations of primary sources referenced herein. English transliterations of Thai, including names of individuals, follow the standards prescribed by the Royal Institute of Thailand (1999), unless a different transliteration is already well established and widely accepted. Transliterations of names always follow those used by the individuals when applicable. Thai words are transliterated, italicized, and given in parentheses after the English translation in the text.

II Modern Nation

Making of a Nation

The Kingdom of Siam went through an intense period of transformation starting in the mid-nineteenth century. Higher levels of literacy in the growing middle class combined with new forms of mass media such as the cinema and wireless radio fueled considerable social, economic, and political changes in Siam that continued well into the interwar period (Barmé 2002).3) The dismantling of traditional power structures after the Great War, including the disintegration of the monarchy system, was buoyed by a worldwide undercurrent of social, economic, and political anxiety and instability. Several conservative military regimes grew to fill the power vacuum left by deposed monarchs.4) Like elsewhere in the world, the interwar years in Siam were especially tumultuous, in this case punctuated by the 1932 coup d’état that ended absolute monarchy and resulted in the abdication of King Prajadhipok (Rama VII) in 1935.5)

In the century leading up to the 1932 coup, nation building and modernization was a central theme in the public lives of Siamese Kings. The Kings of House Chakri, established in 1782 with Bangkok as its new seat of power, traditionally borrowed the aesthetics and material culture from nearby empires in China and India to sanctify and legitimize their claims on the Siamese throne (Peleggi 2002, 12–13). But by the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV), Europe had become the new locus of “progress” and “civilization” and Siamese royal culture began its retreat from the Indo- and Sino-spheres. Linguistically, the Pali-Sanskrit term arayatham was replaced by one modeled after the English word for “civilization,” siwilai. Rama IV, his son King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), and his grandson King Vajiravudh (Rama VI) gradually recalibrated the Siamese royal image to align more closely with the West and looked to their European peers as the source for siwilai (ibid).

The pursuit of siwilai was visually accompanied by a gradual shift toward Western modes of dress among Siamese elites. The modernization of Siamese royal bodies through the conspicuous consumption of and participation in Western culture was the visual representation of Siam as a modern nation (Peleggi 2002). Siwilai, as indexed by the monarchs’ increasingly Westernized public image, and the very act of being photographed looking so, was a kingly task. Through this public performance of siwilai, Siamese Kings positioned themselves as benevolent arbiters of the West, patrolling the cultural frontline against any pernicious foreign ideas and proffering a uniquely Siamese vision of modernity for aspiring elites and other subjects to emulate.

Beyond looking civilized and aligning Siamese aesthetics with Western ideals, the quest for siwilai also required a bifurcation of traditional Siamese genders into male/masculine and female/feminine. Western records of Siamese modes of dress from as early as the seventeenth century show that both men and women had the same style of short hair and wore the same phanung or chong kraben to cover their lower bodies.6) Unaccustomed to local ways of gender demarcation, Westerners were left unsettled and disoriented by their inability to visually distinguish men from women (ibid). As Peter Jackson (2003) points out, the Western-inspired system of genders not only created new social distinctions between men and women in Siamese society but also left no room for traditional genders that did not fit into the male/female binary.

Elsewhere in mainland Southeast Asia, traditional ways of presenting and marking gender were cleaving into binaries under the weight of colonial powers and fashion while previously unisex aspects of local cultures were becoming gendered. Europeans indexed the perceived lack of gender distinction in Southeast Asian modes of dress with a lack of civility and culture and began assigning gender to traditionally non-gendered or unisex fashion. The Cambodian sampot and the short jacket that both men and women wore, for example, became feminine and masculine, respectively (Edwards 2001). Like in Siam, unisex hairstyles in French Cambodia (shorn short) and British Burma (long and coiled atop the head) became gendered (ibid; Ikeya 2011).

Siamese Kings of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were keenly aware of Western prejudices against unisex sartorial practices of the Siamese people and their neighbors. King Mongkut (Rama IV) ordered all to wear upper garments when in royal audience. His son Rama V, who was famously educated by an English governess, issued the first royal decree on clothing for the general public in 1899 that limited what should be worn in public and at court. The decree marks the beginning of the relationship between morality and clothing in Siam (Jackson 2003). Rama VI, who was educated entirely in England, further pushed for gendered fashion and discouraged women at court from traditional Siamese styles, thus rendering formerly unisex hairstyles and chong kraben masculine. By the time Rama VII came into power, the King and the men and women in his court were entirely covered up, sported contemporary Western hairstyles, and were appropriately masculine and feminine by Western standards.

The canonization of the Siamese King’s body (and, by extension, any other bodies in his household) to represent the nation and the metonymic use of Siam to mean the King were not novel. Ernst Kantorowicz’s detailed work The King’s Two Bodies (1997) shows that the twin representation of kingly bodies as the realm and the individual can be traced back to the medieval period in Europe, the linguistic manifestations of which can be found in the use of the “royal we.” The bodies of royal women, likewise, served as political proxies and were exchanged in diplomatic transactions through strategic marriages. By the eighteenth century, the emblematic binding between the King’s body and the state was so strong that French revolutionaries were able to use corporeal metaphors to attack the man and the institution. The corporeality of the French state in Louis XVI’s body culminated in making his beheading a compulsory part of the destruction of the ancien régime (De Baecque 1993). In post-1932 Siam, kingly bodies no longer wielded the semantic and social potency necessary to embody the whole of a nation. Siam required a corporeal reassignment to signify a new era.

Phibunsongkhram’s Cultural Mandates

Army Major General Plaek Phibunsongkhram maneuvered his way into power in 1938. Phibunsongkhram was a member of the People’s Party (Khana Ratsadon), a group comprising Western-educated civil servants, military officers, and minor royals. The group orchestrated the 1932 coup d’état that ended absolute monarchy in Siam. Shortly after his ascent to premiership, Phibunsongkhram followed his European contemporaries and rebranded himself as “The Leader” (phu nam). He also attempted to ritually fill the symbolic void left by Rama VII’s relatively recent abdication and the child-king Rama VIII’s geographic distance in Switzerland (Gray 1991, 50). Visually, the regime ordered the public to replace pictures of the deposed Rama VII with those of Phibunsongkhram (Thamsook 1978, 237). The army general, however, lacked the cultural legitimacy of prelapsarian Siamese Kings, and the Phibunsongkhram government needed to canonize a new body as the nation.

The regime’s nation-building campaign aimed to transform the Kingdom of Siam into the nation of Thailand and Siamese subjects into Thai citizens by thrusting Siam into modernity and, paradoxically, by building a democratic and constitutional nation with their unelected government. To that end, Phibunsongkhram and his chief ideologue, Luang Wichit Watthakan, created the Cultural Mandates (ratthaniyom) to be the centerpiece of their social policies.7) The regime issued a total of 12 Cultural Mandates between June 1939 and January 1942. The mandates transformed Siam into Thailand and all people living within the borders into Thai/Tai people (Mandates 1 and 3); dictated new and modern ways of life (Mandates 7, 11, and 12); designated a mode of dress (Mandate 10); described duties of nation building (Mandates 2, 5, 7, and 9); and sanctified the nation and, in a much lesser manner, the monarchy as unifying forces for the Thai people (Mandates 4, 6, and 8).

Mandate 10, issued on January 15, 1941, is particularly interesting because it imposed, for the first time and at a national level, a new and modern aesthetic of self-presentation for everyone regardless of social class. The mandate did not apply uniformly to men and women, as evidenced by the body of texts aimed at the Thai Sisters.8) The mandate states that “Thais should not appear in public, populous places, or in municipal areas without proper clothing . . .” (Thak et al. 1978, 253, emphasis added). The Thai term in the original text is riap roi, which has many meanings. When used to describe inanimate objects, it means “tidy,” “orderly,” or “in good order.” But when describing a person, the term means “well-mannered” or “polite.” A task that is riap roi is one that is “ready” or “all set.” Taken together, to dress riap roi is to present oneself as someone who is tidy, well-mannered, and ready for nation building.

At the height of Siamese cultural and political influence in mainland Southeast Asia, vestimentary regulations through enforcements of sumptuary laws affected only those whose ranks and positions required identifiers to visually partition them from the rest of society (Conway 2002). Members of the growing middle class emulated the sartorial practices of traditional elites to visually index their social aspirations. Commoners outside of Bangkok’s cultural spheres were left mostly unaffected by such regulations and only needed passive knowledge of those visual markers pertaining to official rank. With the issuance of Mandate 10, the regime not only erased—albeit just in theory—the sartorial class separations previously outlined by sumptuary laws but also created a uniformed way to present Thai identity at a national level. Without a monarch to embody modernity and the nation, the burden fell on everyone.

As a supplement to the Cultural Mandates, the regime produced and disseminated various texts to clarify and explicate the barrage of modern demands made on the public. These supplemental texts took advantage of all available modes of communication and came in many forms. The texts were not intended solely for the general population and were (re-)printed for civil servants in internal bulletins such as Khao Khotsanakan (Publicity News), a magazine for employees of the Publicity Department. The Phibunsongkhram government had full censorship control of information, so popular media, too, had to participate in creating the ideological echo chamber that was the cultural backdrop to their totalitarian nation building. Media outlets that refused to participate or had values deemed to be “against national interests” were shut down (Thamsook 1978, 244).

The following sections will discuss examples from supplemental texts that the Phibunsongkhram regime produced for Mandate 10 and their influence in contemporary print media. The supplemental texts targeted women and were addressed to the “Thai Sisters” (phi nong satri thai) and “Esteemed Thai Sisters/Ladies Everywhere” (phi nong satri thai thi nap thue/than suphap satri phu mi kiat thang lai). Analyses are pulled from popular print media, periodicals, and internal government magazines. I argue that in the absence of a kingly body, the regime produced the Thai Sisters texts in order to: (1) transfer the physical burden of modernity and nation building onto the bodies of women, (2) specify gendered roles for nation building by extending nationalism into the private lives of women, and (3) thereby create an environment for women to self-police under the guise of patriotism and fashion. These supplemental texts offer an insightful cross-section of the regime’s ideology toward modernity, womanhood, and women’s gendered role in nation building.

Dear Thai Sisters

Between March and September 1941, the regime disseminated eight supplemental texts in rapid succession to complement Mandate 10. The texts (listed below) targeted women and were addressed to “Thai Sisters” and “Esteemed Ladies Everywhere.” Together, they provide an enormous amount of detail on how women were to put Mandate 10 into practice.

1. The Prime Minister’s Plea (For Our Thai Sisters), March 14, 1941

2. The Prime Minister’s Plea for Our Thai Sisters, Titled “Wearing Hats,” June 14, 1941

3. Ways to Wear Hats for Thai Ladies, speech delivered by Mr. Ensee Intharayothin over the wireless, June 19, 1941

4. Explanation, Titled “Finding Hats,” June 20, 1941

5. Ways to Wear Hats for Thai Ladies, Part 2, speech delivered by Mr. Ensee Intharayothin over the wireless, June 29, 1941

6. Explanation, Titled “Wearing Hats into Suan Kulap Palace,” July 1, 1941

7. Guidelines on Ways of Dress for Ladies

a. Part 1, August 27, 1941

b. Part 2, speech delivered by Amon Osathanon over the wireless, September 2, 1941

The discourse of the Thai Sisters texts was always deferential in nature, and the tone ranged from official (“Finding Hats” and “Suan Kulap”) to informal (First Plea, Second Plea). Though framed as a series of personal dialogues with women, the content, in reality, made concrete commands on their bodies and minds.

Signatories of the texts included both individuals and government units. Based on the relatively uniform style, it is unlikely that each text was personally crafted by the signatories. The texts were most likely written and approved by a group in the Publicity Department. Signatories such as Phibunsongkhram and Ensee Intharayothin, the head of the Office of Consumer Welfare, even when presented as individuals, simply anthropomorphized the regime. The sole female signatory was Amon Osathanon. Amon sat on the council that outlined the Guidelines for Women’s Dress and was married to Wilat Osathanon, a member of the 1932 Khana Ratsadon who served as the regime’s deputy minister of transport. Amon’s address was the last of the Thai Sisters texts. Besides having the friendliest discourse of all the texts, utilizing a conversational approach, humor, and the pronoun “we,” her radio address was otherwise unremarkable.

III Corporeal Nation

Patriotic Propriety

The first message from Phibunsongkhram to the “Thai Sisters” was on March 14, 1941 and titled “The Prime Minister’s Plea (for Our Thai Sisters).”9) In the plea, Phibunsongkhram asked the Thai Sisters to celebrate the victorious return of “lost territories” from the French by doing three things: (1) grow out their hair, following ancient customs or in modern styles; (2) cease wearing cloth styled into pantaloons (chong kraben) and, instead, wear sarong-style wrap skirts (pha thung) in the traditional ways or following modern styles; and (3) cease wrapping a single piece of cloth on their torso or baring their upper bodies and instead wear a shirt.

The first theme that emerges from this plea is that the Thai Sisters were required to modernize their bodies to modernize the nation. Though the regime did not overtly pursue siwilai as did the Siamese Kings, the path toward nation building laid out for women in the plea was similar to the one taken by Rama IV and his successors. Nation building for the newly minted Thailand was still a corporeal task, to be done on and to the body, but this time focused on the bodies of women.10) Modernity remained an individual responsibility that was concurrently a public performance to be consumed by and for the benefit of others.

The plea demanded that women become Thai by physically modifying their bodies (by growing out their hair) and modifying the ways their bodies were displayed (by changing the modes of dress). Nation building and patriotism in this context was a public display and performance for the Thai sisterhood. When the plea was issued, many women in the kingdom—such as those from the Lanna/Lao, Burmese, Malay, and Chinese communities—already wore their hair long, covered their upper bodies, and wore traditional wrap skirts (with the exception of Chinese women, who wore trousers). Indeed, wearing a wrap skirt and having long hair were salient visual markers of non-Siamese women just a few decades earlier (McIntosh 2000; Woodhouse 2012).

A second theme shows modernity to be a synthesis of tradition and innovation, the new and the old. As E. Reynolds (2004, 100–101) shows, the Phibunsongkhram regime, like other contemporary nationalist political movements of that era, aimed to build a new and idealized national identity that was deeply rooted in a glorified (imagined) past and to create a new nation from a cultural palimpsest of past empires. Imagined linkages to the past as part of nation building were not unique to Thailand or the Phibunsongkhram regime. Four years earlier in Italy, Benito Mussolini had added the phrase “Founder of the Empire” (Fondatore dell’Impero) to his official title, linking his fascist regime to the Roman Empire. Adolf Hitler, likewise, positioned his regime, the Third Reich, as the imperial successor to the Holy Roman Empire and the German Empire when he became chancellor in 1933. In March 1939, the Phibunsongkhram regime’s ideologue Luang Witchit Watthakan delivered a radio speech titled “Sukhothai Culture” that tethered the soon-to-be Thailand and Thainess to an idealized ancient kingdom. Modern Thainess as encoded in the Second Plea was a new fashion variation on a traditional theme.

Less than two weeks after the prime minister’s plea was issued, Chiwit Thai (Thai Life) magazine reprinted an illustration from a book titled Building Oneself (Fig. 1). The book contains useful pictures to show appropriate (modern and civilized) and inappropriate (backward and uncivilized) behavior in both the private and public spheres. Building oneself, after all, was to be done publicly at an individual level and encompassed all dimensions of daily life. Large letters above the illustration read “Is this still fine?” and the picture shows a woman hanging laundry by the roadside with the following caption:

Fig. 1 A Picture from a Book Titled Building Oneself, Reprinted in Chiwit Thai (March 26, 1941)

Our land is developed and prosperous. Even the streets are large and wide. If hang-drying clothes on the roadside is fine, if baring your chest is fine, will you ever realize that this sight is weighing down progress?

The woman pictured sports a traditional cropped hairstyle, is bare-chested, and wears the recently prohibited chong kraben pantaloons. This Thai Sister clearly did not heed the prime minister’s plea.

Interestingly, the laundry she is hanging comprises a pair of modern male trousers, complete with a zipper closure and belt loops, and a collared shirt. Her house has a Western-style picket fence, yet the woman is portrayed as being stuck in the past. A man wearing a modern-style shirt, trousers, and shoes walks on the other side of the street, holding a flat, rectangular portfolio that indexes his modern literacy. Passers-by look on from a Volkswagen Beetle. The choice of a German vehicle here is significant. The picture was reprinted in the magazine after Nazi Germany launched a successful attack on Yugoslavia and can be interpreted as a nod to Germany’s rising power and the importance of how Thailand was to be seen by the Third Reich.11) The message for the Thai Sister here is clear: she must improve herself for the nation and keep in step with the West, lest she be left behind as deadweight while others pass her by.

Phibunsongkhram’s plea, in summary, asks the Thai Sisters to embody a modern Thai womanhood through the implementation of Mandate 10. Modern Thainess as conceptualized in the plea did not contradict or exist in opposition to the future or the past. Thai Sisters could be modern in a way that was both traditionally Thai and fashionably modern by following the demand of the plea. Through this text, the regime conscripted women to fulfill a nationalist program, one in which they must build the nation with their bodies. The plea presents a cultural binary whereby the two pathways to modernity and patriotism exist together and not in opposition, an idea that would continue to reverberate in future messages to Thai Sisters. According to the plea, the only unacceptable choice would be for a Thai Sister to continue as before, without improvement and without change.

The Nation Child and Private Patriotism

Patriotism and nation building are never restricted to the public lives of citizens. This section will offer examples of how nationalism was internalized into the private lives of Thai Sisters through the appropriation of motherhood for nation building. A. Tansman (2009) shows that despite the Japanese government’s pervasive and persistent penetration into the private lives of Japanese citizens, there remained an “interiority” the regime was unable to conquer. But once nationalism was internalized by individuals, it surreptitiously seeped into the aesthetics of national culture in ways that were undetectable, even to those who publicly resisted against propaganda. These private moments of patriotism and internalized nationalism are what crafted the cultural tapestry that served as the backdrop for pre-World War II Japanese nation building. Though Tansman’s study was not gendered, the concept of “private patriotism” is useful in the analysis of the Thai Sisters propaganda texts.

Meanwhile, in Italy and Germany the two governments had already taken measures to expand nation building into citizens’ private spheres. The fascist and Nazi regimes, through various policies, gradually unraveled the public lives of women until their participation in nation building was restricted to the private confines of home, while simultaneously redrawing the boundaries of womanhood to comprise only two roles, wife and mother. In this way, Italian and German women were forced to internalize nationalism and perform patriotism and citizenry in private as individuals, while men’s participation was expected to be public (De Grazia 1992; Guenther 2004, 92–93).

In 1941 Thailand, the Phibunsongkhram regime was just beginning its advance into the interiority of the Thai Sisters’ lives. Three months after the First Plea on June 15, 1941, the premier addressed women for the second time with “The Prime Minister’s Plea for Our Thai Sisters, Titled ‘Wearing Hats.’”12) The speech added hats to the prescribed patriotic uniform in addition to the long hair, skirts, and covered torsos. The Second Plea is significantly longer than the first and is its ideological counterpart, the content dedicated to espousing the moral duty of citizens. The discourse is more formal than the First Plea and addresses the female audience as “All Esteemed Thai Sisters” (phi nong satri thai thi nap thue thang lai).

The Second Plea begins as a dialogue between Phibunsongkhram and the Esteemed Thai Sisters on the definition of a nation and the need for nation building. Between the lines, the text shows that there were nation-building skeptics with whom Phibunsongkhram wanted to directly engage (paragraphs 2–3). Here, the prime minister reaffirms that women must take responsibility for nation building in very concrete and personal ways. Whereas the First Plea mandated a patriotic uniform, the Second Plea situates All Esteemed Thai Sisters as mothers who have a duty to nurture and care for their child-nation:

[Nation building] is the same as when we have a child. You all try to mold and educate your child so that they become better. Few would allow their child to be illiterate, starve, or get sick. Whatever you would do for your child is what you must do for Nation Building. (paragraph 3)

The regime achieved two tasks with the Second Plea. First, the text situates nation building within the private, moral lives of women as mothers. Nation building in the First Plea was material, external, and public, something that could be acquired and performed to and with others. But in this Second Plea, the task of nation building becomes an internal, individual, and private act to be done in the home. By equating the tasks and responsibilities of nation building with those of motherhood, the regime superimposes patriotic expectations onto women’s most salient social role, one that carries moral, emotional, and biological weight.13) Patriotism via motherhood, in this context, becomes a natural part of idealized womanhood and a communal yet private activity on a national scale for the benefit of the mother (woman) and child (nation).

Motherhood as nation building was not restricted solely to ideology. The regime expected the Thai Sisters to also build the nation by producing more citizens. Whereas the perpetuation of the Siamese kingdom was embodied by the King and his many children, the virility of the Thai nation in 1941 could not rest on the teenage body of Rama VIII, who was only 14 when Phibunsongkhram came into power. Women and their bodies were now responsible for the proliferation of the Thai nation and the Thai people. The nationalization of women’s wombs culminated in the creation of prizes rewarding mothers for the number of children they had and the subsequent creation of Thai Mother’s Day in 1943.14)

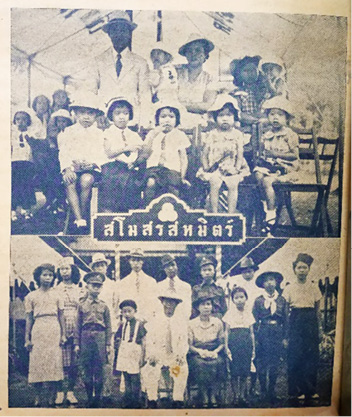

On October 13, 1941, a photo spread in Tai Mai or “New Tai” magazine featured two women, Wanphen Chuayprasit and Soi Limthongkhaw, who received prizes for having the highest number of children (Fig. 2). Wanphen (top), a mother of 8, was rewarded for having the most children born since 1932, while Soi (bottom), a mother of 12, was rewarded for having the most children in a category with no time limit. The two mothers are photographed with their husbands and children, who are dressed in accordance with Mandate 10 and the prime minister’s two pleas, complete with hats. Wanphen and Soi received their prizes at Amphon Park on October 4, 1941 at an event under the patronage of La-iad Phibunsongkhram, the prime minister’s wife and the mother of his six children.15) The picture of Wanphen and Soi, shown to be compliant in their Western clothes and prolific in their motherhood, presents them as exemplary Thai Sisters for the new nation.

Fig. 2 The Two Winners of Motherhood Prizes (Tai Mai, October 13, 1941)

Besides elevating hat-wearing mothers as the ideal woman, the Second Plea also reaffirms the corporeality of the Thai nation on women’s bodies. The Second Plea defines the term “nation building” (sang chat) as having three sequential components and uses lexical similarities to draw ideological parallels between the task of nation building (sang chat) and self-improvement (sang tong eng). Any improvements made to the self, as was the case for Siamese Kings of yesteryears, would be for the sake of the nation. But in this context, self-improvement could not be achieved by a Thai Sister without self-sacrifice because the child-nation was an extension of her own body.

The first step toward nation building was for the Thai Sisters to improve themselves to befit the prestige of their great nation. Self-improvement consisted of (1) maintaining one’s health by “nourishing yourself so that you are strong [and] free of sickness and disease”; (2) adjusting one’s behavior; (3) dressing “properly and appropriately, in the same manner as in other civilized nations”; (4) diligently working in one’s occupation; (5) diligently learning and seeking new knowledge; and (6) “diligently following the government’s suggestions for self-improvement and persevering until you have succeeded in every way” (paragraph 4). At around the same time, the regime also began a morning exercise radio broadcast, and magazines such as Chiwit Thai and Tai Mai began featuring exercises in their women’s columns (Fig. 3) (Kongsakon 2002).

Fig. 3 The Cover of Tai Mai Magazine Showing a Woman Exercising Along with the Daily Radio Broadcast (September 1, 1941)

Nation building through self-improvement now required physical changes to the bodies of women in the form of good nutrition and exercise, in addition to the prescribed dress code. As the “returned” territories of French Indochina restored the imagined integrity of the geo-body of Thailand, the newly prescribed patriotic uniform and modern Thai lifestyle would improve and make whole the bodies of the Thai Sisters.16) Those who did not comply would be morally and physically unfit and, therefore, deadweight for the Thai nation. Nation building through self-improvement in this era was no longer reserved for Siamese monarchs wishing to gain entry into modernity but was deemed a moral imperative for all Thai citizens. Even leisurely activities would later be categorized under the umbrella of self-improvement in Mandate 11.17)

The second step toward nation building was for the Thai Sisters to improve their families. Successful self-improvement was required for nation building, as this second task could begin only once the women had already improved themselves as prescribed. In comparison to the first requirement, the second was reasonably straightforward. To improve the family, the Thai Sisters had to be frugal, find some unused land to make a home, take care of this home, and educate their children. The third and final step asked that women extend their contribution to the common good beyond their homes. These three components of nation building, if efficaciously executed by the Thai Sisters, would help the nation prepare for “imminent conflict with powerful nations” (paragraph 5).

The Second Plea defines, in both concrete and ideological terms, the duties of citizens. The regime presented self-improvement as the heart of modern Thai citizenry. Nation building was defined as voluntary, cooperative, and deeply personal sacrifices, something internal and private for women as individuals. Within this context, nation building entered the realm of women’s personal lives and homes. Thai Sisters were now required to devoutly fulfill their prescribed roles as mothers to the Thai child-nation and proliferate the Thai family/race. This sense of private nationalism was to complement the outward application of these concepts on women’s bodies as the visual representation of progress and civility.

Patriotism as Fashion

Fashion has always been a political tool, as evidenced by the ways in which fin de siècle Siamese monarchs used modes of dress and Western accoutrements to perform modernity. This section will show how the world of fashion aided the construction of nationalistic ideals and the internalization of patriotism of the Thai Sisters more effectively than government policies. R. L. Blaszczyk (2009, 10) defines fashion, even in its most benign interpretation, as “a cultural phenomenon growing out of the interactions of individuals and institutions.” She further categorizes producers of fashion into two groups: tastemakers and intermediaries (ibid., 6). Together, these two groups are the ones who are responsible for suspending fashion in “the gel of culture,” and in the case of 1941 Thailand the culture was nation building. Whereas fashion tastemakers aim to create and pilot trends, generally producing top-down effects on the fashion world, fashion intermediaries manage the necessary interactions between consumers and those who sell fashion. Under this framework, it is the intermediaries—the popular press and women who make and sell fashion—who have the most impact, despite being largely uncredited for their work in the fashion world (ibid.). Fashion, under this definition, is a process and a system that is the product of individuals, institutions (including the individuals who make up the institutions), and culture.

Nation building as a fashion, then, goes beyond government policies and propaganda and is not the sole responsibility of any one entity. The Phibunsongkhram regime, together with fashion tastemakers and intermediaries, constructed the fashionably patriotic Thai woman. Popular media, in even more insidious ways than public policies, contributed to the interweaving of nationalism into the world of fashion. So when the prime minister acquiesced in his Second Plea by saying “I defer to all the Thai Sisters to please consider what is internationally fashionable,” the regime was yielding to the fashion tastemakers and intermediaries (paragraph 11). In the hands of elite Thai women (tastemakers) and magazine editors and writers (intermediaries), patriotism and nationalism quietly entered into the daily beauty regimen of the Thai Sisters and became fodder for female social interactions. The regime was very specific about how women were to put Mandate 10 into practice with the prime minister’s two pleas, but seemingly it did not receive the desired level of public cooperation.

Months after the issuance of Mandate 10, the regime continued to struggle with a lack of public compliance despite its multilateral efforts to promote the new dress code. Softer measures intended to publicly encourage compliance on all levels of society, such as clothing pageants, fashion flea markets, hat-making workshops, and making the new dress code a requisite for entry into events at Amphon Park, had failed. The Thai Sisters had not internalized patriotism and nation building, and nationalism stubbornly remained on the exterior and in public.

During a parliamentary meeting on September 6, 1941, four days after the last of the Thai Sisters texts, the regime tightened enforcement and issued a resolution to “maintain the sanctity of the Cultural Mandates” (Publicity Department 1941, 170–171). The resolution stated that those who were not dressed in accordance with Mandate 10 would not be allowed to enter government buildings and other public places, would not receive services from government agencies, and would not be allowed to use public transportation. The resolution concluded with a request for private businesses to cooperate with the government by putting in place similar restrictions. In all the ways that the regime had, thus far, failed to make patriotism a daily routine for the Thai Sisters, the world of fashion would succeed.

Hats were not new in Thailand. Neither were the various ways of wearing a hat. But, nevertheless, the Thai Sisters were seemingly resistant to the idea and struggled with how to wear hats in a “modern” and “civilized” manner. The innovation of wearing decorative hats (as opposed to functional work hats) seemed difficult to reconcile as part of the existing cultural praxis, and confusion and resistance continued well into 1941. That is why, perhaps, much of the public discussion on dress code, whether initiated by the regime or by the mass media, was dedicated to the ways hats and hat wearing fitted into the new schema of Thainess. Amon, throughout her radio address in September 1941, had to placate traditionalists and disabuse them of the notion that wearing hats would transgress Thai cultural norms:

There have been problems and confusion regarding how to pay respects when wearing hats. Some people misunderstood that when wearing hats, we cannot pay respects or prostrate as customary because hats are European. [The Council on the Guidelines for Women’s Dress] firmly believes that the use of international customs must not be a reason for abandoning the great Thai culture and behavior. The use of hats also must not cause us to abandon our manners and etiquette (khwam suphap riap roi). (Guidelines, part 2, paragraph 9)

Ensee Intharayothin, the head of the Office of Consumer Welfare, took to the airwaves twice to appeal to the Esteemed Ladies Everywhere. Ensee delivered his first treatise on millinery matters, appropriately titled “Ways of Wearing Hats,” on June 19, 1941.18) The speech provided excruciating details on hat-wearing history, fashion, and etiquette; and to conclude, Ensee pleaded for women to “help each other think, help each other improve, as a way to promote our culture in [the hat-wearing] method of nation building” (last paragraph).

Ensee’s concluding remark recruited the Thai Sisters to be benevolent gatekeepers of the patriotic uniform. The speech, in effect, deputized all who participated in the world of fashion as potential enforcers of patriotism and nationalized the self-policing of women’s bodies and self-presentation as a form of nation building. Moreover, the task of self-policing was framed as a way for the Thai Sisters to improve themselves and help other women, reiterating the need for women to make physical changes to their bodies for the nation. The policing of women’s bodies prior to 1932 applied only to upper-class women whose self-presentation, lineage, and matrimonial linkages were scrutinized and carefully curated. Women with no rank generally had freedom in choosing their spouse and their manner of dress (Loos 2004).

Ensee’s speech was not well received as he returned to the airwaves 10 days later with an elaborate apology to the Esteemed Ladies for his hubris. The pushback must have been severe to require such verbal groveling:

I did not intend to teach you about the beauty of hats because with these things, you must already know better than me what is beautiful. You are a woman. . . . I leave that to be your responsibility to consider and decide or find out from women circles. The Department of Public Welfare did not intend to regulate the occasion in which you should wear hats . . . Who will dare nitpick and bother you, making this rule and that rule? (paragraph 2)

Despite the deferential tone, Ensee nevertheless demanded that the Esteemed Ladies enforce dress code compliance among themselves. Not only that, the patriotic uniform, hat and all, was presented in this speech as fashionable and a standard of beauty in the context of nation building. Phibunsongkhram had earlier hinted at the idea of patriotism as beauty in the Second Plea when he added hats to the patriotic uniform: “I speak of the wearing of hats as your duty in Nation Building, so that Thai women will shine more brightly” (paragraph 11).

Patriotism as part of women’s beauty regimen was further promoted by the various clothing pageants held throughout the country. The regime also reimagined the Miss Siam pageant as the Miss Thailand pageant, in which elite young women competed to be the feminine and fashionable ideals of a new nation. The reigning Miss Thailand (1941), Sawangchit Kharuehanon, and the first ever Miss Thailand (1940), Mariam (Riam) Phesayanawin, regularly graced magazine covers and made public appearances, fulfilling their role as patriotic tastemakers. Fashion intermediaries reported on their public appearances and other stylishly patriotic society events within the pages of popular magazines such as Tai Mai and Chiwit Thai, helping to usher nationalism deep into the world of fashion. Even newspapers that were once deemed radical, such as Srikrung (Glorious City), became fashion intermediaries for the patriotic dress code. The cover of the March 23, 1941 issue shows a picture of Thais dressed in compliance with Mandate 10 (Fig. 4). The caption reads, “National progress rests on culture; thus, the mode of dress is important. We, the people, must comply with the Prime Minister’s plea for the sake of national progress and our own self-improvement.”

Fig. 4 The Cover of Srikrung Newspaper Promoting the Dress Code Prescribed by Mandate 10 (March 23, 1941)

The August 13, 1941 issue of Chiwit Thai magazine prominently featured a human-interest piece about a charity flea market held at Amphon Park on August 3.19) In the article the Publicity Department, one of the co-sponsors of the event, described it as “one of the biggest hat-wearing events for all to witness.” The all-day event featured a group demonstration of the daily radio broadcast morning exercises at 6 a.m. and a clothing and hat pageant competition shortly after 8 a.m. The first prize winner of the junior category, Somprasoet Suphrangkun, received one of La-iad Phibunsongkhram’s 24-karat gold bracelets.

Patriotism, as a stowaway in fashion, slipped into all areas of women’s private lives, abetted by the work of fashion tastemakers and intermediaries. Mandate 5 had dictated earlier that

Thais should try to consume only food prepared from products which originate or are produced in Thailand; try to dress with materials which originate or are produced in Thailand; should help to support indigenous agricultural, commercial, and industrial occupations and professions. (Thak et al. 1978, 248)

The Thai fashion industry in 1941, which was nascent at best, was not ready for the new patriotic dress code. As a result, the Thai Sisters had to rely on foreign-made items to comply with Mandate 10.

The regime, realizing its mistake, scrambled to organize a series of millinery workshops for women, transmogrifying the acquisition of basic vocational skills into a patriotic duty and blurring the lines between fashion consumers and producers. Between September 8 and November 27, the Department of Public Welfare and the Office of Consumer Welfare co-hosted a series of millinery workshops for women at the National Commercial Building. Sa-nga (formerly Amelia) Sukhabut, a Westerner married into the prestigious Sukhabut law family, instructed the attendees with the help of an interpreter (Fig. 5). Being a stylish Western woman herself, Sa-nga was the perfect candidate to preach the millinery gospel to Thai proselytes. Participants could show off their handiwork immediately at the gala dinners the Department of Public Welfare organized to complement the workshops. Two participants even modeled their self-made hats on the cover of the October 20 issue of Tai Mai. Amon, the sole female signatory of the Thai Sisters text, may have been one of the attendees, as she later opened an eponymous hat boutique named Ran Amon on Ratchadamnoen Road.

Fig. 5 Millinery Workshop Hosted by the Department of Public Welfare (Tai Mai, September 15, 1941)

Eventually, anyone in any trade could participate in fashionable patriotism. Newly founded schools filled the advertisement pages with hat- and Western clothes-making classes. Tailors and seamstresses clambered to attract buyers for their “Thai-made” fashionable wares. Products otherwise unrelated to clothing injected patriotism into their advertisements to promote their goods as the perfect complement to a fashionably patriotic woman. The advertisement for Chula Brand soap, for example, compared the newly improved bar soap with the newly improved Thai ladies who were dressed “appropriately for our civilized times” (Fig. 6). The regime continued to host the increasingly popular “Thai-made” flea markets at Amphon Park.

Fig. 6 Advertisement for Chula Brand Soap (Tai Mai, January 6, 1941)

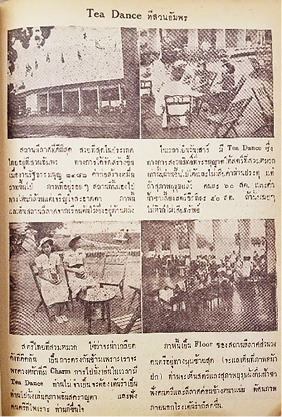

This is not to say that all Thai women were compliant and cooperative with the demands of the regime. Samples of print media during this time suggest that some Thai Sisters remained skeptical of the patriotic dress code, though direct evidence of public opposition to Mandate 10 is elusive amidst state-controlled media. The regime had already shut the doors of women’s magazines that mobilized women to fulfill roles beyond mothers and wives, because they were deemed “too political” by the time Mandate 10 was issued (Ubolwan and Uaypon 1989, 25). Careful examination, however, shows that some Thai Sisters continued to ignore the bombardment of propaganda urging compliance with the dress code. In the July 9, 1941 issue of Chiwit Thai, a photo spread hints at an atmosphere of opposition against hats (Fig. 7). The photos show women who attended a tea dance held at Amphon Park on July 5. One caption states that only hat-wearing women were allowed entry into the event (top right), while another caption reads “Hat-wearing ladies. See, it’s not as unsightly as you thought! We think it’s the opposite, based on the charm exuding from their faces” (bottom left).

Fig. 7 A Photo Spread in Chiwit Thai That Hints at Women’s Resistance to Wearing Hats (July 9, 1941)

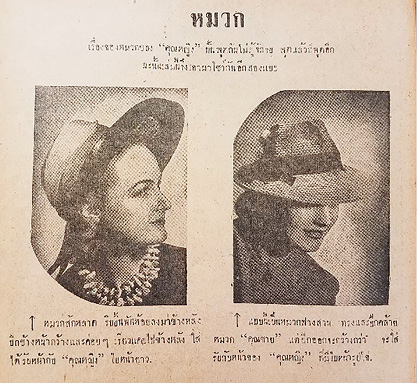

By the October 8, 1941 issue, even a magazine like Chiwit Thai, which unabashedly supported the regime, was weary of publishing pro-hat messages. The magazine regularly ran a section named “The Ladies” (khun ying) that offered tips on how women could keep up with the latest fashion in the constitutional age. Here, women could find the latest recipes, hairstyles, clothing and shoe designs, and tips on how to manage their household, all important aspects of the newly constructed modern Thai woman. The October 8 edition of “The Ladies” on page 34 reads, “Hats for ‘The Ladies’ is a never-ending conversation. Over and over, it happens. So we are showing two more types [of hats] in this issue” (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 The October 8, 1941 Edition of “The Ladies” (Chiwit Thai Magazine)

One can also read between the lines of the numerous Thai Sisters texts that, overall, the Ladies Everywhere, esteemed or otherwise, continued to be ambivalent or altogether noncompliant despite the great efforts to propagandize them into submission. It remains unclear how the regime was able to effectively enforce Mandate 10, beyond the stern measures of the seemingly desperate parliamentary resolution of September 1941. It is also unknown what legal consequences, besides denial of service, the Thai Sisters faced if they did not comply. Had the regime not struggled with public compliance, there would be no need for the resolution or the onslaught of propaganda.

Patriotism and nationalism had become a part of the Thai Sisters’ daily life and fashion routine, thanks in part to the work of fashion intermediaries as defined by Blaszczyk (2009). By the time Thailand entered World War II the following year, the media and regime had turned their attention away from the patriotic dress code. Compliance with Mandate 10 had either largely been met, or the regime refocused its propagandic energy toward grooming the citizens for war. There is not yet any definitive proof that the regime designed the Cultural Mandates to accelerate the development of the Thai fashion industry, though it must have claimed responsibility for the production and economic boom that came as a result. Rightly so: without Mandate 10, there would have been no need for businesses to meet the demands of women needing to style newly long hair, wear Western-style clothes and shoes, and exercise daily.

IV Conclusion

Embodying modernity and nationality was a self-improvement task for fin de siècle Siamese monarchs. In that process, their bodies along with their visual representations were iconized as sites for the modernization of Siam (Peleggi 2002; 2007). The lack of a kingly body resulting from the abdication of Rama VII and the physical absence of his successor, the child-king Rama VIII, made modernity and nation building necessarily a civilian task when Phibunsongkhram came into power in 1938. With the issuance of Mandate 10 and the supplemental texts examined in the above sections, the regime relocated the physical locus of modernization and nation building onto the bodies of women, effectively abandoning royal bodies. The Thai Sisters were, thus, conscripted to be corporeal proxies for the nation in place of the monarchs, and their bodies were transformed into public sites for the performance of patriotic propaganda.

Nation building, however, occurred also at a private and individual level. For the sake of the nation, citizens were asked to submit to the patriotic appropriation of their private lives so that the nation became internalized and naturalized within themselves (Tansman 2009). This sense of private nationalism was promoted in the supplemental texts, wherein the regime linked women’s nation-building tasks to those of a mother. By framing nation building as analogous to the biological and emotional experiences of a mother, the regime sought to place patriotism into the private lives of Thai women. Repeated lexical parallels in the supplemental texts further equated nation building (saang chaat) with self-improvement (saang ton eeng), so that in order to modernize the nation the Thai Sisters had to first modernize their bodies.

Such vestimentary nation building turned popular magazines such as Tai Mai and Chiwit Thai into patriotic battlegrounds for those whom Blaszczyk (2009) calls fashion intermediaries and tastemakers. In the realm of fashion, enforcement could come in the form of photo spreads and beauty pageants. Any Thai Sister could now be a gatekeeper and arbiter of patriotism in her own home and social circle. Nation building and modernization by way of self-improvement were literally sewn into clothes, learned as vocations, modeled on beauty queens, and advertised in magazines.

Mandate 10 and its supplemental texts to the Thai Sisters demanded that the feminine body physically bear the burden of nation building. The creation of a detailed patriotic dress code for women relocated nation building away from the male bodies of monarchs and onto the bodies of Thai women. And by weaving nation building into women’s private lives, the Phibunsongkhram regime made the (self-)policing of women’s bodies—formerly restricted to elite women—not only essential but also fashionable and patriotic for all Thai Sisters.

Accepted: February 19, 2019

References

Barmé, Scot. 2002. Woman, Man, Bangkok: Love, Sex & Popular Culture in Thailand. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Blaszczyk, Regina Lee. 2009. Rethinking Fashion. In Producing Fashion: Commerce, Culture, and Consumers, edited by Regina Lee Blaszczyk, pp. 1–18. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Conway, Susan. 2002. Hither Come the Merchants: Textiles Trade at the 19th Century Courts of Lan Na (North Thailand), Chiang Tung (Eastern Shan States), Lan Xang (Western Laos) and Sipsong Pan Na (Xinshuang Banna, South-west China). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. Lincoln: Textile Society of America. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1376&context=tsaconf, accessed November 5, 2018.

Davisakd Puaksom. 2007. Of Germs, Public Hygiene, and the Healthy Body: The Making of the Medicalizing State in Thailand. The Journal of Asian Studies 66(2): 311–344. doi:10.1017/S0021911807000599.

de Baecque, Anthoine. 1993. The Body Politic: Corporeal Metaphor in Revolutionary France, 1770–1800. Translated by Charlotte Mandell. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

de Grazia, Victoria. 1992. How Fascism Ruled Women: Italy, 1922–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dhamma Thai. http://www.dhammathai.org/watthai/bangkok/watphrasrimahathat.php, accessed November 5, 2018.

Durham, Martin. 1998. Women and Fascism. New York: Routledge.

Edwards, Penny. 2001. Restyling Colonial Cambodia (1860–1954): French Dressing, Indigenous Custom and National Costume. Fashion Theory 5(4): 389–416.

Gray, Christine E. 1991. Hegemonic Images: Language and Silence in the Royal Thai Polity. Man, New Series 26(1): 43–65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2803474.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Af27043180a170d8bdd4edcb9f6b1e0b6, accessed November 5, 2018.

Guenther, Irene. 2004. Nazi Chic? Fashioning Women in the Third Reich. New York: Berg.

Ikeya, Chie. 2011. Refiguring Women, Colonialism, and Modernity in Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Jackson, Peter. 2003. Performative Genders, Perverse Desires: A Bio-History of Thailand’s Same-sex and Transgender Cultures. Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context (9): 43. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue9/jackson.html, accessed January 8, 2016.

Kantorowicz, Ernst H. 1997. The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. Princeton: Princetone University Press.

Kongsakon Kawinraweekun ก้องสกล กวินรวีกุล. 2002. Kansang rangkai phonlamueng thai nai samai chomphon po. phibunsongkhram pho. so. 2481–2487 การสร้างร่างกายพลเมืองไทยในสมัยจอมพล ป. พิบูลสงคราม พ.ศ. 2481–2487 [Constructing the body of Thai citizens during the Phibun Regime of 1938–1944]. Faculty of Social Science and Humanities, Thammasat University.

Loos, Tamara. 2004. The Politics of Women’s Suffrage in Thailand. In Women’s Suffrage in Asia: Gender, Nationalism and Democracy, edited by Louise Edwards and Mina Roces, pp. 170–194. New York: RoutledgeCurzon.

McIntosh, Linda. 2000. Thai Textiles: The Changing Roles of Ethnic Textiles in Thailand. Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, pp. 402–408. Lincoln: Textile Society of America. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1823&context=tsaconf, accessed November 5, 2018.

Nanthira Khamphiban นันทิรา ขำภิบาล. 1987. Nayobai kiaokap phuying thai nai samai sangchat khong chomphon po. Phibunsongkhram pho. so. 2481–2487 นโยบายเกี่ยวกับผู้หญิงไทยในสมัยสร้างชาติของจอมพล ป.พิบูลสงคราม พ.ศ. 2481–2487 [Women policies during the nation building period of Field Marshall Phibunsongkhram, 1938–1944]. Faculty of Arts, Thammasat University.

Peleggi, Maurizio. 2007. Refashioning Civilization: Dress and Bodily Practice in Thai Nation-Building. In The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas, edited by Mina Roces and Louise Edwards, pp. 65–80. Portland: Sussex Academic Press.

―. 2002. Lord of Things: The Fashioning of the Siamese Monarchy’s Modern Image. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Piyawan Asawarachan ปิยวรรณ อัศวราชันย์. 2012. Khwamkhit khong phunam lae kitchakam khong ying thai nai samai songkhram lok khrang thi song ความคิดของผู้นำและกิจกรรมของหญิงไทยในสมัยสงครามโลกครั้งที่ 2 ภายใต้เงากองทัพญี่ปุ่น [The leadership’s perception towards Thai women during World War II under the influence of the Japanese military regime]. Japanese Studies Network Journal (JSN Journal) 2(1): 1–19. https://www.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jsn/article/view/42407/35053, accessed July 10, 2017.

Publicity Department กรมโฆษณาการ. 1941. Pramuan ratthaniyom lae rabiap watthanatham haeng chat, chabap thi song ประมวลรัฐนิยมและระเบียบวัฒนธรรมแห่งชาติ, ฉบับที่ ๒ [Collection of Mandates, Codes, and Guidelines for National Culture, 2nd edition]. Publicity Department. Bangkok, Thailand.

Reynolds, E. Bruce. 2004. Phibun Songkhram and Thai Nationalism in the Fascist Era. European Journal of East Asian Studies (Brill) 3(1): 99–134.

Royal Institute of Thailand ราชบัณฑิตยสถาน. 1999. Lakkan thot akson thai pen akson roman baep thai siang หลักเกณฑ์การถอดอักษรไทยเป็นอักษรโรมันแบบถ่ายเสียง [Guidelines for transliterating Thai into Roman script]. Royal Institute of Thailand.

Strate, Shane. 2015. The Lost Territories: Thailand’s History of National Humiliation. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Suksun Dangpakdee สุขสรรค์ แดงภักดี. 1994. Khwamwang khong sangkhom tho satri thai nai samai sangchat pho. so. 2481–2487 ความหวังของสังคมต่อสตรีไทยในสมัยสร้างชาติ พ.ศ. 2481–2487 [Society’s expectations of Thai women in the ‘Nation Building’ Period, 1938–1944]. Faculty of Arts, Chulalongkorn University.

Tansman, Alan. 2009. The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Thak Chaloemtiarana; Charnvit Kasetsiri; and Thinapan Nakhata. 1978. Thai Politics: Extracts and Documents, Vol. 1. Bangkok: Social Science Association of Thailand.

Thamsook Numnonda. 1978. Pibulsongkram’s Thai Nation-Building Programme during the Japanese Military Presence, 1941–1945. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (Japan and the Western Powers in Southeast Asia) 9(2): 234–247.

Ubolwan Pitipattanakosit อุบลวรรณ ปิติพัฒนะโฆษิต; and Uaypon Panit อวยพร พานิช. 1989. 100 Pi khong nittayasan satri thai pho. so. 2431–2531 100 ปีของนิตยสารสตรีไทย พ.ศ. 2431–2531 [100 years of women’s magazines (1888–1988)]. Faculty of Communication Arts, Chulalongkorn University.

Woodhouse, Leslie. 2012. Concubines with Cameras: Royal Siamese Consorts Picturing Femininity and Ethnic Difference in Early 20th Century Siam. Trans-Asia Photography Review 12(2). https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tap/7977573.0002.202?view=text;rgn=main, accessed September 14, 2018.

1) In Thai, “ประมวลรัฐนิยมและระเบียบวัฒนธรรมแห่งชาติ” (pramuan ratthaniyom lae rabiap watthanatham haeng chat).

2) Notable exceptions are works in Thai, namely, Piyawan Asawarachan’s “The Leadership’s Perception towards Thai Women during World War II under the Influence of the Japanese Military Regime” (2012) and two unpublished graduate theses, “Women Policies during the Nation Building Period of Field Marshall Phibunsongkhram, 1939–1945” by Nanthira Khamphiban (1987) and “Society’s Expectations of Thai Women in the ‘Nation Building’ Period, 1938–1944” by Suksun Dangpakdee (1994).

3) The interwar years are defined as the period between the end of the Great War in 1918 and the beginning of World War II in 1939. The interwar years were characterized by: (1) political, social, and emotional reactions to and recovery from the Great War; (2) the economic prosperity of the 1920s; and (3) the Great Depression.

4) Some military nationalist regimes that were in power during the interwar years were: Mussolini in Italy, Stalin in Russian, Franco in Spain, Hitler in Germany, Ataturk in Turkey, Chiang Kai-shek in China, and Hirohito in Japan.

5) Siamese and Thai Kings of House Chakri are commonly referred to by their chronological order of reign. The first Chakri King, King Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok, is thus Rama I, King Vajiravudh is Rama VI, and the current king of Thailand, King Vajiralongkorn, is Rama X.

6) Phanung (lit. “cloth for wearing”) is a rectangular piece of cloth wrapped around the lower body, the ends of which can be folded or rolled together in the front and then tucked between the legs to fashion it into a pantaloon called chong kraben. Every Siamese wore this piece of clothing, regardless of age, status, and gender.

7) The Thai name for the Cultural Mandates is Ratthaniyom, which translates to “state or national values.” This study follows the common practice of using “Cultural Mandates” to refer to the 12 mandates issued by the Phibunsongkhram regime between 1939 and 1942.

8) This is not to say that men were not subjected to the demands of Mandate 10 and its many subsequent expansions. Men also had newly prescribed modes of dress, and an exploration of the recruitment of men to nation building via fashion is a worthwhile future endeavor.

9) In Thai: คำวิงวอนของท่านนายกรัฐมตรี (ฝากไว้แก่พี่น้องสตรีไทย) Kham wingwon khong thaan nayok ratthamontrii (faak wai kae phii nong satrii thai)

10) Mandate 1 was issued on June 24, 1939 and states, “The name of the country is to be ‘Thailand’” (Thak et al. 1978, 245). Prior to the Cultural Mandates, the kingdom was officially called Siam.

11) The Phibunsongkhram regime borrowed heavily from contemporary nationalist military governments, specifically fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, and early Shōwa Japan. The extent and details of their influence are beyond the scope of this paper.

12) Title in Thai, คำวิงวอนของท่านนายกรัฐมนตรี แด่พี่น้องสตรีไทย เรื่อง การสวมหมวก (kham wingwon khong than nai yok ratthamontri dae phinong satri thai rueng kansuammuak).

13) The Phibunsongkhram regime was not at all original in its attempts to equate motherhood with nation building. Similar policies of contemporary nationalist regimes predate those in Thailand. Even then, the policies of fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, and early Shōwa Japan were merely twentieth-century reiterations of common ideologies of past empires.

14) A decade earlier, in 1933, fascist Italy and Nazi Germany both declared a national holiday, Giornata della Madre e dell’Infanzia and Muttertag respectively, in celebration of mothers and motherhood as part of their nation-building campaign.

15) The October 1943 issue of Wannakhadisan (Literary Magazine) was published in honor of La-iad’s birthday and, through prose and poetry, praised her as the ideal wife and mother. Phibunsongkhram wrote the introduction and dedication.

16) For a detailed discussion of the nation-building narrative surrounding the Franco-Thai War of 1940–41, see Shane Strate’s The Lost Territories: Thailand’s History of National Humiliation (2015). For an examination of the role of bodily health in Thai nation building, see Kongsakon Kawinraweekun’s “Constructing the Body of Thai Citizens during the Phibun Regime of 1938–1944” (2002) and Davisakd Puaksom’s “Of Germs, Public Hygiene, and the Healthy Body: The Making of the Medicalizing State in Thailand” (2007).

17) Issued on September 8, 1941, Mandate 11 states: “. . . the proper carrying out of daily activities is an important factor for the maintenance and promotion of national culture and hence the vigorous health of Thai citizens and their support for the country . . .” (Thak et al. 1978, 253). The mandate divides the day into three discrete eight-hour parts: work, sleep, and leisurely activities done for the sake of self-improvement (ibid.).

18) Title in Thai, ปาฐกถา เรื่อง การใช้หมวกสำหรับสตรีไทย (pathakatha rueng kan chai muak samrap satri thai).

19) Proceeds of the event went to the building of Phra Srimahathat Woramahawihan Temple. Phibunsongkhram proposed the building of a Democracy Temple (Wat Prachathippatai) near the site of the Fifth Constitution Monument, or Protected Constitution Monument (Anusaowaree Phithakrattathamanoon) in Thai, which was erected to celebrate the quelling of the Boraworadet Rebellion. The purposes of the temple were to: (1) celebrate National Day in 1941, (2) honor Buddhism as the national religion and the Buddhist principles guiding democracy, and (3) celebrate the change of political system from absolute monarchy to constitutional democracy (see Dhammathai website).